HOLY COW! HISTORY: Washington, Napoleon, and An Unlucky British General

Ridley Scott’s biopic ‘Napoleon’ topped the global box office over the Thanksgiving weekend. But some moviegoing history lovers are trashing it for playing fast and loose with the facts. “Disappointing” is the most charitable response from their ranks, and that’s putting it mildly.

The flick’s faults aside, the current ‘Napoleon’ buzz makes this the ideal time to recall the story of a spectacularly unlucky British general who had an unfortunate encounter with the Little Corporal—and with the Father of Our Country as well.

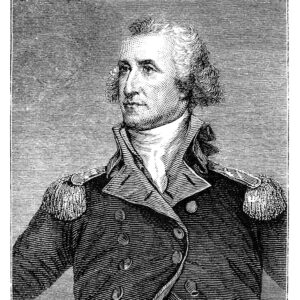

Charles O’Hara began life under a cloud. He was born out of wedlock in 1740. That may not sound like a big deal today, but it was hugely problematic to the aristocratic crowd that ran Georgian England. His father, a dashing army officer whose star was rising, accepted the boy and made sure he followed in the old man’s military footsteps.

O’Hara entered the army when he was 12 (a not uncommon age at the time) and quickly began his own ascent up the command ladder. He was a strict disciplinarian but popular with his troops despite it. When Daddy became a field marshal in 1763, his connections helped O’Hara rise up the ranks with lightning speed.

By the end of the American Revolutionary War, O’Hara was a brigadier general serving in the South under Lord Cornwallis. Severely wounded in the battle of Guildford Courthouse in North Carolina, he nevertheless accompanied the British army to Virginia — only to be trapped by the American army and the French navy in the Siege of Yorktown.

When the Brits were finally forced to give up, Cornwallis refused to do his duty and attend the October 19, 1781 surrender ceremony. Pleading illness, he foisted the unpleasant job onto O’Hara.

O’Hara then tried to get in his own parting dig against the Americans. When it came time to formally surrender his sword, he handed it to the Comte de Rochambeau. But the French commander deferred to General George Washington, who then made O’Hara hand it over to General Benjamin Lincoln. That was significant because Lincoln had been forced to surrender to the British when Charleston, S.C., fell some 18 months earlier.

O’Hara’s bad luck continued back in England, where his massive gambling debts caught up with him, and he was forced to flee to the Continent to avoid his creditors. His old boss Cornwallis eventually came to his rescue, bailing him out so O’Hara could return home. But he didn’t stay there long.

As the century drew to a close, he was promoted to lieutenant general and made governor of Gibraltar. But just when it seemed O’Hara’s life was back on track, his train derailed again.

With the French Revolution in full swing, attention focused on the important port city of Toulon. The British, Prussians, Austrians, Dutch, and Spanish monarchies wanted to keep the seeds of revolution that had sent France’s king to guillotine from blowing into their countries. French fighters opposed to the revolution seized the port. The British sent soldiers led by O’Hara to support them. French Revolutionary forces were also dispatched to Toulon for a showdown.

On Sept. 8, 1793, a young, untested French officer arrived and was placed in command of the Revolutionary artillery. He devised a plan that led to the capture of a key hill, giving his guns command of the port city. There was a series of back-and-forth fighting. In the final round, O’Hara was wounded again. And once again, he was forced to surrender to the commander of the forces who inflicted defeat.

It was an obscure Corsican named Napoleon Bonaparte.

(The victory at Toulon launched Bonaparte down the path toward becoming Emperor a decade later.)

O’Hara spent two years in a Paris prison (where he was threatened with a date with Madame Guillotine) until he was finally exchanged for the Comte de Rochambeau, the same officer he had tried to surrender to at Yorktown 14 years earlier.

He fell in love and got engaged, but the relationship fell apart when he was appointed governor of Gibraltar again, and his betrothed refused to leave England. He died on the Rock from his old war wounds in 1802 at the age of 61. (Or 62. His precise age is fuzzy due to the murky circumstances surrounding his illegitimate birth.)

While his record on the battlefield was only so-so at best, Charles O’Hara holds a distinction no other officer could claim—or want: He was the only person in history to surrender to both George Washington and Napoleon Bonaparte.

Please follow DVJournal on social media: Twitter@DVJournal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJournal