The U-boat skipper stared through his periscope through the murky September waters of the North Atlantic. He smiled at what he saw. It was the prize every sub in a German Wolf Pack dreamed of stumbling upon: an unprotected British convoy.

Spotting those ships set in motion a chain of events that included an invention enabling people to read this story online right now.

But first, the backstory.

Britain was reeling from the Nazi Blitz in 1940. Adolf Hitler hoped to pound his adversary into submission as his Luftwaffe rained a blizzard of bombs on neighborhoods night after night.

As civilian casualties mounted, pressure grew for Prime Minister Winston Churchill to protect England’s children. With their homes now a battleground, the only way to safeguard them was to send them far away.

The Children’s Overseas Reception Board was created to ship kids to safety. In all, 2,664 youngsters were relocated to host homes in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the United States.

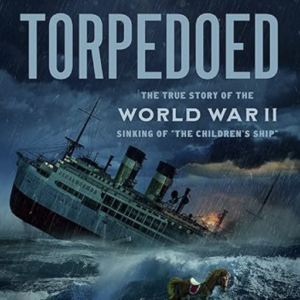

That was why the 408 people onboard the passenger liner S.S. City of Benares included 123 children age 2 to 15. It was heading for Montreal, Canada, where the youngsters would wait until peace returned.

The trip was ill-fated from the start. German planes had mined the Mersey docks, delaying the convoy’s departure until the waterway was cleared. Sailors, always highly superstitious, were troubled that the voyage began on Friday, Sept. 13, 1940.

Because of the delay, the British warships assigned to protect the convoy couldn’t escort it on the entire journey. They were on a strict deadline and had to turn back on Sept. 17 to meet up with a second convoy, as planned.

The City of Benares and 18 other merchant vessels steamed on, totally unprotected, pressing ahead through a Force 6 gale.

With the weather growing worse by the hour, the children’s after-dinner on-deck activities were canceled. However, there was good news. The ships had reached a point where it was thought the Wolf Packs were incapable of operating, so safety measures were relaxed. They now didn’t have to sleep in their daytime clothes and could skip wearing their bulky life vests in bed.

When the U-48 spotted the convoy, Korvettenkapitan Heinrich Bleichrodt waited until the lead ship, which was the City of Benares, came into attack range. He had no idea 155 women and children were aboard. Because she had been painted wartime gray, Bleichrodt thought it was carrying cargo for sale in the United States.

The children were put to bed at 8 p.m. as the storm picked up. The first two torpedoes were fired at 10 p.m. Both missed, and the ship’s lookouts spotted them. But with winds now howling at Force 10 level, the strongest measurement, there was little the captain could do.

Below the waves, Bleichrodt didn’t want to give up the easy pickings. He fired a third torpedo at 10:01. It struck the bow two minutes later, detonating just below the children’s quarters.

The ship rapidly took on water. One girl, who incredibly had survived a previous U-boat attack on another ship, reportedly said, “Fancy that! It’s happened again!”

It was one of World World War II’s worst maritime tragedies. The U-boat’s blinding searchlight swept the decks as the ship went down. Hundreds of people floundered in the stormy waters. Dozens died of exposure. Those who made it into lifeboats weren’t rescued for 24 harrowing hours. One boat was found nine days later.

Only 148 people survived. In all, 98 children perished, surpassing the 94 kids who were lost on the Lusitania and the 54 on the Titanic.

The consequences were swift and serious. The British people were furious, which effectively scuttled the relocation program. The sinking created a propaganda nightmare for Nazi Germany. Bleichrodt stood trial after the war on war crimes charges for the torpedoing. He was acquitted.

However, the most important reaction came in Hollywood, of all places, where outrage at the atrocity spurred a glamorous movie star into action.

MGM billed actress Hedy Lamarr as “the world’s most beautiful woman.” She was brilliant as well. Born into an Austrian Jewish family, she had immigrated to the United States to star on the silver screen in 1937. Tormented by the misery her kinsmen were enduring back on the Continent, the tragedy motivated her to join a secret high-tech operation.

She and a colleague clandestinely studied the sinking. They used their findings to develop the concept of frequency skipping so the U.S. Navy could construct jamming-resistant guided torpedoes. If successfully developed, it could give the Allies a high-tech advantage over their Axis enemies.

The Navy rejected the proposal as being too complex for the time. However, when Lamarr’s research was eventually declassified years later, it was fundamental in leading to the creation spread-spectrum technology. That’s behind today’s application of WiFi, which enables devices to access the internet.

And so ripples from that terrible September night still touch us nearly 85 years later.

Please follow DVJournal on social media: X@DVJournal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJournal