HOLY COW! HISTORY: The Pictures That Never Made It Home

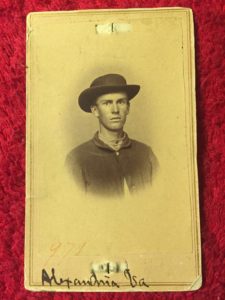

The Yankee soldier stares at us with a hard glint in his eyes. Wiry and weathered, he’s ready for action. No name, no date, no unit. Just a young man whose face shows the strain of war.

What makes this photo remarkable is the “971” in faded red ink in the lower-left corner, two empty slots at the top and bottom, and “Alexandria, VA” in period handwriting.

They indicate the Civil War image came from the post office’s Dead Letter Office (DLO).

Postal workers stayed incredibly busy from 1861 to 1865. Some 2.5 million men served in the Union army alone. Many wrote letters home. And the folks there wrote back. Meaning tens of thousands of pieces moved through the mail every day.

But there were logistical headaches. Some soldiers were barely literate. Others had sloppy handwriting. They didn’t always affix adequate postage. And many letters were improperly addressed. By the time some letters reached their destination, they were so badly marked up by various postmasters they looked like they had come through combat themselves.

Whenever one couldn’t be delivered, it wound up in the DLO in Washington. Operating since 1825, for much of the 19th century it was, along with the Pension Bureau and Patent Office, a “must-see” stop for D.C. tourists. It was so popular, it even had a small museum displaying oddities discovered inside letters whose owners were never located. Such as a loaded pistol and a human skull.

By war’s end, some 4.5 million pieces of mail had piled up in the DLO. Special clerks examined each one for clues about the addressee that local postmasters had missed. When external examination failed, clerks had authority under a law passed by Congress to open an envelope to see if the letter contained hints about the recipient’s identity. Those clerks were often women and ordained ministers since it was believed they were more trustworthy when handling sensitive data. They were so skilled at their work, more than 40 percent of DLO letters were eventually delivered.

Soldiers’ letters sometimes contained photos meant for mothers, wives, sweethearts, and friends. They were saved and the pictures added to the DLO’s mini-museum.

Each soldier’s photo was numbered in red ink and attached with two brass clips to a cardboard display panel. Four rows containing nine pictures each, or 36 per page. It is estimated there were somewhere been 5,000 and 7,500 images in all.

Visitors scanned the pages. If they came upon someone they knew, they got the letter.

The display was such a hit, a special wooden case was built to hold the photo panels. Emotions often bubbled to the surface during the viewing; women frequently sobbed while looking for a lost loved one’s face.

The photos were even taken to world fairs where tens of thousands of attendees saw them. Consider the 1898 Trans-Mississippi and International Exhibition in Omaha, Neb., where a woman spotted an image of her father taken 35 years earlier. (That letter was returned to the elderly veteran in Indiana.)

In 1902, another aging veteran claimed the letter he had mailed exactly 40 years earlier!

Veterans’ organizations, such as the Grand Army of the Republic (similar to today’s VFW and American Legion), and newspaper and magazine feature stories were also used to publicize the effort.

A newspaper article reported that in all, some 2,000 letters were eventually delivered thanks to the photos.

But thousands more went unclaimed. When the post office moved into its new Washington building in 1911 (now a Trump hotel, by the way), the DLO went with it. Its little museum, however, didn’t. With the Civil War becoming a distant memory, fewer people asked to see the pictures. The display was put in storage. It was decided to sell the images in the 1940s. (Nobody knows what happened to the letters that inspired the display. They seem to have simply vanished over the decades.)

One group of 300 DLO photos wound up in a New York bookseller’s hands after World War II. They were later sold to the George Eastman Museum. A second batch was acquired by a Sons of Union Veterans commander. Those images were eventually auctioned off in the 1980s.

Where did the Dead Letter Office photos originate? We’ll never know. The identity of the soldiers shown in them, or who they intended to receive their photographs, went to the grave with them. Maybe that’s why they glare at us so unhappily nearly 160 years later. In their own small way, their pictures were also a casualty of that saddest of all wars.

Please follow DVJournal on social media: Twitter@DVJournal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJournal