Americans were appalled when Hamas seized 240 hostages during its October 7 attack on Israel. Among the hostages were several Americans, and the White House says there are seven Americans — one woman and six men — still unaccounted for.

People old enough to remember the Iranian hostage crisis or the Patty Hearst story know the political kidnapping of Americans is nothing new.

Consider, for a moment, how Washington handled an international hostage crisis in 1904.

Of the many odd people who’ve wandered into American history, Ion Perdicaris was among the strangest. His father immigrated from Greece in the early 1800s and married into a wealthy South Carolina family. Then, he doubled his fortune by investing in gas works up North.

Perdicaris was born into the lap of luxury in 1842. When the Civil War began, he hopped on a ship to Athens, handed over his American passport, and became a Greek citizen, hoping that would spare his family’s Southern property from destruction.

He eventually settled in Tangier, Morocco. There, he built a mansion called the “Place of Nightingales” filled with exotic animals. He studied Moroccan culture (which he loved), partied, wrote books, frequently went to New York on business, and even seduced a married Englishwoman — who left her husband and settled into Perdicaris’ mansion with her four children.

Fast forward to 1904. Morocco was led by a 26-year-old sultan who ruled like a tyrant at the head of a corrupt government. To say Morocco was a mess was putting it mildly. Sensing vulnerability, Britain, France and Germany came sniffing around, hoping to expand their empires. Which is where Mulai Ahmed er Raisuli enters the story.

Raisuli was the 33-year-old leader of a tribal confederacy bent on overthrowing Morocco’s government. Part pirate and thief, part heroic revolutionary, he was a Robin Hood combination of good and bad rolled into one. But on May 18, 1904, he bit off more than he bargained for.

Raisuli’s men kidnapped Perdicaris and his stepson, demanding $70,000 in ransom (about $2.25 million today).

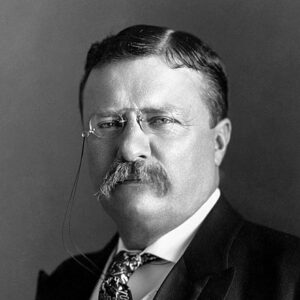

President Teddy Roosevelt went ballistic. How dare a terrorist kidnap and hold a U.S. citizen hostage! (Because Perdicaris was so well-known in New York and the South, it was mistakenly assumed he was a U.S. citizen.)

Teddy dispatched seven battleships with hundreds of Marines. Their mission: If Morocco’s government didn’t end the hostage crisis pronto, the Marines would seize the customs houses, which bankrolled that nation’s economy. If Perdicaris was killed, they were to find, attack and destroy Raisuli’s gang.

As the warships steamed across the Atlantic, someone in the State Department stumbled upon an inconvenient fact: Perdicaris was a Greek citizen, not an American. Never one to let details stand in his way (this was, after all, the president who said, “I took the (Panama) canal zone and let Congress debate”), Teddy charged ahead as planned. Raisuli thought Perdicaris was an American when he seized him; that was good enough for the White House. (In fact, Washington kept Perdicaris’ nationality a secret for 29 years after the kidnapping.)

With the warships nearing Morocco, Washington furiously worked behind the scenes for a peaceful resolution. Britain and France pressured the sultan to give in to Raisuli’s demands. It looked like bloodshed would be avoided. But there was a problem.

1904 happened to be a presidential election year. While all this was going on, the Republican National Convention was underway in Chicago. Delegates were ho-hum about Teddy’s re-nomination. (Remember, the country had inherited him after McKinley’s murder three years earlier.) There was little excitement about the coming fall campaign.

Then, eight words changed everything.

After making a big show of flexing America’s military muscle, Teddy feared he would look weak accepting a peaceful settlement. Knowing Morocco’s sultan was about to meet the kidnapper’s demands, Secretary of State John Hay sent a bluntly simple communique to America’s ambassador in Morocco: “This government wants Perdicaris alive or Raisuli dead.”

When the message was read to the convention, the delegates went wild. This was the famous Teddy Roosevelt they knew, the cowboy who had charged up San Juan Hill with guns blazing. Now, he was displaying courage and guts again, standing tall in the face of terrorism. The country rallied behind him as “Perdicaris alive or Raisuli dead” became a national catchphrase.

So when Raisuli, who was very much alive, released Perdicaris unharmed on June 21, the message was clear: Teddy had triumphed over the bad guys. Roosevelt sailed to re-election that November.

It’s easy to dismiss this episode as a comedic farce. No one was harmed, the U.S. wasn’t out anything but the cost of the coal to send its battleships across the Atlantic, the sultan was overthrown four years later, and Perdicaris and Raisuli even became friends during their time together.

But there was a serious side to what history now calls the Perdicaris Incident. When lives are at stake, Americans respond positively when a president displays courage. And while people cheer saber-rattling, they also expect our leaders to seize every opportunity to peacefully end a crisis.

Perhaps most important, nobody messed with Teddy Roosevelt again for the remainder of his presidency.

Washington can learn a lot today from that crisis back in 1904.

Please follow DVJournal on social media: Twitter@DVJournal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJournal