KADISHA: Recognizing Veteran Homelessness in Military Appreciation Month

As we recognize those who serve our nation during this Military Appreciation Month, we must also focus on a longstanding issue demanding urgent action: the scourge of veteran homelessness. Amid the parades and tributes, including on Armed Forces Day (on May 18), we must confront the reality that those who have served are disproportionately affected by homelessness.

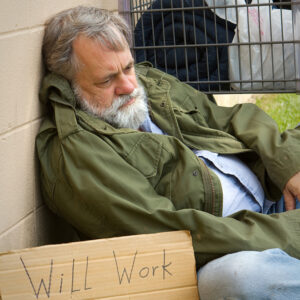

Veterans, the individuals who bravely defended our freedoms, too often find themselves among the homeless population. Studies have shown that veterans are significantly more likely to experience homelessness than other demographics. These men and women who have sacrificed so much should never find themselves without a stable place to call home. However, all too often, they do.

Homeless people are more than just statistics. These are mothers shielding children from the elements, veterans haunted by unseen battles, and individuals fighting addiction. How did we allow so many people to be forgotten and their needs ignored?

Combatting veteran homelessness requires an approach that tackles the root causes of the issue and provides comprehensive support to those in need. Support programs offered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Department of Veterans Affairs are effective in helping veterans secure stable housing. However, there is much more we can do.

While the government continues to invest in affordable housing initiatives, works to strengthen mental health services, and creates pathways to employment, the private sector must also play a role and contribute to these efforts. It’s not enough for the private sector to offer applause; it must also offer innovative solutions, flexible housing models, and job opportunities for those reentering the workforce.

Veterans often face many challenges upon returning to civilian life, including physical and mental health issues, difficulties finding employment, and a lack of access to housing. To combat veteran homelessness effectively, we must prioritize access to affordable housing. Housing is a basic human need. Property managers and real estate investors recognize their roles in this effort. They are proud to assist veterans, including those facing adversity, in finding homes. However, this is just one piece of the puzzle.

In addition to housing, addressing the underlying factors contributing to veteran homelessness requires a holistic approach to providing support services. This includes access to healthcare, mental health counseling, substance abuse treatment, and employment assistance. By addressing the comprehensive needs of veterans, we can help them reintegrate into society and lead fulfilling lives.

Preventing veteran homelessness before it occurs is another crucial aspect. Early intervention and support for veterans who may be at risk of becoming homeless are essential. Programs that provide targeted assistance to veterans in need can help prevent homelessness before it escalates into a crisis.

Addressing the stigma surrounding mental health and seeking help is also essential. Many veterans may be reluctant to seek support for mental health issues due to fear of judgment or perceived weakness. By promoting awareness and destigmatizing mental health treatment, we can encourage more veterans to seek the help they need and deserve.

Community organizations, nonprofits, and local governments also play critical roles in combatting veteran homelessness. Collaboration and partnership between government agencies, service providers, and community organizations are essential for maximizing resources and coordinating efforts to address veterans’ needs.

Ultimately, combatting veteran homelessness requires a collective effort and unwavering commitment. It is not a matter of providing housing; it is about ensuring every veteran has the support and resources needed to rebuild lives. By coming together and taking decisive action, we can honor the service and sacrifice of veterans and ensure they never face homelessness alone. We need to walk the talk — and stop walking past what makes us uncomfortable to see.

As we express our gratitude to our veterans during Military Appreciation Month, let’s commit to tangible actions that will make a difference in their lives. We can honor their service and uphold our shared commitment to leaving no veteran behind.