This article first appeared in Broad + Liberty.

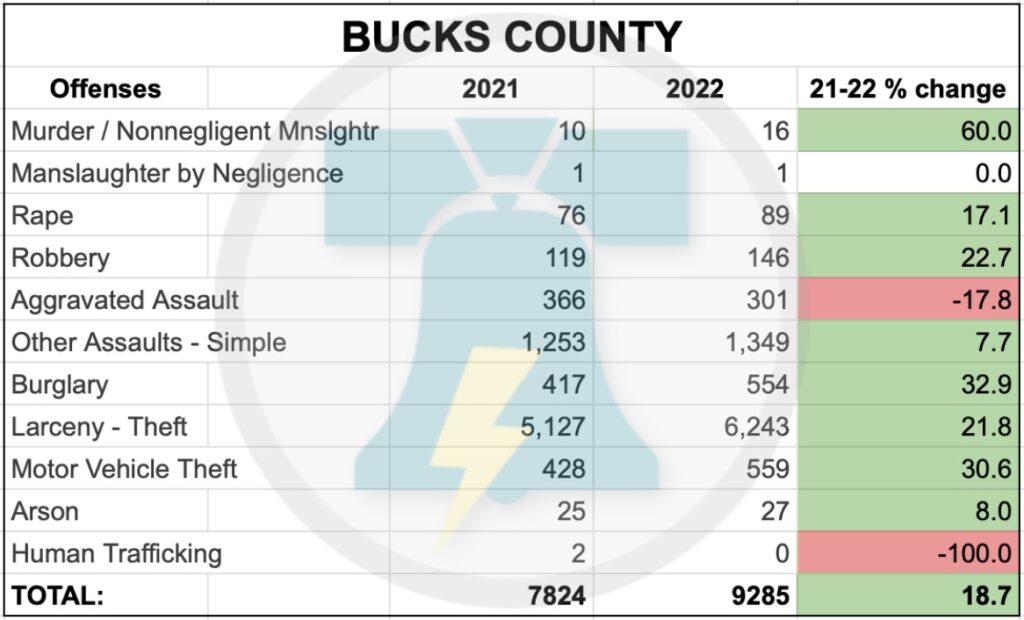

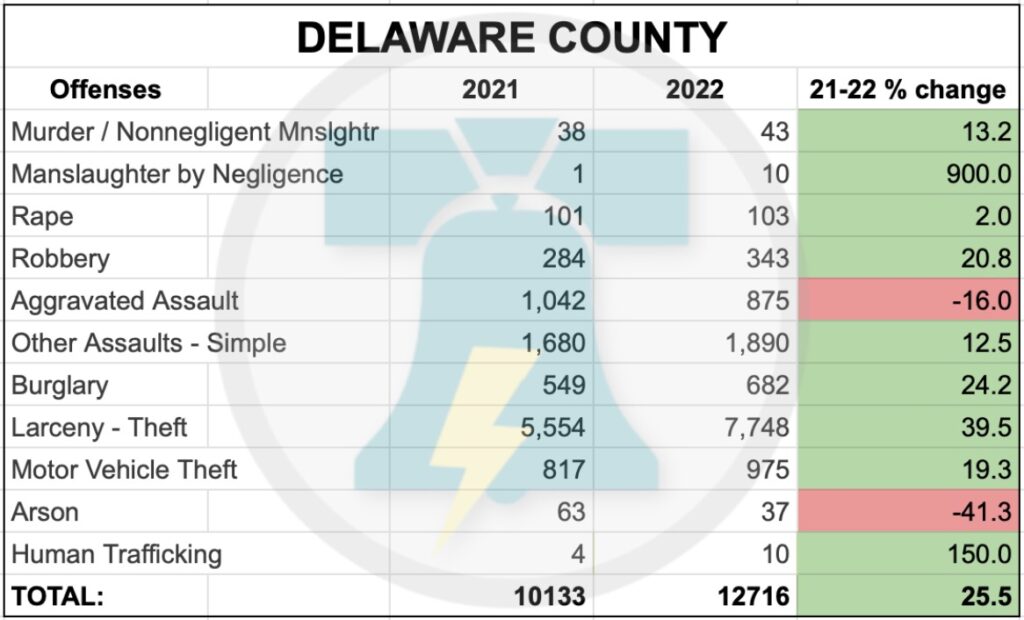

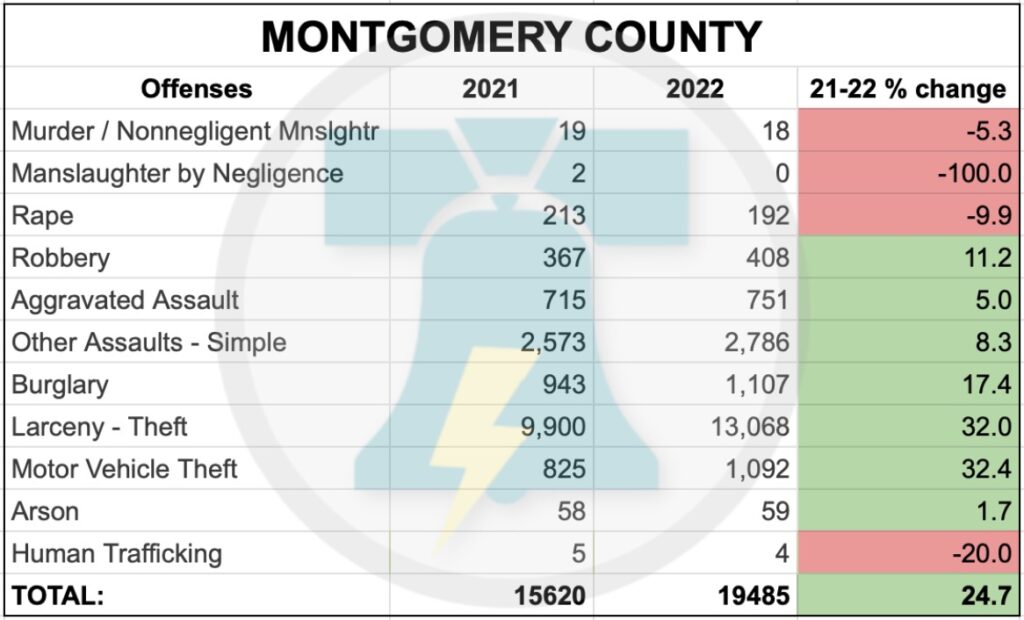

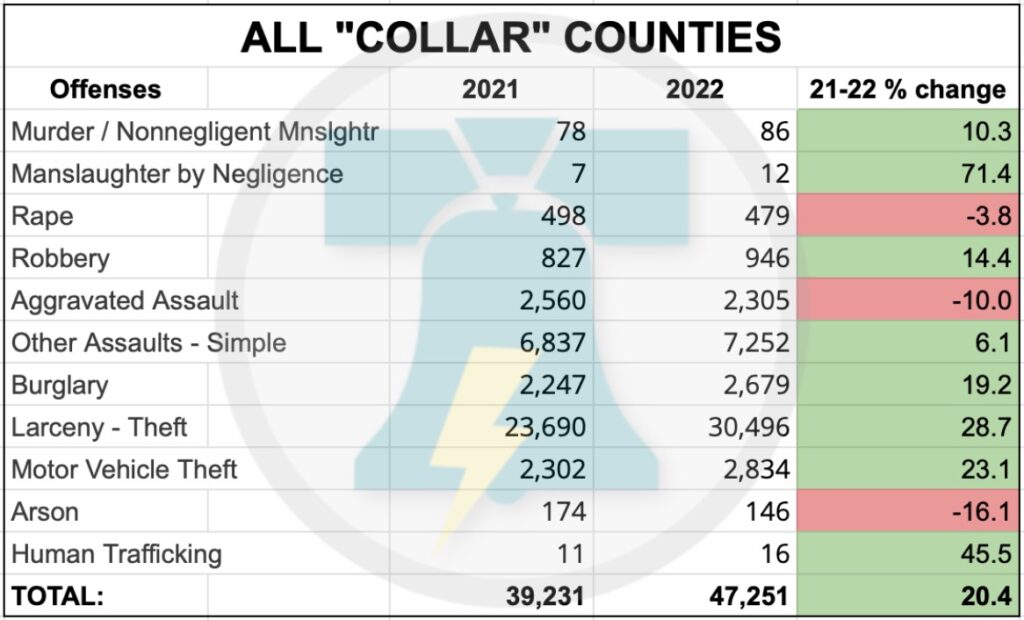

Crime rose by double-digit percentages in Delaware, Montgomery, and Bucks counties from 2021 to 2022 with the largest increases coming in property crimes like burglary, larceny, and motor vehicle theft, according to data from the Pennsylvania Uniform Crime Reporting System (UCR) website.

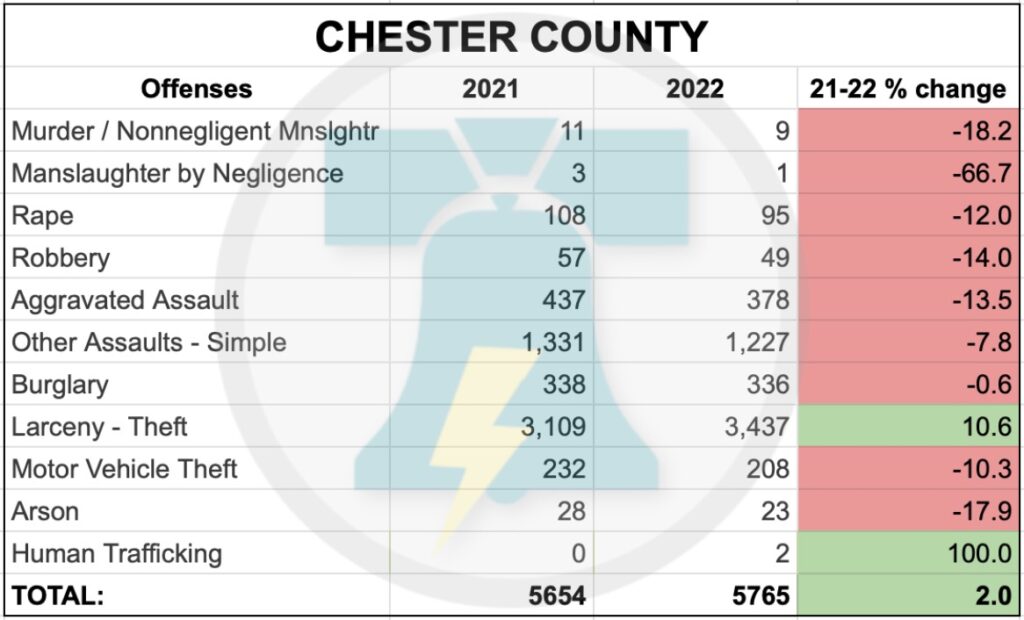

Chester County, which does not share a border with Philadelphia, was the only “collar county” bucking that trend. There were decreases in nearly every category but one.

The statistics represent one of the most definable contours placed on the otherwise uneasy and oftentimes fuzzy notion driven by anecdotes that an urban crime spike in the summer of 2020 is spilling over beyond the Philadelphia city limits, impacting smaller communities not normally affected by assaults or thefts.

Larceny (generally defined as theft of personal property) and auto thefts in particular are both showing large increases in the collar counties that match large increases in Philadelphia.

Taking the four counties combined, auto thefts climbed from 2,302 in 2021 to 2,834 in 2022, an increase of 23 percent.

Those figures compare to a dramatic spike in auto thefts in Philadelphia. In 2022, the city reached a two-decade-long high of 14,533 car thefts, up from 11,341 in 2021. This year, however, the city is set to blow past both of those figures, as the current trend shows Philadelphia will likely surpass 20,000 car thefts in 2023.

As stark as the increase in auto thefts seems, the percentage increase in larceny in the four counties eclipsed even that.

In 2021, the four counties totaled 23,690 incidents of larceny, which rose to 30,496 by 2022 — an increase of 28 percent. Larceny was the one category in Chester County showing a year-over-year increase.

Burglaries were up 32, 24, and seventeen percent in Bucks, Delaware, and Montgomery, respectively from 2021 to ‘22.

Three categories did show decreases. Reported incidents of rape were down four percent. Aggravated assaults were down ten percent, and arson was down sixteen percent.

When adding all the categories together, the number of total incidents reported across the four counties was up twenty percent.

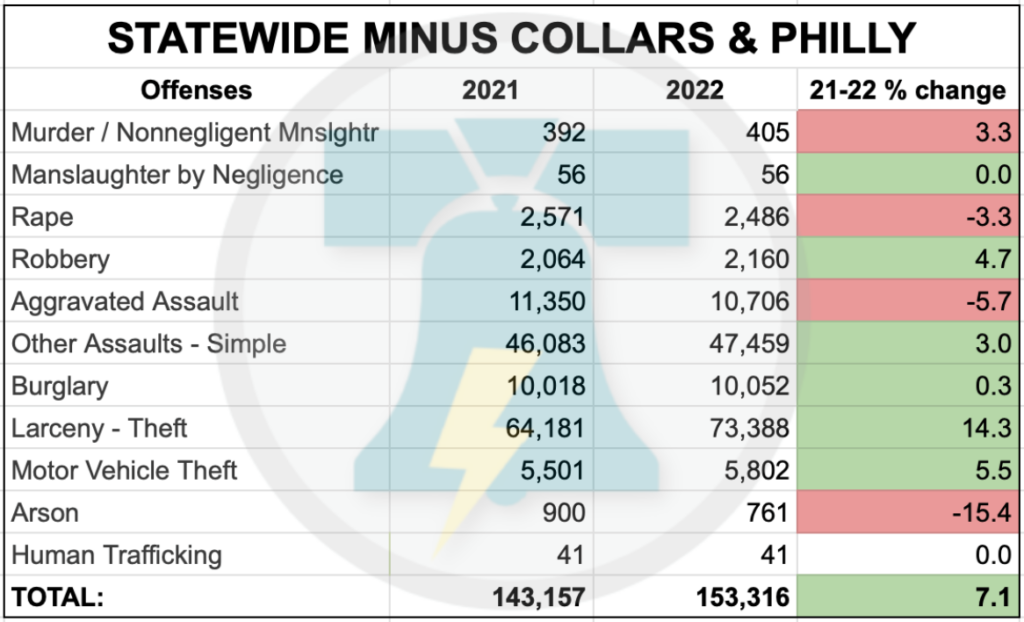

Comparing the numbers against the rest of the state appears to show that most of these increases are concentrated in Southeast Pennsylvania.

For example, taking statewide data that subtracts Philadelphia and the four collar counties shows larcenies were up fourteen percent in the remainder of the commonwealth. In the four collar counties, larcenies were up twice that rate, at 28 percent.

The data also appear to show that the skyrocketing auto theft trend is also primarily a southeastern phenomenon.

While motor vehicle thefts are up 40 and 23 percent in Philadelphia and the collar counties, respectively, they are only up five percent in the rest of the commonwealth.

Burglaries were mostly flat in the rest of the state from ‘21 to ‘22. However, burglaries were up nineteen and ten percent in the collar counties and Philadelphia, respectively.

Broad + Liberty’s requests for comment to the district attorneys in the four suburb counties were not returned. (Montgomery and Chester counties acknowledged receiving the questions and appeared ready to engage at first, then stopped communicating.)

Of the four incumbent district attorneys in the collar counties, only Jack Stollsteimer (D) in Delaware County faces a re-election battle, running against Republican Beth Stefanide Miscichowski. Chester County District Attorney Deb Ryan (D) is not running for re-election this year, opting to run for a judgeship instead. Kevin Steele (D) in Montgomery County is running unopposed. And the district attorney office is not on the ballot this year in Bucks, but Weintraub is also running for a judgeship.

Many of the incumbent district attorneys have claimed success in battling gun crimes, something not directly addressed by the statistics in the Pennsylvania UCR.

On his re-election website, Montgomery’s Steele said his office had “strategically focused on: A) homicides; B) illegal guns on our streets: ghost guns and gun traffickers putting deadly weapons in the hands of criminals; C) drug traffickers who are killing people by peddling their deadly poisons like fentanyl and other drugs; and D) those who cause harm to women and children.”

In Bucks County, Weintraub said in October: “One trend we’re seeing across the state is younger and younger people, especially minors, are the population rising the quickest [for] carrying firearms.”

In January, Delco DA Stollsteimer wrote an op-ed promoting what he perceived as the greatest successes in his tenure.

“We have reduced the gun violence homicide rate in the City of Chester by 60 percent and the overall number of gun violence incidents by 46 percent,” Stollsteimer wrote. The only other measurement he provided in the piece was to say, “Through collaboration and innovation, my team has spearheaded a 30 percent reduction in the prison population here in Delaware County.”

Delaware County Council Member Kevin Madden asserted that a two-year drop in crime supported the collaborative push with Stollsteimer to drastically reduce the number of persons incarcerated at the county correctional facility, and the length of those stays.

“In 2020, [the county prison] population was nearly 1,900,” Madden said. “It’s really down by 35 percent in two years. That’s extraordinary. Our crime rates are lower than they were two years ago.”

Data from the UCR don’t support his assertion, however, at least in the most recent years and especially the ones in which the county’s management takeover of the correctional facility has coincided with the decarceration effort.

Arrests and prosecutions were notably lower in 2020 because of the pandemic. Therefore, when using the last non-pandemic year and measuring Delaware County’s total recorded incidents from 2019 to 2022, total incidents increased by ten percent. But to take Madden literally by comparing 2022 to 2020, total incidents were up 30 percent.

A request for comment to Madden on this issue was not returned.

In Chester County, the candidates are debating the extent to which crime trends have shifted in the county.

“In the last few years, you’ve seen crime in Philadelphia starting to creep out more and more into the counties. And it’s not just Philadelphia; it’s Wilmington,” Republican candidate Ryan Hyde said. “I talked to a narcotics (officer) the other day in Kennett Square, who told me most of the drugs in the lower part of the county are now coming up through Wilmington. And I know a lot of stuff is coming through Baltimore.”

Democrat candidate Chris de Barrena-Sarobe disagreed.

“But if you look at studies, crime is down across the board,” said de Barrena-Sarobe. “I don’t think there’s been a homicide in Chester County all year…My perception is there is no significant change in crime in Chester County.”

Both can claim to be correct, according to the statistics. Hyde’s assertion that Philadelphia crime is creeping out into the counties appears to be correct, even though Chester has been spared the brunt of the increase. Data for 2023 in Chester County shows there has been one offense tallied for murder/non-negligent manslaughter.

The most political change on crime in southeast Pennsylvania arguably landed last week, when Philadelphia Democrats chose former state representative and city councilor Cherelle Parker as the party nominee for mayor. Given the lopsided registration advantage Democrats enjoy in the city, Parker’s election as mayor in November against Republican David Oh seems a fait accompli.

“Parker’s path to victory was never guaranteed, but it was powered by Black and Latino voters — particularly residents of the poor and low-income neighborhoods hardest hit by the city’s gun violence crisis,” an Inquirer report noted. “Areas with the highest concentrations of shootings, particularly parts of North and West Philadelphia, handed Parker roughly half their votes in a field with five top contenders, an Inquirer analysis showed.”

A major plank of the Parker campaign was bolstering Philadelphia’s police ranks, worn down by the attrition of retirements and quittings, both of which seemed to accelerate in the heightened scrutiny of the post-George Floyd era that ushered in the #DefundThePolice movement.

Meanwhile, many municipal police leaders, police unions, and locally elected Republicans have been sounding the alarm for more than a year.

The House Republican Policy Committee (which is not an official committee within the General Assembly, but is a mechanism both parties use to discuss issues with various stakeholders which informs the drafting of legislation) has held two hearings on crime or public safety recently, one in early May, and the other in October.

In both cases, police officials, union leaders, and district attorneys pointed the finger — with varying degrees of subtlety — at Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, accusing him of fostering a region-wide culture that committing serious crimes was consequence-free.

In the October hearing, Bensalem Public Safety Director William “Bill” McVey did not mince words when claiming Krasner’s policies in Philadelphia were impacting the crimes in his township.

“This is an ongoing problem with the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office. The District Attorney’s Office of Philadelphia has also decriminalized retail theft if it’s under $500. This has had a devastating impact not only on Philadelphia, but on all surrounding municipalities. In Bensalem, retail theft is up 29 percent this year, and that’s after Macy’s is closed, Sears is closed, and K-Mart has closed — stores that typically had the most retail thefts in our township.”

At the same meeting, Bucks County District Attorney Matt Weintraub echoed those ideas, but was more circumspect about naming Krasner.

“The bottom line is the criminals don’t know the boundaries — they don’t know and don’t care about the boundaries between some lawless areas of the state, and some others that may be more law abiding,” Weintraub said.

The same themes were heard at the more recent hearing by the House Republican Policy Committee this May.

A request for comment on those ideas to the Philadelphia district attorney’s office was not returned.

Reporting on crime has long been a thorny issue because statistics can be hard to gather and standardize. That’s no different for the Pennsylvania UCR as the accuracy of the data is difficult to determine.

The Pennsylvania State Police, which maintain the website that smaller law enforcement agencies contribute their data to, says on the website, “The accuracy of the statistics depends primarily on the adherence of each contributor on established standards of reporting; therefore, it is the responsibility of each contributor to submit accurate data and to correct any data found to be submitted in error. It is important to note that participation in the program by law enforcement agencies is voluntary.”

Broad + Liberty’s own reporting has called the data into question before. Last August, we reported that Upper Darby’s police department was underreporting homicides to the UCR, something the township’s police appeared to remedy after our article was published.

Among the many questions sent by Broad + Liberty to the local district attorneys in the collar counties was asking the degree of faith each DA had in the UCR as an indicator of crime trends in their jurisdiction.

Comprehensive crime reports by the Federal Bureau of Investigations used to be relied upon heavily by governments and the media, but have faltered recently as more major cities across the U.S. have stopped participating. Those reports also lag by well over a year, thereby making them less useful as a real-time tool for law enforcement agencies and policy makers.