HOLY COW! HISTORY: Ike’s Secret Baseball Career

March Madness may bring basketball to the forefront, kids may chase soccer balls in droves, but baseball remains our national pastime. It’s woven into our country’s fabric alongside apple pie and Fourth of July fireworks displays.

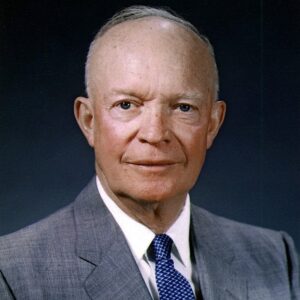

And of all our presidents, Dwight Eisenhower may have been the game’s biggest fan. He was crazy about it. The man who brought down Hitler and later gave us interstate highways was a born jock. And he was a pretty good one, too.

A typical American teenager, Eisenhower lived, breathed and ate sports while growing up in Abilene, Kan. He played center field on his high school team. His big brother Edgar played first base.

Ike was the third of six brothers. The Eisenhower boys had lots of intelligence, but the family had little money. Ike pursued an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy because it provided a free education.

Like most young men, de arrived at West Point with a heart overflowing with dreams. More than anything, he wanted to be a famous ballplayer.

Ike dutifully tried out for the varsity baseball team. But he didn’t make it. He later called it “the greatest disappointment of my life.” He also enjoyed football, and turned to it for his Plan B. He made Army’s varsity football team the following year (even playing against the legendary Jim Thorpe) until a knee injury forced him to give up the game.

Yet, not making the baseball team may have been a blessing in disguise because Ike had a potentially explosive secret. After finishing high school in 1909, he spent two years working at a creamery to help pay Edgar’s way through the University of Michigan. He also played baseball for money under an alias. Though politics was still decades off in his future, the teenage Eisenhower was already thinking like a politician by keeping his options open.

Regardless of how small the amount, taking money would have ended his amateur status. If he had made the Army team and had word of his earlier play for pay leaked out, he would have been expelled for breaking the Academy’s Honor Code. His career would have been over before it began. There would have been no Ike as commander of the D-Day invasion, no “I Like Ike” buttons, no Eisenhower in the White House. So naturally, he did his best to keep his secret hidden.

Until the end of World War II, that is. Returning to a hero’s welcome in New York City, he took in a New York Giants-Boston Red Sox game. Giants’ General Manager Mel Ott asked Eisenhower if it was true he had once played semi-pro ball. Caught up in the excitement of the moment and with reporters listening nearby, he blurted out that yes, he had played under the assumed name “Wilson,” then said it was “the one secret of his life.” (Historians would say he had another one: his wartime affair with his British military chauffeur Kay Summersby.)

The story made it into print, forcing Ike to do damage control a few days later. He told the Associated Press he had taken “any job that paid money” during his pre-college days.

But the cat was out of the bag. The book “Going Home to Glory” by Eisenhower’s grandson David recounts a story related to him by former Brooklyn Dodgers public relations man Arthur Patterson. While watching a game with Ike once, Patterson said he recalled hearing that two young men named “Wilson” had played in the Kansas Central League in 1909. Which player was Wilson, and which was Eisenhower, he asked.

“I was the Wilson who could hit,” Ike shot back. Then he quickly added, “That’s between you and me.”

In an era when presidential scandals involve payoffs to porn stars and cocaine in the White House, an illicit baseball career isn’t a biggie. And it’s easy to sympathize with Eisenhower, too. The man who led Americans into combat and through the Cold War wasn’t above cutting a few corners just to play the game we all love.

Please follow DVJournal on social media: Twitter@DVJournal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJournal