Biden and Buchanan, the Two Presidents With PA Roots

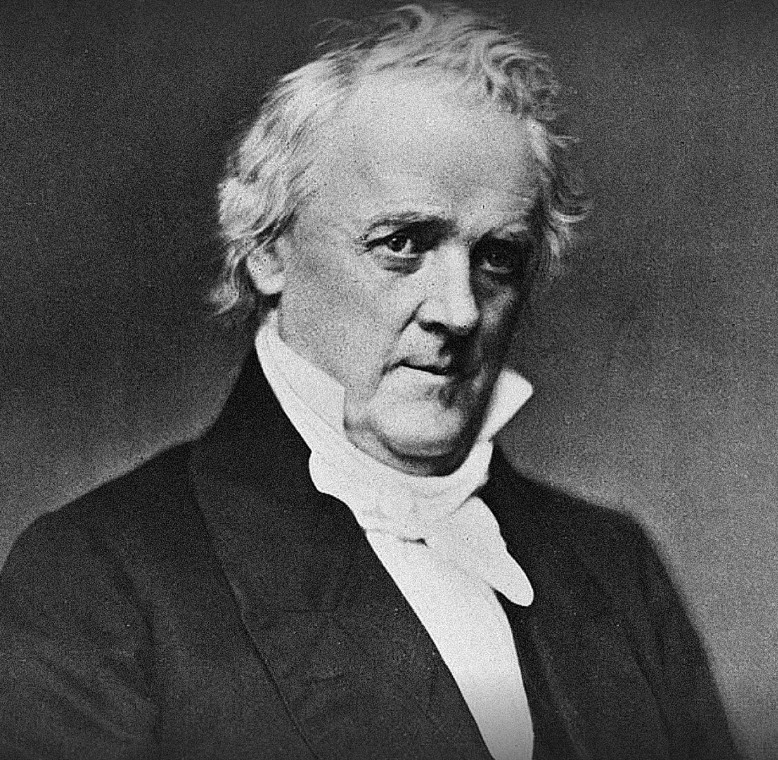

Only two presidents were born in Pennsylvania: Joe Biden and James Buchanan. And despite 160 years between the time they served, the two Democratic residents of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue have a surprising amount in common.

And that’s not necessarily good news.

First, the obvious differences: Buchanan remained a lifelong Pennsylvanian, while Biden’s family moved from Scranton to Delaware when he was 13. And Buchanan is the only bachelor to serve as president, while Biden relies heavily, according to media reports, on his wife, Dr. Jill Biden.

But they also have similarities, too. Both were senators before becoming president. Both saw their popularity wane while in office. Buchanan pledged during his campaign to only serve one term. Many voters originally believed Joe Biden was only seeking a single term as well.

“Look, I view myself as a bridge, not as anything else,” Biden said at a 2020 rally. Biden was already 77 years old at the time. Instead, he now wants to serve until 2029, at which time he would be 86 years old.

J. Mark Powell, author of the popular nationally syndicated “Holy Cow! History” column, said, “Historians often rank Buchanan as the worst president of all. And with good reason. When you allow the country to come apart on your watch, it doesn’t get any worse than that. It was the very definition of failure.”

“Apart from both being born in Pennsylvania, the closer you look at them, the more the two have in common,” said Powell. “Their last names both start with a B, both were Democrats, and both were highly unpopular presidents. Each was elected by voters who believed they would ease tensions in the country, yet divisions only deepened during their administrations. And in the final analysis, each did not live up to popular expectations.”

In fact, one notable difference is that while Buchanan failed to find common ground to bring Americans together during the debate over slavery, Biden has rejected the premise of national unity. Instead, he went to Philadelphia in 2022 to deliver a speech declaring former President Donald Trump and his “MAGA” supporters a threat to democracy. Biden said millions of Americans are “extremists” who don’t love America.

Buchanan didn’t even say that about southerners who were threatening to secede from the Union.

Arcadia University history Professor James Paradis said, “The one thing that stands out to me is the difference in attitude of the two presidents as they ended their first term. Both of them faced the problems of leading a strongly and passionately divided nation. Both of them, fairly or not, were also blamed for the economic difficulties of their times. Buchanan had to deal with the Panic of 1857 and, for Biden, a painful inflation rate.”

“With the nation splitting in two as his term approached its end, Buchanan looked forward to stepping down from the presidency. When Abraham Lincoln came to Washington to succeed him, Buchanan reportedly confided to Lincoln, ‘Sir, if you are as happy in entering the White House as I shall feel on returning to Wheatland, you are a happy man indeed,’” Paradis said.

“For Biden, on the other hand, in spite of the pressures that he faces and the lukewarm support he is receiving from his own party for reelection, his desire for reelection seems unabated,” Paradis said.

Born in 1791 near Mercersburg, Buchanan studied at Dickinson College, passed the bar, and practiced law in Lancaster. Biden graduated from Syracuse University Law School, returned to Delaware, and served on the New Castle County Council. At 29, he became one of the youngest people ever elected to the U.S. Senate.

Buchanan served in the military during the War of 1812. Biden received deferments from military service during the Vietnam War for asthma.

Buchanan was elected to the state legislature in 1814 and continued his political career in Congress, serving as a representative and then a senator.

He was ambassador to Russia and Great Britain and did a stint as secretary of state.

Buchanan ran for president without winning three times before the Democrats tapped him in 1856 because of his reputation as someone who could find common ground.

Biden also ran for president unsuccessfully in 1988 and 2008 before obtaining the office in 2020. He had served as vice president for President Barack Obama from 2009 through 2016.

Shortly after Buchanan took office, the U.S. Supreme Court issued the infamous Dred Scott decision, which upheld slavery. Despite being a northerner, Buchanan favored it. He believed slavery was morally wrong but felt the issue should be decided by the states, not the federal government.

In 1858, Congress was divided among northern and southern Democrats and Republicans. The Panic of 1857 and John Brown’s antislavery raid on a federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry added to the turmoil. Amid all the division, Abraham Lincoln led the nascent Republican Party to victory in 1860.

But, angered by Lincoln’s election, South Carolina and other states seceded from the Union and formed the Confederate States of America, leading to the Civil War.

In his final months in office, Buchanan tried to compromise with the secessionists. He remained somewhat passive, and some modern historians criticize him for not acting more firmly to quash the rebellion. However, at that time, presidents waited for Congress to weigh in rather than acting themselves, said Powell.

In a letter that is part of Powell’s collection of historical correspondence, Lewis S. Coryell, a 72-year-old successful businessman, and member of the Pennsylvania Democratic Party in New Hope, who was an active Buchanan supporter, praised him at the height of the secession crisis during Buchanan’s final 90 days in office.

Coryell wrote on Jan. 14, 1861: “Mr. Buchanan has, with a view to conciliation to avoid violence, practiced the most masterly inactivity. History will assign a proud page to his merits.” That was not to be the case.

“One last similarity remains to be seen. Buchanan was a one-term president,” said Powell. “We won’t know until November if Biden will add that to the list of things they shared.”