As Philadelphia’s crime crisis makes headlines every day, fears grow that the violence will spill into the suburbs. However, two years since that crime surge first started, those fears remain unfounded. For example, homicides in Montgomery County actually declined in 2020, the most recent year for which data is available.

And despite a rise in homicides in Delaware County in 2020, crime is falling in its most-violent municipality, Chester.

With the streets of Philadelphia engaged in what sometimes appears to border on open warfare, why has the violent crime problem crossed over into the Delaware Valley suburbs? Local district attorneys say it is because preventative efforts have slowly gained favor in law enforcement.

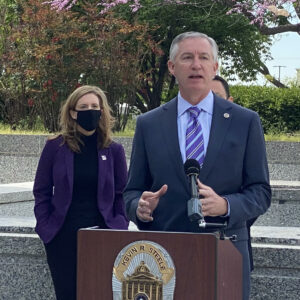

Delaware County District Attorney Jack Stollsteimer

Montgomery County District Attorney Kevin Steele is a career prosecutor who has been in law enforcement for more than 30 years. During that time, he watched law enforcement evolve from reacting to crime after it happens to proactively trying to prevent it.

“The role of a prosecutor has expanded from kind of looking back at that law-and-order type of thing,” Steele said. “I think where we’ve moved to is looking at prevention.”

Jack Stollsteimer, district attorney for Delaware County, cites the city of Chester’s fall in crime as a perfect example. He credits an initiative between the district attorney’s office and Chester’s mayor and police. The program looks to identify those who are committing crimes and then intervenes by giving them a choice.

“You go to them and you give them the opportunity to say, ‘We will help you if we can, but we will stop you if we must,’” Stollsteimer said. “You remove those people by getting them to stop killing, or you put them in jail.”

But the program does more than that. It establishes relationships within the community and involves every aspect of it as part of the effort to reduce crime. That includes the local basketball association, which helps create programming to keep kids out of trouble, Stollsteimer said.

It is all about a holistic approach to combating crime. “Everybody has a role to play in this story,” Stollsteimer explained. “It’s not even just getting law enforcement and (the) community to work together. It’s to get other government agencies, businesses.”

Steele points to Pottstown as another success. When he came into office in 2016, he said the town had a lot of unresolved shootings. The office used many different tools to eventually discover the suspects causing the violence and prosecuted them successfully. However, the story did not end there.

“We embedded a group of prosecutors in Pottstown to work with the police, with community leaders, with schools, with elected officials,” Steele said. These ‘community justice’ units stayed after the crime was solved to work to rebuild. “Now, if you look at a community like Pottstown, you hear about economic development, about the rising prices for housing in the area. It’s an area to go after.”

Despite the good news, Steele said Montgomery County still has problems. Those most important to him involve the preservation of life: Overdoses, violent crime, domestic violence, and child abuse.

On overdoses, Steele supports initiatives like drug take-back days to get pills out of medicine cabinets, where they might be readily available to addicts. There’s also a year-round effort like take-back boxes in every police department. And having Narcan in every police car to treat overdoses immediately can also prevent deaths.

With overdose deaths in Montgomery County falling last year even as ODs rose nationally, Steele sees evidence these efforts are paying off.

Guns remain the biggest issue in violent crime and straw purchasers–those who purchase firearms for others who legally cannot–are one of Steele’s greatest concerns. It is why Montgomery County is working collaboratively with neighboring counties to go after these purchasers, trying to get those guns back before they can be used in other crimes.

Montgomery County has a close relationship with local victim agencies, like the Laurel House, a domestic violence shelter, and Mission Kids, a child advocacy center. They work with experts collaboratively to prevent abuse while also accommodating crime victims.

“The saves are hard to quantify,” he said. “But if you look at what’s going on around us, and the direction that other places are going that aren’t doing the things that we’re doing, I think that that’s a very important thing to look at.”

In Delaware County, Stollsteimer said challenges depend on the specific community. There is an increase in car thefts in more affluent Swarthmore, but violent crime appears to be rising in Upper Darby.

Some of it may be due to a spillover from Philadelphia, Stollsteimer said, with many Delaware County municipalities bordering the city. However, years of neglect and rises in poverty in some areas may also play a role.

“There are people who have been predicting now for a generation if you don’t invest in the housing stock and businesses (in the first generation suburbs),” he said. “You’re going to see the same problems you’re seeing in urban neighborhoods.”

But initiatives like that of Chester may be the guide to successfully turning back the tide.

“The roadmap is there,” Stollsteimer said. “We just have to follow the plan.”

Delaware County also has not been shy about criminal justice reforms similar to those blamed on the increase in Philly crime since progressive District Attorney Larry Krasner took office.

Stollsteimer supported the de-privatization of the county prison and recently started a central arraignment process involving his office, the courts, and public defenders, where bails are actively reviewed. And defendants are given access to lawyers early in the process.

His office last year also created a program with state Attorney General Josh Shapiro known as the Law Enforcement Treatment Initiative, where individuals can contact law enforcement to seek treatment for addictions without any fear of prosecution or arrest.

Stollsteimer called that a more long-term investment than policy changes, but says he hopes it will allow the office to help communities more.

“If we have only the maximum number of people incarcerated for as long as required for the conditions of justice, then we can use some of those savings to reinvest in people,” he said, about not solely relying on incarceration.

But the most important key to success, said Steele, is the level of trust his office has built between residents and law enforcement.

“That’s earned. You can’t just say, ‘trust me,’” Steele said. “You have to earn it, every day. And you earn it by making a difference in people’s lives.”

Please follow DVJournal on social media: Twitter@DVJournal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJourn