Did Memorial Day Originate in a Small Pa. Town? Maybe Not, But That’s Okay

Traditions have a way of getting tangled up in fact, myth, and legend, making historical confirmation a bit of a chore.

George Washington, for instance, is often said to have possessed wooden dentures, which is only half true: He had a variety of false teeth, but none of them made of wood.

Calvin Coolidge is said to have been approached by a fellow who had bet he could get the famously withdrawn president to say more than two words, to which Coolidge allegedly responded: “You lose.” Coolidge denied the story ever happened, but “Silent Cal’s” famously laconic style has kept it alive for a century.

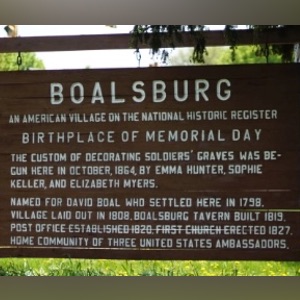

Meanwhile, at least two U.S. towns attempt to lay claim to being the birthplace of Memorial Day—including Boalsburg, a small, unassuming community about 90 minutes northwest of Harrisburg.

The town is not shy about claiming the mantle, touting itself on its website as the “birthplace of Memorial Day.” It’s not hard to understand why a place would like to boast that designation. Memorial Day is arguably the most hallowed U.S. national holiday, a day when we honor the brave men and women of the country who gave what Abraham Lincoln called the “last full measure of devotion” in service to the United States, its values and its people.

Boalsburg leans into its history. Its official Memorial Day Festival runs a full five days, from Thursday to Monday. The celebration features “food, music and craft vendors complete with two Civil War battle re-enactments,” as well as a solemn service, a charity run, a parade, a carnival,” and more.”

So, how does Boalsburg justify its claim to Memorial Day fame? According to the town, the story “began with a lovely young teenage girl,” as many great stories often do.

In October 1864, as the Civil War was moving toward its conclusion, Emma Hunter “gathered some garden flowers” with her friend Sophie Keller “to place them on the grave of [Emma’s] father, Dr. Reuben Hunter,” who had served in the Union Army. Another local woman, Elizabeth Meyer, “chose to scatter flowers on the grave of her son Amos.”

The women, the town claims, “were participating in their first Memorial Day service.” That observance led to a yearly tradition of grave decoration, with mourners and respectful residents meeting every May to place flowers on the graves of veterans. In 1868, General John A. Logan, commander-in-chief of the veterans’ organization, the Grand Army of the Republic, declared May 30 to be “Decoration Day,” making national what had previously been local to Boalsburg.

Whether or not Boalsburg can truly be said to be the birthplace of Memorial Day depends upon some subtle but notable distinctions. Another town, Waterloo, N.Y., was declared by President Lyndon B. Johnson to be the true birthplace of Memorial Day since that town was celebrating the observance in 1866.

Resolving the dispute depends on how you classify an “observance” of a holiday. If a townwide celebration counts, then Waterloo arguably takes the prize; if a more loosely affiliated (yet still distinct) coalition of citizens is what counts, then Boalsburg is the true originator of the holiday.

Ultimately, of course, it doesn’t really matter. Memorial Day is not about competitions between municipalities (even if certain historical designations are good for business). It is about honoring the dead—the Americans who gave their lives for us, our country, and our way of life. The holiday is meant for us, the living, to reflect upon what it means to, in Lincoln’s words, “have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of freedom.”

Logan himself, in making his proclamation, urged a spirit of national unity in honor of the glorious dead, imploring Americans to observe the holiday “that it will be kept up from year to year” and that we might “gather around their sacred remains and garland the passionless mounds above them with choicest flowers of springtime,” and “raise above them the dear old flag they saved from dishonor.”

It is a good mandate and one we should follow every May. Memorial Day’s origins might be unclear, but its ultimate purpose is as vital today as it was when, and wherever, it was first founded.