HOLY COW! HISTORY: Trump’s Attempted White House Return Faces Headwinds of History

The 2024 presidential race is unlike anything that’s happened in our lifetime. It’s a grudge match for the ages, a replay of 2020 that will likely end with either Donald Trump pulling a Grover Cleveland (by serving two non-consecutive terms), or with Joe Biden being the first president since Dwight Eisenhower to beat the same opponent twice in a row.

The last time a former president appeared on the November ballot for a shot at returning to the White House was in 1912, the year the Titanic sank. Perhaps that’s because, like the Titanic, most ex-president comeback attempts have been disasters.

Take Ulysses S. Grant. Winning the Civil War helped him sail into the White House in 1868. Though personally honest, Grant made the mistake of surrounding himself with men who weren’t. His administration was plagued by scandal, and he often bemoaned the burdens of the office.

In his farewell address at the end of 1876, Grant wrote, “With the present term of Congress my official life terminates. It is not probable that public affairs will ever again receive attention from me further than as a citizen of the Republic.”

But after a round-the-world tour with his wife, where Grant was loudly cheered and frequently feted, he changed his mind and entered the 1880 presidential race.

Unlike Trump, Grant was far from a lock when the GOP convention convened.

Popular Sen. James G. Blaine, R-Maine, had lined up solid support from the delegates and was neck-and-neck with Grant on the first ballot. But after a grueling 36 ballots (the longest-ever Republican National Convention), Grant lost to dark horse candidate Rep. James Garfield of Ohio, who went on the win the presidency. (And was assassinated soon thereafter.)

Another Republican president who desperately wanted redemption but got the boot instead was Herbert Hoover. In perhaps the worst timing in American politics, Hoover was elected in 1928, making him America’s president for the 1929 stock market crash and the Great Depression that followed. Not surprisingly, unhappy voters showed Hoover the White House door in 1932, replacing him with Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt. (Who, incidentally, went on to shatter George Washington’s two-term tradition by seeking — and winning — the office four times.)

Like Grant before him, Hoover was itching for another bite of the chief executive apple. Unfortunately for him, Republican voters didn’t feel the same way. After flirting with seeking the nomination in 1936, Hoover actually entered the race in 1940. For his trouble, he got nothing more than a mere 17 delegates and a warm round of applause at the convention.

In the pre-Civil War era, ex-presidents Martin Van Buren and Millard Fillmore both ran for the office again. And both failed miserably. But the Mother of all Presidential Comeback Attempts was in 1912. And it was a doozie.

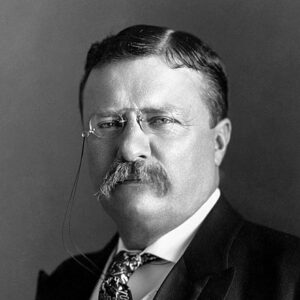

The assassination of William McKinley in 1901 made 42-year-old Theodore Roosevelt the youngest person to serve as president. In 1904, Roosevelt was elected in his own right. Then, in a move that still baffles historians, he did something incredibly stupid. Caught up in a moment of euphoria on Election Night, Roosevelt blurted out that he wouldn’t seek re-election in 1908.

Roosevelt regretted making the pledge but, as a man of his word, he was determined to keep it. And so in 1912, the man who perhaps loved being president more than any other handed over the reins to someone else.

His handpicked successor, William H. Taft, was easily elected. But there was a problem. Roosevelt was a progressive, and Taft was a conservative. The two quickly split, ending their close personal friendship and hurting Taft deeply in the process.

Teddy challenged his former BFF for the Republican nomination in 1912. Taft controlled the party machinery and had no trouble securing the nomination. And Teddy being Teddy, he bolted the GOP and ran on a third-party progressive ticket (nicknamed the Bull Moose Party).

That fractured Republican support, enabling Democratic progressive Woodrow Wilson to win the White House with just 42 percent of the vote.

And still, Teddy was ready to ride again. After considerable fence-mending within the GOP, including patching things up personally with Taft, Roosevelt was planning to run in 1920. Instead, he suffered a heart attack and died in his sleep in early 1919.

Fast forward to 2024: An incumbent president is preparing to face off against his immediate predecessor. The GOP is hampered by a significant number of Never Trump voters, while the Democrats’ progressive wing is increasingly angry with their party’s soon-to-be 82-year-old standard bearer. Add to that a host of independents (most notably Robert F. Kennedy Jr.) circling around both camps.

How will it turn out? Nobody knows. But this much is certain: You’ll want to have your history book handy once the result is known. Because it will need to be updated.

Please follow DVJournal on social media: Twitter@DVJournal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJournal