HOLY COW! HISTORY: When Hawaii Had Its Own Money

Think fast. You’re Lt. Gen. Delos Carleton Emmons. You’ve just been assigned a critically important new command. It was attacked by the enemy less than two weeks earlier, and the threat of imminent invasion is very real. What are your top priorities?

That was the situation confronting the three-star general when he arrived in Hawaii on Dec. 17, 1941. Japan had delivered its devastating sneak attack on U.S. military facilities at Pearl Harbor just 10 days earlier. Emmons was all too aware that those islands were all that stood between the Empire of Japan and the West Coast of the U.S. As 1941 drew to a close, whether the Stars and Stripes would continue flying over them in 1942 was far from certain.

While Emmons’ immediate focus was defending the vital outpost in the Pacific, he also had to safeguard against harmful consequences should it fall. For instance, if Japan were to invade and seize the territory (Hawaii wouldn’t become a state until 1959), the conquerors could also get all its currency.

It was a lot of currency, too. In that era before online banking, business was conducted in cold hard cash. Even if military authorities got word an invasion force was heading for Hawaii, there was no way all that money could be rounded up and sent to safety on the mainland. And should Japan seize it, a sizable financial windfall would suddenly be available to fund its war machine.

Necessity is the mother of invention, they say. If the cash couldn’t be carried off the island, the cash could at least be rendered obsolete if it fell into enemy hands.

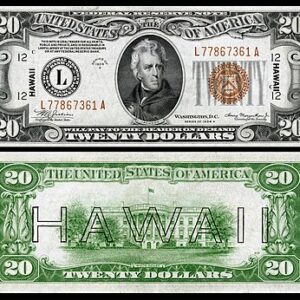

Starting on Jan. 19, 1942, Emmons’ troops collected all the banknotes they could find. “HAWAII” was printed across the back of each bill. The name was also discreetly added twice on the front. That way, in case the money wound up in the wrong hands, Washington could quickly repudiate it, making it worthless. All notes not containing the overprint had to be turned in by July 15. Starting August 15, regular notes couldn’t be used in the territory without special permission.

Limits were also placed on how much cash you could keep on hand. (The cap was $200 for individuals and $500 for businesses, minus payrolls.)

Those restrictions remained in effect until Oct. 21, 1944. By then, Japan was clearly on its last legs, and the threat of invasion had long since passed.

All in all, the system worked pretty well. Until the war ended.

Suddenly, there were piles of cash with “HAWAII” slapped across the reverse. The old notes were recalled in April 1946, and some $200 million was taken in. It was just too much to lug back to California. Now officials had a new dilemma on their hands: what to do with it.

For years, the government has been accused of burning through dollars. And that’s exactly what it did this time.

A local crematorium was pressed into service, and the special money was set aflame. Then a new headache arose. Literally. Small pieces of unburnt currency were carried up the chimney and swept away with the wind. It was a counterfeiter’s dream come true. So, special mesh wire had to be placed over the smokestack to keep unburnt bits from blowing away.

When the job proved too big for the crematorium alone to handle, the much larger furnaces at a nearby sugar mill were also used.

In time, the last of the emergency “HAWAII” money was destroyed. However, some 9 million pieces of it had been printed, and the government hadn’t recovered all of them.

Some locals hung on to the bills as keepsakes, and service members also brought some home as souvenirs. Eighty years later, they’re now valuable collectibles, with certain highly desirable examples selling for thousands of dollars each.

While Emmons’ quick financial thinking may have saved the day back in early 1942, he’s also remembered for something he didn’t do. As Japanese Americans were being rounded up on the mainland and held in special internment camps, he strongly resisted efforts for a similar move in Hawaii. It was one situation that didn’t have to be rectified later.

Please follow DVJournal on social media: X@DVJournal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJournal