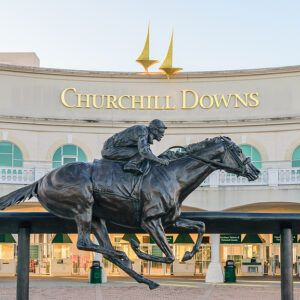

For an opposing point of view see: “Counterpoint: Celebrate Derby Day!” The first Saturday in May has been a day of mourning since 2008, when Eight Belles broke both front ankles after crossing the finish line in the Kentucky Derby. She was euthanized on the track. America had fallen out of love with horse racing years before, […]