This article first appeared in Broad + Liberty.

A Commonwealth Court ruling on Tuesday will likely erase previous restrictions that had kept citizens, journalists, and some public officials from being able to access autopsy reports in the largest counties in Pennsylvania.

A quirk in the state’s Right-to-Know Law, combined with another piece of legislation known as the Coroner’s Act, created a scheme in which anyone could get an autopsy report in counties of the third class or lower. Counties of the second or first class, however, had the legal ability to deny access to those documents.

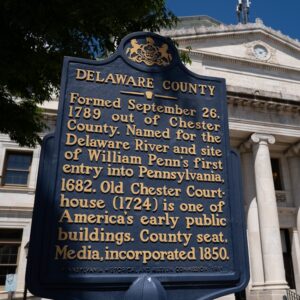

The 6–1 ruling seems likely to shake loose a key document in Delaware County, where officials have thus far denied access to the autopsy report for an inmate who died at the county prison last February of what officials described as a “delayed homicide.”

“The homicide is a delayed homicide from complications from a previous gunshot,” county spokeswoman Adrienne Marofsky said in March, roughly one month after inmate Mustaffa Jackson died.

Broad + Liberty filed a Right-to-Know request for Mustaffa Jackson’s autopsy to learn more, given that county officials have not divulged any of the most basic information about his death, including when and where he was originally shot, and the degree to which that wound received appropriate attention while he was incarcerated.

After county officials denied the request, Broad + Liberty appealed that decision to the Office of Open Records. The appeal is still pending.

If the autopsy is ultimately pried loose, it will be due to today’s ruling borne of similar problems at the Allegheny County prison that emerged in 2020, where Delaware County’s new warden, Laura Williams, was then serving as a deputy warden.

The lack of transparency in obtaining an autopsy for a prisoner who died under extraordinary circumstances spurred one reporter in Pittsburgh to fight the issue all the way to Commonwealth Court, which generated today’s ruling.

As Pennsylvania law stood just one day ago, counties of the third class or lower have coroners who must file their autopsies yearly with the county prothonotary. When that happens, the documents essentially become public records.

In counties of the first and second classes, however, coroners are replaced by medical examiners who are not required to make the same filing with the county court system that lower counties are. As a result, medical examiners in larger counties like Philadelphia, Allegheny, and Delaware could keep autopsies closeted.

In 2020, Allegheny County Jail inmate Daniel Pastorek died under unusual circumstances that journalist Brittany Hailer was determined to verify.

“Two incarcerated people who were housed with Pastorek in the acute mental health housing unit told [the Pittsburgh Institute for Nonprofit Journalism] that Pastorek cried out for medical attention for days,” Hailer wrote. “He complained of chest pains, vomited, and seemed disoriented, incarcerated persons said. They remembered him as the elderly man with the walker. One man said he was haunted by Daniel’s death, and said he felt like he was watching himself die on the floor of the cell.”

The attempts to obtain Pastorek’s autopsy have been something of a legal ping pong match.

Hailer’s Right-to-Know request for Pastorek’s autopsy was denied, but the denial was then reversed on appeal at the Office of Open Records. Allegheny County then elevated the matter to trial court where a judge reversed the OOR.

With the help of the Reporter’s Committee for Freedom of the Press, Hailer appealed that last decision to the Commonwealth Court, which heard oral arguments on the case in May.

The judges in the majority said counties of the second class or higher, like Allegheny and Philadelphia, were essentially taking advantage of a wording quirk when the Pennsylvania General Assembly made some minor updates to the Coroner’s Law in 2018.

“Accepting the conclusions of the trial court would lead to the absurd result that a requester could receive autopsy records located anywhere in the Commonwealth, unless those records are located in [Allegheny County] or Philadelphia County,” the majority noted in Tuesday’s opinion.

Even before Tuesday’s result, the challenge was catching the eye of transparency advocates.

“Government accountability depends on a favorable ruling for PINJ. It’s highly unlikely that a bitterly divided state Legislature would fix the problem by cleaning up the law,” the Pittsburgh-Post Gazette wrote in a house editorial.

“Making autopsy records public in some counties but not others is absurd. It amounts to access by geography. If anything, the right of public access is more compelling in larger counties, where more deaths occur.”

The death of Mustaffa Jackson has already been kept behind a veil by Delaware County administrators. Like Pastorek, Mustaffa Jackson does not appear to have any kin, close or far, advocating on his behalf — and who might have legal access to the autopsy because of the family relations.

Towards the conclusion of the Post-Gazette piece, the paper seemed to speak to the driving reason behind Broad + Liberty’s request for the autopsy of Mustaffa Jackson.

“The cause of the deceased’s death, without additional information, reveals little about the circumstances leading to it. If a person dies of a shotgun wound, for example, it matters greatly whether the wound was in the chest or in the back. Autopsy records are important pieces of the puzzle in determining how someone died, and whether the death was preventable.”

The final determination from the Office of Open Records on the Broad + Liberty appeal for the autopsy is due on or before next Monday, July 17, which now seems likely to incorporate new conclusions based on the Tuesday ruling.