STELLE: Senate Higher Education Proposal is a Step in the Right Direction

A lot of bad plans on how to make higher education affordable exist. There is Gov. Josh Shapiro’s vague “blueprint,” which lacks any substantive details. Even worse is President Joe Biden’s efforts to forgive student debt, which won’t even touch rising tuition.

“Grow PA” isn’t one of those plans, though.

Pennsylvania Sens. Scott Martin, Ryan Aument, David Argall, and Tracy Pennycuick introduced the new “Grow PA” higher education reform proposal to deal with an uncomfortable fact: Pennsylvania has a shrinking population. They see making our higher education system “more competitive” as one pivotal step to reversing the exodus.

From nursing to construction, Pennsylvania industries face worker shortages with no end in sight. One analysis estimated a shortage of 278,000 nursing support professionals in Pennsylvania by 2026. Grow PA’s refreshing approach would boost aid for high-growth career pathways, attracting students to certifications and degrees that offer genuine employment opportunities.

Moreover, Grow PA grant recipients would, upon graduation, work in the commonwealth. This requisite attempts to mitigate the brain drain the commonwealth has endured for nearly two decades. By encouraging both in- and out-of-state students to study and stay, Pennsylvania could begin to address its severe worker shortage.

The current system of higher education funding—driven by politics—does not serve students or taxpayers well. Every year, lobbying and political posturing channel subsidies to schools like Penn State and Pitt, with most funding going to institutions rather than students.

Instead, our taxpayer dollars should follow students. Moving all state aid to grants administered by the Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency (PHEAA) puts students first. Students can use their grants to shop around Pennsylvania’s community colleges, universities, and trade schools. This way, schools would be more inclined to offer students the best-valued product, rather than using student aid as a slush fund for ongoing construction and administrative overhead.

While Grow PA is a step in the right direction for higher education, lawmakers should not forget that reforming and improving the K–12 funding pipeline is paramount to ensuring high school graduates are ready for college rigor, which, ultimately, would make it more affordable for them.

Increasingly, students leave high school unprepared for college-level coursework. Only one in five students in the class of 2023 graduated ready for introductory classes. Pennsylvania high school students rank 30th nationally in SAT scores.

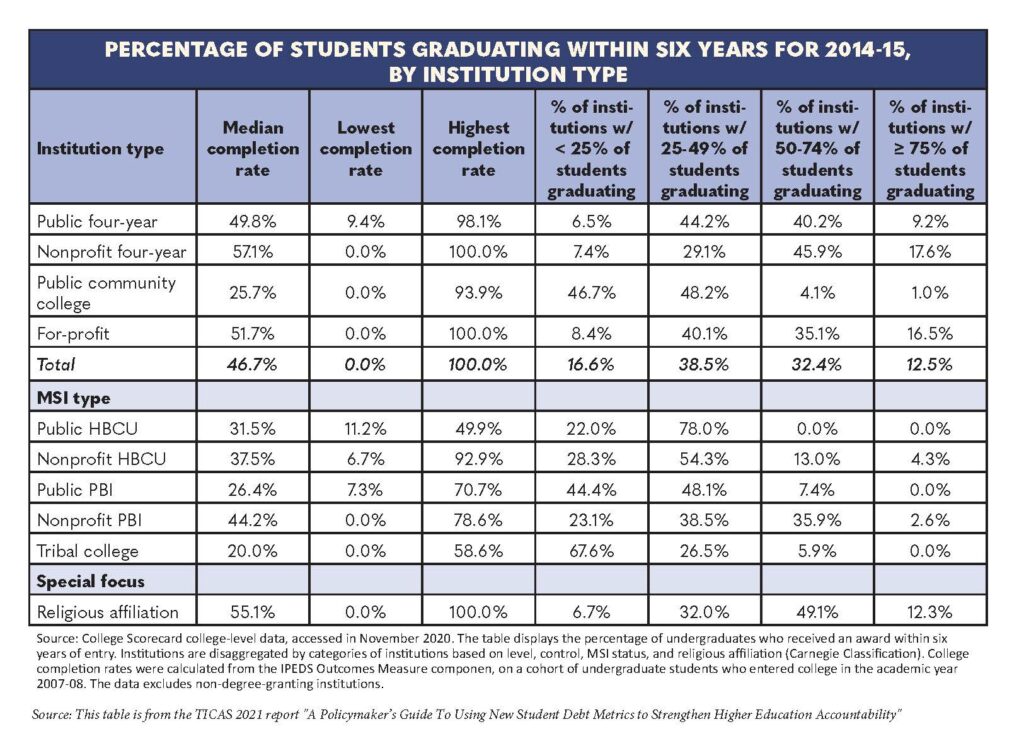

As a result, more students must enroll in remedial classes when entering college. This unsavory pattern shifts the financial burden from the schools that failed to teach them to the students who must now pay tuition for remedial coursework, potentially prolonging their enrollment and extending their stay beyond the traditional four-year timeframe. Many Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education (PASSHE) schools and state-related schools lag behind the national four-year graduation rate of 46.6 percent.

To prepare students for college-level coursework, students need a robust educational ecosystem of elementary and secondary schools. Just like competition between universities improves the value of higher education, more choices for K–12 education will help kids find a school where they can thrive academically.

To grow educational choice, lawmakers must protect and expand existing programs, such as Pennsylvania’s two tax credit scholarship programs, or adopt new ones, such as the Lifeline Scholarship Program (also known as the Pennsylvania Award for Student Success). These programs ensure funding follows students.

Moreover, what good is a degree or certificate in a lackluster job market?

A Commonwealth Foundation poll found that more than half of Pennsylvanians 30 years and younger have considered leaving the state, know somebody thinking about leaving, or know someone who has already left. Nearly three out of four exiting Pennsylvanians are younger than 65.

By reforming the commonwealth’s excessive regulatory environment, Pennsylvania lawmakers can transform our economy. Reducing Pennsylvania regulatory red tape by 36 percent would increase the state’s gross domestic product by $9.2 billion a year and create a vibrant marketplace for newly graduated students.

Yes, fixing higher education—bolstering competition and accountability—is necessary to help break Pennsylvania’s decades-long cycle of bleeding talent. Yet, there’s so much more our lawmakers need to get right to keep and attract talent to the Keystone State.

Please follow DVJournal on social media: Twitter@DVJournal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJournal