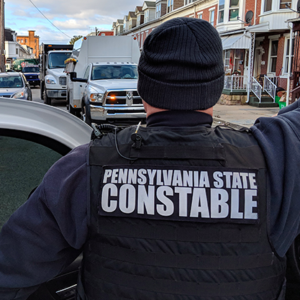

A recent high-profile criminal case involving constables has thrust the little-known law enforcement position back into Pennsylvania’s political spotlight.

Constable Joshua Z. Stouch, based mainly in Montgomery County, said if he had to estimate what percentage of the Pennsylvania population could describe what a constable does, “I’d put that anywhere from five to ten percent.”

The job’s roots go all the way back to the old world, where constable was one of the first kinds of police officer — a position preserved during the early days of Pennsylvania’s colonial founding.

Independent contractors who are elected for a six-year term and get paid on essentially by the job, constables can serve arrest warrants, handle landlord-tenant complaints and work security at magistrates across the state. “Once you say to someone ‘we’re the deputy sheriffs of the lower court level’ — the Minor Judiciary — they seem to at least have a general understanding of what it is that we do,” Stouch told Delaware Valley Journal.

In 2019, Republican State Rep. Barry Jozwiak introduced legislation that would have eliminated the elected position. In his memo introducing the bill, Jozwiak argued that as the role of constable has gradually waned since the founding days of the commonwealth four centuries ago, the remaining duties could be absorbed by sheriff’s offices.

But constables say they fill an important role of filling the gaps between the different layers of the Pennsylvania judiciary system, sheriff’s offices, and municipal police.

“Your day can go anywhere from you’re out the door at 6 o’clock for somebody that has a warrant, two hours later you’re serving an eviction, and two hours later you’re transporting a prisoner for a criminal hearing — and literally anything in between there,” Stouch said. He also argues the position is remains nimble and cost-effective.

A major difference, for example between a constable and a sheriff’s deputy is funding. Sheriff’s offices are funded by taxpayers, but constables are paid off of a fee structure.

“That fee bill is standard across the state for constables to be paid for service to the minor judiciary,” Stouch said. “It is paid either by the plaintiffs in civil cases such as landlord-tenant matters, lawsuits, etc. And in criminal matters, anything from parking ticket warrants all the way to felony murder, transports, et cetera, that is all paid for by the defendant then.”

Despite the many similarities to law enforcement work, there are also some key distinctions.

“A Constable may NOT enforce any provisions of the vehicle code (such as speeding, stop sign violations, etc), and they may NOT perform criminal investigations, which municipal and state police are authorized to do,” a Patch op-ed from 2016 noted. “For example, the neighbor of a Constable cannot contact him to investigate a burglary that was just discovered or to investigate vandalism to their vehicle.”

Yet at the same time, constables still retain the wide power to arrest, “for any breach of the peace or crime committed in their presence,” Stouch said.

In the recent court case drawing fresh public attention, a judge dismissed 54 felony counts against a security manager for the Mariner East pipeline who had been accused of bribing constables to do security work while using their badges.

Although it’s generally not contested that constables may hire themselves out for private security contract jobs, they are prohibited from using the official insignia of the job — such as a badge — while doing that kind of work.

John Pfau, the manager of the bureau of training service for the state Commission on Crime and Delinquency, told the Inquirer that the case exposed lingering problems with oversight of the position.

“It’s this schizophrenic set of case law and statutes that in some cases dates back 70, 80 years,” he told the paper. “A constable is an independent contractor for the minor judiciary, but the problem is, it’s never been addressed. There’s no clear list of what constables can and can’t do.”

Stouch, who serves as the legislative director for the Commonwealth Constables Association, said he firmly believes the role of the constable is a bargain for citizens.

“We are elected for and by the people of our communities to serve at the pleasure of the judiciary,” Stouch said. “We are the most cost effective and best equipped to handle local issues when it comes to serving as a law enforcement arm of the judiciary. We generally do not cost taxpayers any money.”

“Generally speaking, we are one of the most cost-effective law enforcement services in the commonwealth.”