HOLY COW! HISTORY: Another Ex-President’s Brush With the Law

The airwaves are consumed with talk of former president Donald Trump’s possible arrest. Seventy years ago, another ex-chief executive had an encounter with a cop. Though the two situations were far from similar, it’s worth revisiting.

You’ve just wrapped up the world’s most demanding job. You used the atomic bomb for the first time, helped create the United Nations, and stood up to communist aggression in Korea. What do you do next?

You hit the road, of course.

Except for being a politician, Harry Truman was one of us. A down-to-earth middle-class guy who struggled to pay his bills, cherished his wife and daughter, and enjoyed a snort of Kentucky bourbon and a friendly game of poker.

And like many of us, Harry loved cars. He especially had a thing for Chrysler products.

When folks at the Chrysler Corp. heard about Harry’s remarkable customer loyalty, they gave him a new 1953 Chrysler New Yorker in appreciation. (Believing a former president shouldn’t be beholden to a corporate giant, Harry insisted on paying $1 so it wouldn’t be a gift.)

That big, shiny sedan had Harry itching to hit the road, and he knew just how to persuade wife Bess to go with him. They could drive it to visit their daughter Margaret in New York City. What mom could say no to that?

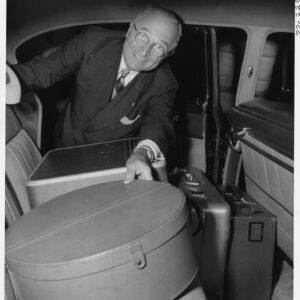

Harry was up at his usual 5:30 a.m. on Friday, June 19, 1953, at their Independence, Mo., home. Not long after sunrise, he loaded 11 suitcases into the trunk, scooped Bess into the passenger seat, and headed east. There were no Secret Service agents tagging along (they wouldn’t be assigned to ex-presidents until after JFK’s assassination a decade later). Just a former president, a former first lady, a full tank of gas, and highway maps in the glove compartment.

They were like any married couple on the road. Harry had a lead foot, Bess scolded him to slow down, and he silently fumed. (It must have been hard for a guy who had negotiated with Churchill and Stalin to have the Missus constantly harping to drive slower.)

The first stop was a diner in Hannibal, Mo., where they had fruit plates and iced tea. Congress wouldn’t grant former presidents a pension for several years, so Harry had to count pennies. They were no-frills travelers anyway. In Indianapolis, they spent the night with friends. Imagine young Claire McKinney’s surprise when trying to tiptoe inside without getting caught after staying out late she found Harry playing the family piano in the living room.

Harry and Bess went whole hog at Princess Restaurant in Frostburg, Md. —two chicken dinners for $1.40, plus tip. When word got out that the Trumans were eating there (a plaque now marks their booth), the place quickly filled up. Harry later said, “I had been there before, but in those days they didn’t make such a fuss over me. I was just a senator then.”

Stopping at a gas station for a fill-up and a soft drink, the owner asked him to give his mechanic a hard time for being a Republican. Harry replied, “It’s too hot to give anybody hell.”

His return to Washington, where Harry was finally a private citizen again after 18 years as senator, vice president and president, was a triumph.

It was nothing compared to the Big Apple. Harry and Bess painted the town red. A suite at the Waldorf Towers, two Broadway shows, and even dinner at trendy nightclub 21, where the maître d’hôtel pulled off a geographic miracle by seating them far away from Gov. Thomas Dewey, the man Truman had kept out of the White House.

The trip’s highlight came on July 5 on the Pennsylvania Turnpike. Harry was for once obeying Bess’ scolding and driving 55 miles per hour, her preferred speed. The problem was the Turnpike’s speed limit was higher, and Harry was poking along in the left lane, forcing a line of cars to build up behind him.

Without knowing who was driving, state trooper Manley Stampler motioned for Harry to pull over. (Pennsylvania’s state cop cars didn’t have flashing lights at the time.) Imagine Stampler’s shock when he saw who was behind the wheel. He recalled, “I told him what he had done wrong and he said he didn’t realize it — that it wasn’t intentional. Then, I told him how dangerous the turnpike is and … wouldn’t he please be more careful. He was very nice about it and promised to be more careful.”

Bess chimed in, saying, “Don’t worry, Trooper, I’ll watch him.” Stampler added the two-minute encounter “seemed to last a long time.”

The press found out about it and had a field day. Harry shrugged it off, claiming the trooper pulled him over just to shake hands.

Nineteen days and 2,500 miles later, the trip ended where it began. Once again, Harry carried all 11 suitcases inside himself. A simple reminder of a different time and a different type of president that we’ll likely never see again.

Please follow DVJournal on social media: Twitter@DVJournal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJournal