Everyone wants to do “what is right for the environment.” But what about when the proposed solution is worse than the supposed problem?

Wegmans, a regional supermarket chain with 107 stores, announced in April it is eliminating plastic shopping bags from all of its locations by the end of 2022. It plans to shift all customers to stitched-handle reusable bags instead. They are also made of plastic (polypropylene)—and usually imported from China, unlike single-use bags made in the U.S.—but Wegmans considers them “the best option to solve the environmental challenge of single-use grocery bags.”

“We understand shoppers are accustomed to receiving plastic bags at checkout and losing that option requires a significant change,” said Jason Wadsworth, Wegmans’ category merchant for packaging, energy, and sustainability in a press release. “We are here to help our customers with this transition as we focus on doing what is right for the environment.”

But in a December 2021 pre-enforcement meeting with the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), Wadsworth raised questions about the net impact of the new policy on the environment. (New Jersey banned plastic grocery bags beginning May 4, 2022.)

According to publicly-available transcripts of the meeting, Wadsworth noted that by completely ending the use of traditional plastic shopping bags or paper bags the grocery chain would be sending a steady supply of the stitched-handle bags via home delivery services like Instacart, which Wegmans uses for online food orders.

“We’re working on that and hopefully we’ll have a solution soon. But even whether it’s a recycling solution, just think about the bags (that) are manufactured using plastic, a thicker plastic.” And because reusable bags require so much more plastic to manufacture than traditional shopping bags, the net result could be more plastic in the supply chain, not less.

“So, if we just go by the principles of reduce, reuse, recycle, we are increasing the amount of material being used compared to a paper bag and that supply chain from China, which is where these bags are manufactured,” Wadsworth went on. “If you were just to use it once and recycle it, that becomes more problematic than a paper bag that gets recycled after one use, so just making those comparisons.”

Wadsworth’s words were prophetic. Just four months after New Jersey’s ban on single-use shopping bags was imposed, shoppers complain they are being buried under mounds of the larger, stitched-handle plastic bags.

“They may be reusable bags, but in too many cases they are only being used once,” said New Jersey state Sen. Michael Testa (R). “It is a waste of money that is burdening the state’s employers and piling on to product costs, compounding the impact of 8 percent inflation.”

Even one sponsor of the bag ban acknowledged the problem, which he dismissed as a “glitch.”

“The only glitch so far that we’ve had (during the ban) is the fact that the home delivery of groceries has been interpreted to mean you have to do it in a reusable bag, and what’s happening is the number of these bags are accumulating with customers,” state Sen. Bob Smith (D) told Staten Island Live. “We know it’s a problem. We agree it’s a problem.”

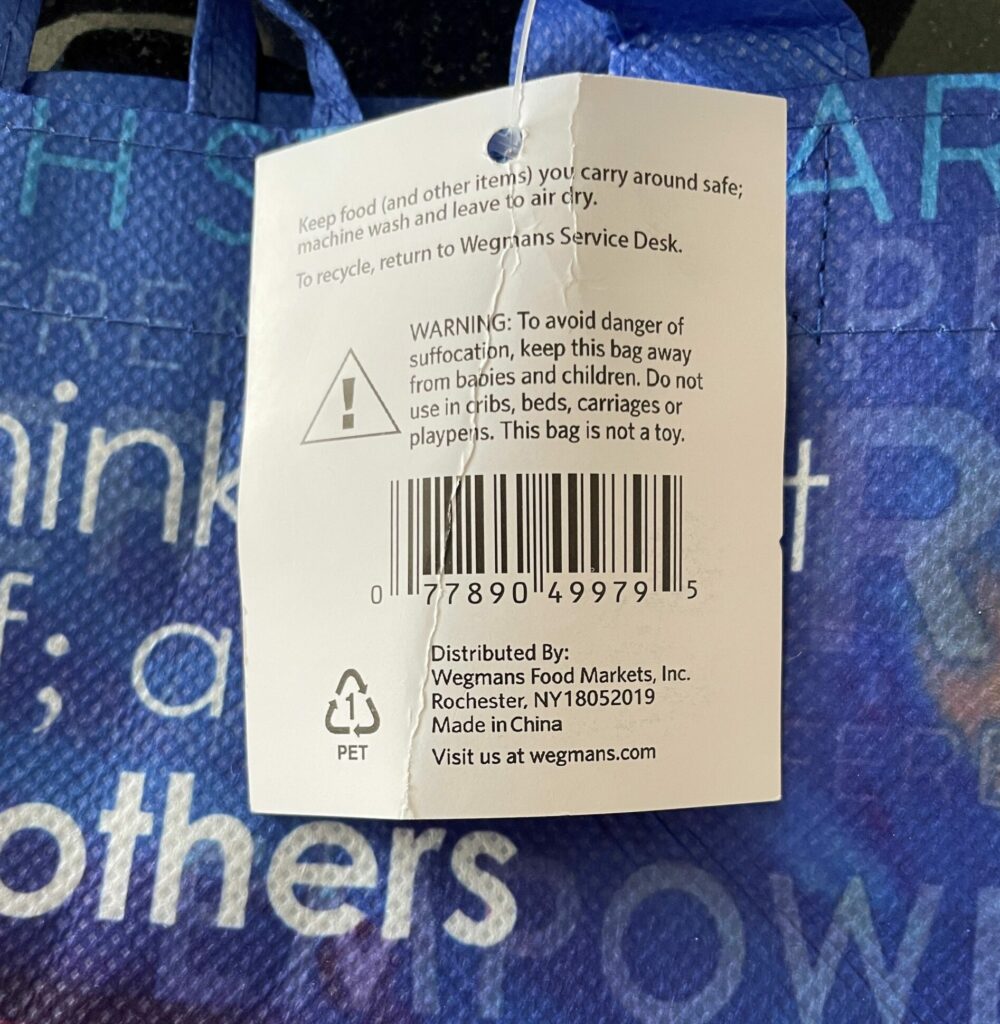

In the 2021 meeting, Wadsworth also pointed out that proponents of reusable bags were pushing recycling as a solution, but that was not feasible, either. While a tag on reusable bags from Wegmans instructs customers to return them to a Wegmans Service Desk for recycling purposes, “there is no mechanism to recycle these reusable bags,” he said.

In the 2021 meeting, Wadsworth also pointed out that proponents of reusable bags were pushing recycling as a solution, but that was not feasible, either. While a tag on reusable bags from Wegmans instructs customers to return them to a Wegmans Service Desk for recycling purposes, “there is no mechanism to recycle these reusable bags,” he said.

According to John Tierney, contributing editor at the City Journal, the entire conversation around stitched handle bags is off the scientific mark.

“They are worse for the environment, they are less healthy, and they are more expensive,” said Tierney.

A science writer known for New York Times articles including “Recycling is garbage,” Tierney considers the single-use plastic bag a miracle of economic and environmental efficiency.

“It takes very little energy to create it, transport it, takes up little room in landfills and these multiple-use plastic bags involve a lot more greenhouse gas emissions because it takes more energy to make them and to transport them and people do not use them often enough to offset those extra greenhouse gas emissions,” Tierney added. “By banning single-use plastic bags, you are actually increasing carbon emissions and you’re inconveniencing people.”

And, said Testa, you are costing New Jersey jobs by importing the bags from China instead of buying local.

“These imported carriers, specifically allowed by the current law, are all manufactured overseas, and they cannot be recycled in the U.S. This is what happens when legislation is rushed through and proponents refuse to listen to reason,” Testa pointed out. “The restriction should have been designed to utilize bags made in America and recyclable in America. It is more important to get things done right than it is to get it done fast.”

Julian Morris, senior fellow for Reason Foundation and author of “How Green Is That Grocery Bag?” also says the common plastic bags being replaced are the better option for people and the planet.

“You’re moving a heavier, oil-derived bag or cloth bag thousands of miles in order to get it to the United States, whereas the ones that are produced here are made from natural gas,” Morris said.

As for the issue of plastic bags being found in streets and other areas, Morris said that is an indicator that littering is a problem that should be addressed.

“It could be the sanitation department not doing its job or the public could be doing more to litter less,” said Morris. “Try to encourage your citizens to behave better and also maybe engage in cleanup campaigns as well as your sanitation department doing its job properly.”

All things considered, Tierney said, banning plastic bags is nothing but virtue signaling that is bad for the environment and bad for the consumers.

Please follow DVJournal on social media: Twitter@DVJournal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJournal