This article first appeared in Broad & Liberty

Gerrymandering used to be an under-the-radar political fight, known mostly to insiders. In recent years, it has taken on new prominence as congressional and state legislative districts are rewritten every ten years — with the spoils going to the victors.

Pennsylvania’s most recent round is a case in point: despite losing the statewide vote by 379,000, Democrats control the state house today because of lines forced through by the Democrat-controlled state Supreme Court.

The process goes on in miniature across the commonwealth, too. One such line-drawing fight is playing out in court right now in Upper Providence Township in Delaware County.

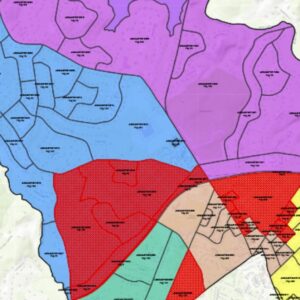

The township is governed by a board of five members, each elected in a single-member district. When the lines were last drawn 30 years ago, the districts were roughly equal. Now, minor population shifts have left some more populous than others. So, the township council shifted the lines to make the districts closer to equal in population.

Everyone agrees that the districts are now more equal in size, but the way they got there — and which neighborhoods were put where — is a more contentious topic. Some Upper Providence residents allege that the lines are unnecessarily disruptive and were drawn to protect a Democratic majority on the board. The board, through court documents, denies this is the case.

Just shy of 40 percent of the township is Republican, but four of five members of the township council are Democrats. The residents opposing the changed borders say that the changes “shifted the partisan balance of the Township strongly in favor of the Majority party,” according to their website.

But wait a second — in the current registration analysis, Republicans only have an advantage in one district, and then that shifts to an advantage in two districts. How can this be a gerrymander?

“My ultimate contention is that right now, there are only two Dem ‘leaning’ districts. I know on paper there are four in their ‘column,’ but frankly, given voting trends and turnout rates, the D+5 and D+6 districts are extremely competitive toss-ups,” said Joe Solomon, one of the driving forces behind the website and lawsuit.

“What [the council is doing] is essentially sacrificing an advantage in one of the toss-ups (the 3rd District — albeit, it remains a toss-up) and by doing so they guarantee themselves another district in the 4th District,” Solomon continued.

“So the gerrymander is that, instead of having a 2–1 advantage in seats and competing for the other two with an advantage, they now guarantee a 3–1 Council, which is majority control. They no longer have to spend campaign resources in the 4th District and can reliably count on majority control of the Township for the foreseeable future,” he concluded.

Everyone agrees that the districts are now more equal in size, but the way they got there — and which neighborhoods were put where — is a more contentious topic.

The council declined to respond to Broad + Liberty’s request for comment, citing the pending lawsuit, but did include copies of their response to the charges, which they have filed with the courts.

“[I]n 2022, the Democrats won in all five districts decisively. Republicans cannot show that they lost narrowly anywhere. Republicans also did not have ‘wasted votes’ because they did not win any races,” the council’s reply brief says. “If anything, it shows Republicans are vastly overrepresented by the one seat they held on Township Council.”

Also in those filings, the council’s attorney notes that the challenges to the new lines ignore independent voters in their calculus while also pointing out that even under the old district lines, Democrats carried all five districts in the 2022 races for governor and United States senator.

At the heart of the dispute is the question of whether the boundaries chosen by the Democratic-majority council rise to the level of the standard in Pennsylvania’s gerrymandering caselaw, which the state supreme court in League of Women Voters v. Commonwealth describes as showing that the map “clearly, palpably, and plainly violates the Constitution.”

Defining exactly what that means is not easy. The Upper Providence case could be the first since League of Women Voters in 2018 to drill down on exactly how one could prove such a violation.