It’s a dog’s life at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue these days as presidential pooches Champ and Major settle into their new home. Major is the first shelter dog to ever live at the White House.

But just over a century ago, the Washington press corps was fascinated by a 1,500-pound member of the extended First Family who stole America’s heart.

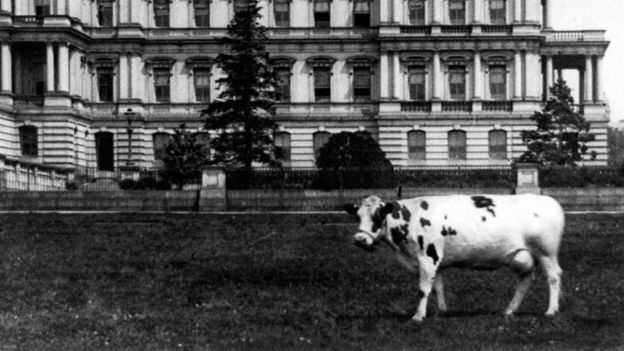

She was Pauline Wayne, a Holstein cow who captured the media’s fancy in a way no other presidential animal has before or since. Yet at the height of her fame, she came dangerously close to an unplanned trip to the slaughterhouse.

In the early 20th century, there was no dairy in the nation’s capital. Many Washingtonians kept a cow on their property (adding a hefty dose of methane to all the gas coming out of the Capitol).

The White House was no exception. Cows had been there ever since John Adams moved into the place in 1800. So, when William Howard Taft arrived in 1909 there was nothing unusual about his cow Mooly Wooly grazing on the South Lawn.

She was responsible for keeping the White House supplied with fresh milk and butter which, given the 300-pound Taft’s legendary appetite, was no small task.

But Mooly Wooly died suddenly in 1910, supposedly after eating too many oats. Her death was national news — The Washinton Post scolded, “She had never been instructed by experts that oats are for horses.”

Foreshadowing combative White House advisor Rahm Emanuel’s maxim, “Never let a crisis go to waste,” Wisconsin Senator Isaac Stephenson seized the moment of Wooly Mooly’s passing (Wisconsin is the Dairy State after all) and sent the Tafts a prize four-year-old Holstein.

Pauline Wayne

Pauline Wayne became an immediate media sensation. Her arrival at Washington’s Union Station was even covered by The New York Times.

It turned out Pauline was expecting. She soon gave birth to a bull named Big Bill in honor of the rotund Taft, which was sent to live on a Maryland farm.

It was all covered in breathless detail. Reporters dubbed Pauline “The Queen of the Capital Cows.” A 2015 profile of the famous bovine in The Atlantic said The Post in particular “…had something of an obsession with Pauline, covering her like US Weekly would cover a Kardashian.” That newspaper ran more than 20 stories mentioning Pauline between 1910 and 1912.

Pauline was more than the Tafts’ dairy source. She became their beloved family pet. So when the White House received an invitation that would allow her fans to see her in person, Taft happily obliged.

Pauline was the star attraction at the 1911 International Dairyman’s Exposition in Milwaukee. Little bottles of her famous milk sold as souvenirs for 50 cents. But she almost didn’t make it there.

To everyone’s horror, Pauline disappeared somewhere on the way. The White House issued a frantic APB for the bovine VIP.

It seems a railroad crew had mistakenly attached her special car to a group of regular cattle cars bound for the Chicago Stockyards. Pauline was spotted in the nick of time, sparing her — ribs and all (sorry, couldn’t help it) — from the butcher’s block.

After that close call, Taft declined all future invitations. But Pauline retained her rock star appeal. The Post bizarrely printed two different interviews with her. (Apparently, either she spoke English or the reporters were fluent in Cow Speak). A stage producer even asked if he could feature Pauline in his play. The offer made Taft laugh, but the answer was a firm “no.”

Taft wasn’t laughing when Woodrow Wilson defeated him for re-election in 1912. Despite the fame, life in the presidential fishbowl hadn’t been good for Pauline. She was in declining health, so the White House announced in February 1913 she was going back to where it all began. The Times reported, “President Taft believes that if she is taken back to Wisconsin and put on Senator Stephenson’s farm again, her youthful vigor will revive.” And eventually it did.

Pauline Wayne made one final claim to White House fame: She was the last cow to live on the premises. From the Wilsons on, the Executive Mansion’s milk came from a dairy, not a trip to the barn.

It seems strangely quaint now that a simple cow once commanded so much interest. And yet it was deeply humanizing, too. It reminded everyday Americans that their president got his milk the same way they did.

Maybe we should revive the custom of having our presidents grab a milk pail and head to the back yard first thing every morning. Heaven knows it couldn’t hurt.