Ira Einhorn: Philly Counterculture Icon, Earth Day Organizer, and Killer

It was 43 years ago when Mike Chitwood arrested Ira Einhorn for murder in the death of his girlfriend, Helen “Holly” Maddux. But he remembers it vividly.

Chitwood, then a Philadelphia homicide detective, had obtained an extensive search warrant for Einhorn’s second-floor apartment in 1979, to look for physical evidence that would show Einhorn killed Maddux, Chitwood told the Delaware Valley Journal.

Einhorn, known as the “The Unicorn Killer” because of the English translation of his last name, was a 1960s counterculture guru who dabbled in LSD and taught at the University of Pennsylvania. An environmental activist, he also claimed to have come up with the idea for Earth Day. Most historians give that credit to the late Sen. Gaylord Nelson (D-Wisc.).

After Philadelphia Police failed to arrest anyone in Maddux’s 1977 disappearance, her family hired a retired FBI agent, who teamed up with another retired agent. Their investigation led to Einhorn, but they needed to work with the police to make an arrest.

That was when Chitwood got involved.

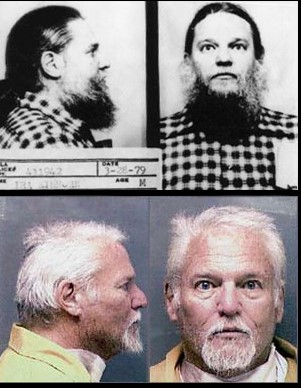

Ira Einhorn mugshots 1979 and 2002 (Wikipedia)

“I took the (agents’ murder) booklet and I read it that night and I thought to myself, ‘I know who killed her.’”

“I reinterviewed everybody in the booklet and eventually interviewed a guy named Saul Lapidius, who was apparently a wealthy guy. He had a boat out on Fire Island (N.Y.) and Holly was staying there. She had left Einhorn after five years.”

But Einhorn called Maddux and told her if she did not return for her clothing and other belongings he would burn them. So she came back to Philadelphia. While she was there, Maddux and Einhorn went to a movie with another couple. When they got back to his apartment they argued and “he killed her.”

“He beats her to death, crushes her skull…He doesn’t know what to do. So he eventually puts the body in a steamer trunk and puts the trunk in a closet that’s on an outdoor porch.”

“At one time he tried to take the trunk out but he was so paranoid of the federal government, he just couldn’t do it,” said Chitwood. Einhorn believed he was under investigation because of his friendship with 60s radical activists Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin.

Maddux, who grew up in Texas, had graduated from Bryn Mawr. She was only 30 when she died and by all accounts a beautiful woman, said Chitwood.

Holly Maddux

The downstairs neighbors had heard a loud noise the night Maddux disappeared and later they complained to the landlord of a bad smell and fluids leaking through their wall, Chitwood said.

But Einhorn, who told police that Maddux had left to get groceries and never returned, was not arrested until Chitwood found Maddux’s body in that trunk.

When Chitwood and other cops got there, Einhorn’s apartment was dirty and in disarray. He was bearded and wearing only a robe when detectives arrived. The balcony closet was stuffed full of boxes, some with Maddux’s clothing. And when Chitwood saw her ID cards, he became even more suspicious because “no women I’ve ever investigated or been involved with ever left everything behind.”

At the very bottom of the closet was a locked steamer trunk.

Chitwood broke into the trunk with a crowbar, preserving the lock, and there were plastic bags and copies of the Evening Bulletin from 1977.

“You could smell the body,” he said. “I didn’t know the body was still in the trunk. I figured it was at one point in time. I came across a layer of foam and then I gingerly, slowly but surely, started removing the foam.”

“And there was a hand, a mummified hand,” said Chitwood. At that point, he stopped and called for the medical examiner.

Chitwood said to Einhorn, who had been watching, “It looks like we found Holly.”

“You found what you found,” Einhorn said to him and walked back into the apartment and was subsequently arrested.

Mike Chitwood

The late Arlen Specter, who had been district attorney and would go on to become a U.S. senator, was working as a defense lawyer at that time and represented Einhorn. Although Einhorn was charged with first-degree murder, Judge Armand Della Porta set bail at only 10 percent of $40,000 and Einhorn easily paid the $4,000 and walked out of jail. Many rich and influential people wrote letters to the judge on his behalf, said Chitwood. Several accounts describe Einhorn as charming and charismatic.

Asked about Einhorn’s purported charisma, Chitwood said, “He certainly had something. He got out with accolades from different people in the business community who talked about what a wonderful person he was…the letters people wrote. It was not an array of misfits. It was affluent people.”

Once free on bail, Einhorn disappeared.

There were sightings all over, from Thailand to Europe. Finally, 20 years later, Einhorn was found in France, married to a wealthy Swedish heiress and living in a converted windmill. He was extradited to face trial in Philadelphia. Lynn Abraham was the judge who signed the original search warrant, said Chitwood. When Einhorn was brought back, she was the district attorney.

Einhorn was tried in absentia and convicted in 1993. Pennsylvania’s legislature passed a law that he would not face the death penalty and to allow him to be tried again since the French courts did not recognize trials in absentia.

“In no time at all he was convicted,” said Chitwood, who had testified in both trials. Two women testified about previous instances where Einhorn engaged in domestic violence, said Chitwood. One Einhorn hit with a bottle, the other he nearly choked to death. “So he had a history of domestic violence,” said Chitwood.

People believe Einhorn founded Earth Day, said Chitwood, though records only show he was the master of ceremonies at the first Earth Day event.

“I’m not saying anything good about him,” said Chitwood. “To me, he was a conman. But people believed everything he said was the gospel truth. But he was a conman and a murderer.

“All these people protected him and wanted him to be the good guy. He wasn’t that guy. What I’m saying is he was a creep and a bull-s—-er,” Chitwood said.

Chitwood was sorry Maddux’s parents never saw justice. Her father had committed suicide and her mother died of an illness during the time Einhorn was on the lam. But the family did win a $907 million wrongful death suit against Einhorn.

Einhorn was convicted the second time in 2002 and sentenced to life in prison. He died behind bars at age 79 in 2020. Joel Rosen prosecuted Einhorn both times. Ironically, if he had reported Maddox’s death to authorities and pleaded guilty in 1979, Einhorn would probably have been sentenced to only five or six years for the crime of passion, said Chitwood.

It was the most famous case in Chitwood’s long career in law enforcement.

“I mean here you are, still writing something on it,” he said. “It’s been a part of my life forever and a day.”

Follow us on social media: Twitter: @DV_Journal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJournal