A newly released film depicting activists planning the destruction of a Texas oil pipeline has reignited a longstanding debate about violence in the media. Could violent portrayals in movies and other art forms lead to real-life violence?

In Southeast Pennsylvania, where there has been heated debate for years over a local pipeline project — including a local Democrat who compared pipeline workers to Nazis — the conversation is more than academic.

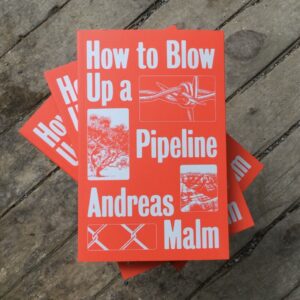

The movie “How to Blow up a Pipeline” got its title from a 2021 book by Swedish writer and activist Andreas Malm. In it, Malm suggested environmentalists should consider aggressive, violent destruction of fossil fuel infrastructure to fight climate change’s purported effects.

“Damage and destroy new CO2-emitting devices. Put them out of commission, pick them apart, demolish them, burn them, blow them up. Let the capitalists who keep on investing in the fire know that their properties will be trashed,” Malm wrote.

Andreas Malm speaking at Code Rood Action Camp 2018 in the Netherlands (CREDIT: Code Rood, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

But instead of denunciations, Malm became a media darling. In a 2021 podcast, Malm told New Yorker writer/editor David Remnick that the green movement should reconsider its roots in non-violence. He said he believes it is time to get destructive as a way of combating man-made climate change and forcing people to depend less on fossil fuels.

“I am not saying we should stop [climate] strikes or square occupations or things like that,” Malm told The New Yorker Radio Hour. “I am recommending that the movement continues with mass action and civil disobedience but also opens up for property destruction,” Malm said.

Now his book has inspired a movie.

Daniel Goldhaber, who directed the film, said he and his partners sought to create a movie that “wouldn’t necessarily be calling for action, or telling audiences to go and [blow up a pipeline].” Rather, he said, they worked to “depict characters for whom the destruction of the infrastructure is an act of self-defense.

“We understand that if there is a gun to your head and someone is intending to pull the trigger and kill you, you have a right to take the gun away and dismantle it,” Goldhaber continued. “Proverbially, the fossil fuel industry has a gun to the head of the Earth. So the question is, do we have the right to take the gun away and dismantle it?”

Max Abrahms, an associate professor of political science at Northeastern University who specializes partly in the study of terrorism, said media like “How to Blow up a Pipeline” does actually “raise some very real ethical questions.”

“The vast majority of people who have even extreme eco-goals, they’re not very violent,” Abrahams said. But if the film “would increase the chances of people moving into the violent category, that would be potentially problematic.”

James Forrest, a criminology professor at the University of Massachusetts Lowell who studies homeland security and critical infrastructural protection, said it is “hard to say whether this recent film would stand out as exceptional in any way” compared to other films that depict violence and/or terrorism.

Extremists “can already access a variety of instruction manuals online and via bookstores,” he explained, “and countless YouTube videos are showing how to make IEDs, IIDs, chemical weapons, and much more. So it’s not like they would need a film like this to give them any kind of information they don’t already have access to. “

Forrest pointed to a longstanding extremist tactic of attacking infrastructure like pipelines, including most recently the destruction of the Nord Stream pipeline in the Baltic Sea.

In the U.S., in recent years, environmental activists have also been known to target SUVs, pickup trucks, and other large vehicles, deflating them in the act of protest against cars that consume heavy amounts of fuel. One such act of sabotage is depicted at the beginning of “How to Blow Up a Pipeline.”

The recently-completed Mariner East 2 pipeline inspired emotional opposition during its construction in the Delaware Valley, though there was no violence. Some were arrested for trespassing and minor crimes as activists broke the law to show their opposition.

And Democrat state Rep. Danielle Friel Otten was forced to apologize after comparing the rank-and-file pipeline workers to Nazis.

Craig Stevens, president of the group Grow American Infrastructure Now, said in a statement the film “glorifies the dangerous and criminal act of eco-terrorism.”

Oil and gas “are the lifeblood of our modern economy and way of life,” Stevens said, pointing out that without fossil fuels, “we couldn’t drive; heat our homes; or power our schools, businesses, hospitals, or homes.”

Amy Cooter, a senior research fellow at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies, pointed out that “property destruction and attacking energy sources (of multiple kinds) are already in the repertoire of more than one group, so it’s unlikely that a film would be a lone cause for such an attack.”

“We generally have very broad protections for freedom of speech,” she added, “so if, hypothetically, someone did execute an attack based exclusively on inspiration from a film, it would be incredibly unlikely that the filmmakers would face any kind of legal repercussions.”

The film itself has been warmly received in critical circulars, though not without caveats. Rolling Stone called it “the hottest date movie of the season,” while Variety dubbed it a “taut indie drama.” The Los Angeles Times, meanwhile, begged readers, “Please don’t blow up a pipeline after seeing this film.”

Whether or not the film will ultimately lead to violent environmental action remains to be seen. Critics have long attempted to draw a line between violent media and violent behavior, such as repeated claims by now-disbarred lawyer Jack Thompson that violent video games inspire violence in the youth that play them.

Goldhaber called such allegations “spurious from the beginning.”

“The people who may try to condemn this movie are afraid of the conversation around the film,” he claimed. “I would ask: Why talk about this film? Why not talk about the billions of lives that are on the line due to climate change right now?”