It had been building for weeks. Americans could talk about little else, the tension and anxiety growing daily as the stakes climbed ever higher. The answer finally came on Nov. 8 and the country heaved a huge sigh of relief, glad that it was finally over.

One lucky person in California had won the record $1.9 billion jackpot.

As Powerball Fever simmers down, it’s an ideal moment to remember the time Americans were swept up in an earlier lottery frenzy. Unlike today’s drawings, that game wasn’t on the up and up. And it caused a scandal so immense it set back state lotteries for nearly a century.

This is the story of the scandalous Louisiana Lottery.

The Bayou State has many attractive qualities. But institutional integrity and virtue rarely rank among them. Moral ambiguity mingles with the magnolias making good people look the other way while creating a fertile climate for conmen.

Charles Turner Howard was one of them. A kind of business ne’er do well, he had a knack for drifting from one dead-end position to the next. After the Civil War, he began dabbling in the lottery industry and found his calling.

The Reconstruction Era was a time when money talked, and it practically screamed in Louisiana. Impoverished like most Deep South states, it was saddled with a Radical Republican government whose leaders were more concerned with lining their pockets than in promoting the general welfare.

After rounding up several partners, Turner turned up in Baton Rouge in 1868 and started spreading around money as generously as slopping whitewash on a barn wall. The state legislature soon gave him a charter allowing his Louisiana Lottery Company to operate for 25 years.

It was a sweetheart deal all the way. In exchange for being exempt from state taxes, all Turner had to do was make a $40,000-a-year contribution to a charity hospital. A staggering 50 percent of the profits went to Turner and his backers. Since there were no federal taxes on such business ventures at the time, Turner was poised to make a killing.

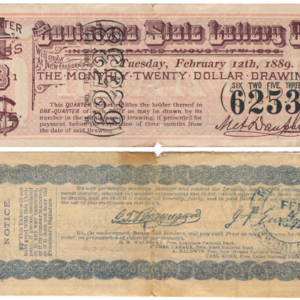

The Louisiana Lottery Company began operating in January 1869. It offered jaw-dropping cash prizes, including a $600,000 jackpot for its semi-annual big blowouts. Smaller prizes were available in daily and weekly drawings. Turner advertised them far and wide around the country with an emphasis on the South.

Money flowed in like the Mississippi River in flood stage. Very soon, the Louisiana Lottery Company was hauling in an incredible $30 million a year, making it the most lucrative enterprise in the state. Turner, an avid social climber, built one of the most beautiful homes in New Orleans’ Garden District and showered money on local charities.

However, he was not one to turn the other cheek. Not all of the Old South aristocracy took kindly to the nouveau riche interloper; many turned their back on him. Denied membership in the prestigious Metairie Jockey Club, Turner waited until the racetrack fell on hard times, then bought it and turned it into a cemetery.

He was remarkably adept at greasing the palms of everyone connected with keeping his operation going. Politicians, the press, and even the clergy were recipients of Howard’s generosity in one form or another.

Here’s how it worked: The Louisiana Lottery Company sold tickets. All ticket numbers were placed into a hopper where the winners were pulled out. To provide a veneer of credibility, two aging Confederate generals were each paid $10,000 every year (nearly $250,000 today) to witness the drawings.

But there was a dirty little secret the generals and the general public didn’t know. All unsold tickets were assigned to the company. And guess whose numbers turned up time after time? That’s right; the Louisiana Lottery Company won many of its own jackpots!

Howard was thrown from a carriage in an accident and died in 1885. He picked an opportune time to depart this world because public opinion was turning against him.

With a wave of morality rising, the Louisiana Lottery was the only such drawing left in the country by 1878, bringing it increased scrutiny. Reconstruction ended and many of the company’s former allies were replaced with Democrats who felt the lottery was ripping off poor working people. The walls were closing in.

When Louisiana adopted a new constitution in 1879, it included a clause extending the company’s monopoly to 1895.

That was the last straw. Allegations of bribery flew fast and wild. The state treasurer became implicated in the rapidly growing scandal and skipped off to Honduras with $1 million in state money to tide him over.

Democrat Francis Nicholls was elected governor in 1888 on an anti-lottery platform. Congress got involved in 1890 by passing a law banning the sale of lottery tickets in the mail and preventing lotteries from advertising in newspapers.

The jig was up. The legislature finally approved a measure banning the game in 1893. Bloodied but unbowed, the Louisiana Lottery Company limped off to Honduras and operated there for another two years.

But the damage was done. Most Americans had soured on lotteries. The bitter taste lingered in their mouths until the 1970s and 80s when cash-strapped state governments resurrected the practice to provide revenue.

Modern safeguards are in place today and folks watch lottery drawings live on TV as they happen, without any Confederate generals looking over their shoulders for good measure.