EPA Is Blocking Biden’s Push for US-Made Microchips

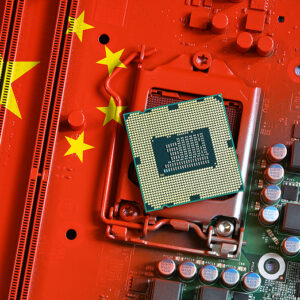

President Biden says making high-tech microchips in the United States is a national security priority instead of buying them from abroad. In August 2022, he signed the CHIPS and Science Act, making $280 billion available to domestic semiconductor research and manufacturing operations — a response to growing concerns about U.S. reliance on China’s production facilities.

“We went from producing 40 percent of the world’s chips to just doing 10 percent. But not anymore,” Biden said in a November 27 speech. “All over the country, semiconductor companies are investing hundreds of billions of dollars to bring chip production back home to the United States.”

But the same day Biden was making that speech, the Environmental Protection Agency was continuing its push to practically ban the production of chemicals like methylene chloride, perchloroethylene (PCE), and carbon tetrachloride (CTC) — all vital to the production of those chips.

Which leaves the U.S. microchip industry and its suppliers caught in the middle.

The EPA wants to curtail the chemicals used to make polysilicon, the basic material of computer chips — an obvious obstacle to domestic production. For example, semiconductor manufacturing requires massive amounts of PFA resins, made with chloroform — a co-product of methylene chloride and CTC – for tubing that pipes liquids, slurries and gases around facilities.

The EPA’s rule would also override current workplace regulations from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, adding a redundant layer of bureaucracy and a roadblock to America’s path to tech independence, industry sources say.

A $40 billion, taxpayer-subsidized chip-making plant (known as a “fab”) in Arizona is useless if the chemicals needed to make the chips are either banned or become so costly that manufacturing is no longer realistic. Members of the administration have acknowledged the dilemma.

“We can have as many fabs as we want, but the reality is, we also need the supply chain — the chemicals, the material, the tools that go into those fabs,” Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo said at a briefing earlier this year.

In a lengthy comment on the EPA’s proposed rule changes, the Semiconductor Industry Association said its members “are aware of numerous chemical substances in use at their facilities that are absolutely essential to the continued production of reliable semiconductors and to the expansion of production facilities and capabilities in the U.S. under the CHIPS and Science Act.”

The EPA has proposed another rule change that could further hamstring semiconductor research and development. It would eliminate low volume exemptions (LVEs) for new formulations of PCE, which chipmakers continually develop as part of their product-innovation process.

If the LVE exemptions are eliminated, every new chemical formulation would be subject to EPA reviews called premanufacture notices (PMNs). According to David B. Fischer, an attorney and former deputy assistant administrator at the EPA, completing those reviews can often take over a year. That is yet another obstacle to the stated goal of the CHIPS Act.

“The PMN process has been a significant frustration for scores of industries who rely on innovation to stay competitive,” Fischer said. “If a PMN gets bogged down for years, then companies opt to go offshore.”

Beyond the conflicting goals of CHIPS to foster domestic production on the one hand and the determination of EPA to restrict the use of PCEs through various schemes on the other, the realities of today’s global economy could render the entire issue moot, leaving the United States further reliant on foreign suppliers of semiconductors.

Large manufacturers with deep pockets won’t wait forever for U.S. policymakers to settle their conflicts before the chipmakers decide to just pull up stakes and build production facilities overseas.

Charles Wessner, an adjunct professor of science, technology and international affairs at Georgetown University and a senior adviser at the Centers for Strategic and International Studies, conceded that semiconductor manufacturing requires “some nasty products that have to be treated carefully.”

Nevertheless, he said, for decades, the industry has demonstrated a positive commitment to environmental safety. “These aren’t people who dump toxic waste into pristine streams,” says Wessner, who previously founded and directed the National Academy of Sciences’ Technology, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship Program.

“If we’re going to compete and protect ourselves against hostile powers and create wealth, we need to adjust the balance between environmental protections and supporting new growth.”

According to Wessner, the average salary of workers in the industry is $95,000. A typical semiconductor plant creates thousands of well-paying jobs directly and indirectly, serving as a major catalyst for regional economic revivals.

“Some want sensible rules, but we need to get past the obstructionists,” he said. “People are deeply attached to their smartphones without acknowledging the toxic materials required to produce them. They want clean energy but don’t want any windmills in their backyards. They don’t want any fields nearby covered with solar panels or transmission lines anywhere in sight.”

“It doesn’t just fall from heaven,” he added.

Please follow DVJournal on social media: Twitter@DVJournal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJournal