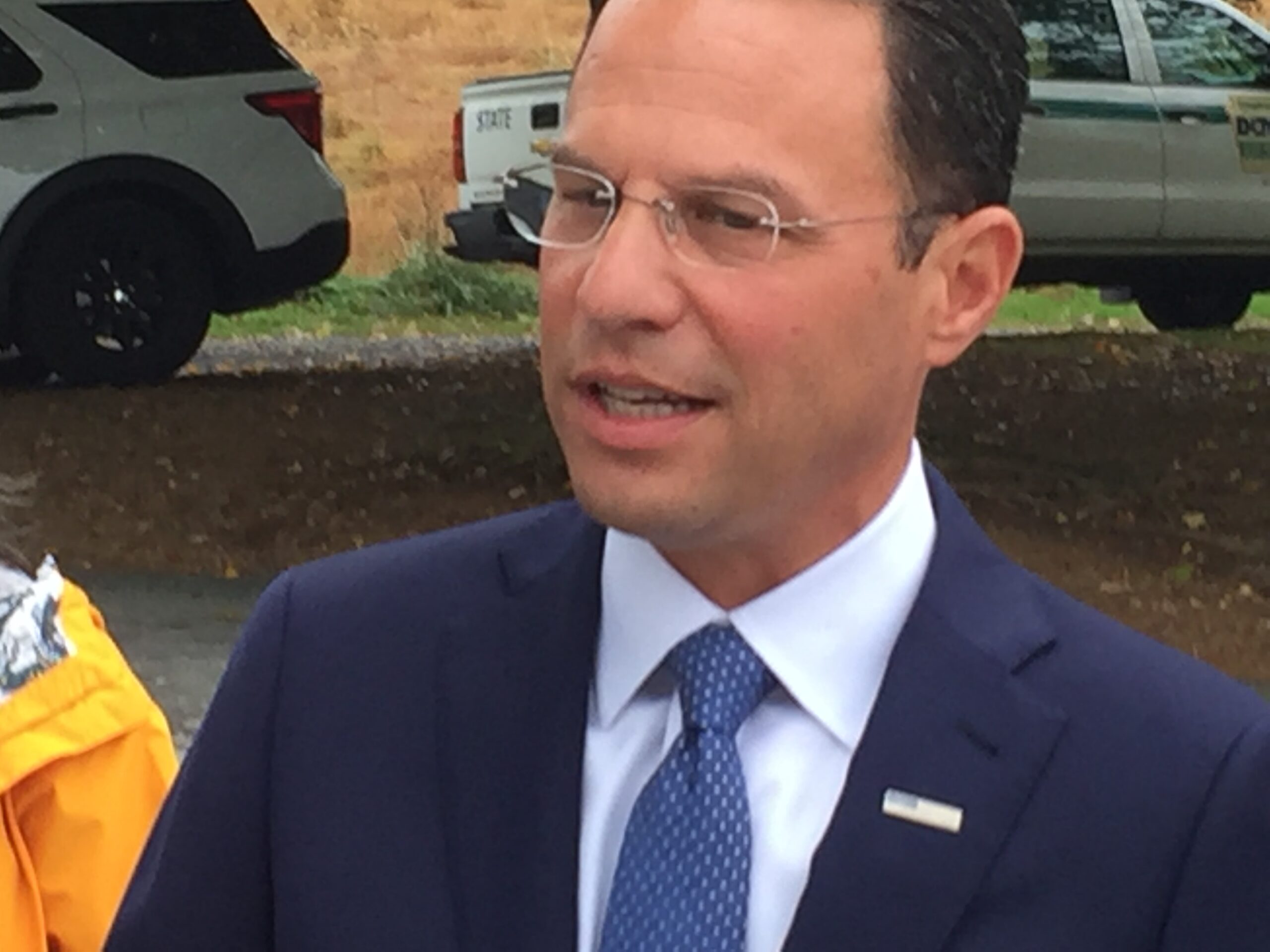

There ought to be a law that prosecutors can’t run for political office. Whenever an attorney general wants to run for governor there are, invariably, a bunch of indictments brought to raise the prosecutor’s profile. It’s non-partisan in that they all do it and, once the elections are over, the cases tend to quietly fade away. So it is that Attorney General Josh Shapiro has brought criminal indictments against Energy Transfer over Mariner East pipeline construction.

Shapiro is in the mold of Kathleen Kane, Elliot Spitzer, and Andrew Cuomo. Those names remind us of the explosive dangers in mixing arrogance, insatiable desires for power, and access to grand juries. It appears this is criminalization with an intent to further politicize. The indictments against Mariner East look to be, more than anything else, about grabbing some southeast Pennsylvania headlines and solidifying a political base.

Energy Transfer, which has a pretty darned good record in court, notes it has “been aware of the grand jury’s investigation” and has “cooperated with them and the Attorney General’s Office for several months in an effort to address and resolve any issues.” But, of course, dealing with issues isn’t the point for Shapiro.

A quick look at the indictment, in fact, reveals there is much less there than meets the eye in the press release. The grand jury admitted, in fact, that bentonite clay at the heart of complaints was approved by DEP for use “in the drilling of water wells, which presumably makes it safe for consumption if it should happen to get into a drinking supply.” They then go on to suggest there might have been unapproved additives and these might have caused a problem.

One particular case cited in the indictment includes mention of some “initial sampling and analysis that showed the presence of bentonite” in one woman’s home. That is then tied to “a follow-up email informing her that additional test results indicated her water had tested high for e-coli and fecal coliform.” How construction activity could yield fecal coliform is conveniently ignored in favor the scare value. Then, to top it off, the very political indictment offers up that “in the intervening time period, her daughter drank the water and was hospitalized.”

Bentonite is not only used in drinking water systems, but people pay to put it in their bodies to “attract and bind ‘free radicals’ and other toxins.” Shapiro simply, and not so cleverly, interjects the idea there may have been unapproved additives, they might have been dangerous and, just maybe, those e-coli and fecal coliform issues might be related, which of course they are clearly not. This is pure demagoguery and how it works when eager-beaver prosecutors are determined to fell a tree and build a political campaign.

Criminalizing environmental issues, though, is risky business, as a wise Washington Times editorial from earlier this year explained: “Fossil fuel resources that power the modern world, such as oil, natural gas and coal, have long been in the crosshairs of global-warming alarmists worried about greenhouse gas emissions. But favored renewable energy initiatives meant to save the planet also leave lasting scars upon the land.

The ground extraction of silicon, silver, and lead has soared in recent years — materials that solar panel manufacturers have fashioned into the hardware capable of producing 140 gigawatts of electricity in 2019 alone. By 2050, as many as 78 million metric tons of solar panels are expected to have reached their expiration date and will wind up in the dumpster. Recycling useful elements is expensive, so panels are routinely sent to landfills, where toxic elements can leach into water tables.

“The manufacture of batteries for zero-emission electric vehicles requires rare earth minerals such as cobalt — mined in places such as Congo, where children are sent into unsafe excavations — and lithium extracted in China, where environmental regulations are lax.”

Environmentalists in Washington and capitals around the world might scoff at the notion that their “green” revolution could be regarded with the same scorn with which they currently view carbon-fueled commerce. That is worth pondering, though.

Yes, some future AG who wants to be governor might not hesitate a bit to go after the folks who pushed the idea, subsidized it, and promoted it. What’s the saying? “What goes around, goes around?