Oct. 7 Remembrance Ceremony Brings Tears, Hope

Artist Judy Rohtbaut of Wynnewood was among the 1,000 or so people who attended the Oct. 7 remembrance at Har Zion Temple in Penn Valley on Sunday.

“It was very powerful,” said Rohtbaut, whose parents were Holocaust survivors. “And [it] so strongly brought the message home of how Israel needs support.”

That was the goal of the ceremony, featuring music, prayers and talks, both in person and on video, about the experiences of survivors, hostage families, and Israeli Defense Force (IDF) soldiers.

October 27 was the one-year anniversary of the Hamas massacre, according to the Hebrew calendar. The event was sponsored by the Jewish Federation of Greater Philadelphia.

The gathering also featured a moment of silence was observed for those who died in the Tree of Life synagogue mass murder in Pittsburgh six years ago that day.

“I would have liked to come here under different circumstances. Prior to the war, I had a very ordinary life as an Israeli citizen,” said Eldar Mayder, a reserve IDF soldier told the attendees. “I worked. I spent my weekends at the beach, playing volleyball or surfing.”

“On Oct. 7, 2023, on the Jewish holiday of Simchat Torah, the Hamas terrorist organization launched a deadly genocide attack against Israeli men, women and children. And everything changed.”

He awoke to sirens blaring at 6:30 in the morning, contacted the leader of his unit, grabbed his weapon, and headed to his army base.

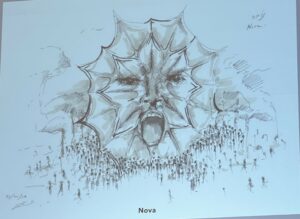

The Nova music festival where terrorists slaughtered many young attendees is the topic of a drawing by IDF soldier and artist Iftach Mashal.

“After a few days of fighting, we were able to stop this horrendous attack. We went into the Gaza strip to save the hostages and bring those who committed this massacre to justice, to make sure they will never be able to threaten Israel again.”

A member of the unit tasked with rescuing the 251 hostages, including Americans, he noted that every Gaza house they went into and even incubators for babies in hospitals “contained unprecedented amounts of weapons.”

The huge sums of money spent on weapons could have gone to help the people of Gaza, he said.

Nearly every house had a copy of Adolf Hitler’s book, “Mein Kampf” translated into Arabic, he added.

“It’s a bestseller in Gaza,” Mayder said. “We found thousands of copies of this book.” Hamas “has filled the minds of an entire generation raised to hate Jews,” he said.

The Israeli soldiers also found photo albums with “pictures of kids holding AK-47s (rifles) and wearing suicide vests.”

He compared the Hamas terrorists to those who crashed planes into the World Trade Center.

In March, Mayder received permission to travel to the U.S. to talk about the war with students on university campuses, including Harvard and M.I.T. He was “surprised by the level of deep ignorance and false information about Israel” among students at “the best universities in the world.”

They want to “boycott, divest and sanction the only Jewish state,” he said. Mayder, talked to LGBTQ protestors for Hamas who “the minute they step into Gaza would be thrown off roofs.” But Jewish professors and students are not safe and afraid to wear a yarmulke in public.

The IDA has the “highest moral values” of any army on the planet, he said.

Experts like John Spencer, who teaches Urban Warfare Studies at West Point, cite the IDA warning civilians to evacuate ahead of an attack, putting their own soldiers at risk.

“Ladies and gentlemen, I assure you of one thing, we will win,” Mayder said to applause. “First, we don’t have any other choice. Israel is our homeland. Second, our enemies will learn the lessons (enemies) from the ancient Babylonians to the Seleucids and the Persians, the Inquisition, the perpetrators of pogroms in Eastern Europe to the Nazis have learned for the last 4,000 years… Israel will not bend…Am Yisrael Chai [Israel lives].”

Members of hostage families lit candles for hope and for the 1,200 who died in the attack.

Sorrowful drawings from IDA soldier Iftach Mashal that depict the Oct. 7 massacre were on display, several with forlorn, abandoned teddy bears, a reminder of the children lost. The pictures showed scenes from the kibbutzim where terrorists killed innocent residents, the Nova music festival and combat in Gaza. While Mashal was unable to attend the ceremony, two other IDF soldiers read from their unit’s war diary. Some 762 IDF soldiers have died in the ongoing conflict as of Oct. 27.

Hostage families lit candles in the hope that their loved ones will return.

Young students from Perelman Jewish Day School sang “Hatikvah,” the Israeli national anthem, to close the somber ceremony.

Rohtbaut, whose portraits of 40 of the hostages are part of a traveling exhibit that began in the Weitzman National Museum of Jewish History in Philadelphia, told DVJournal that, a year later, the horror of the event was still difficult to process.

“It’s just so shocking. Who would ever imagine this would happen?”