Susan Greenspon, then the editor of Main Line Sunday, was having lunch at her Ardmore kitchen table on April 4, 1991, when her phone rang. The sports editor called to ask if she heard the news that a plane had crashed at Merion Elementary School.

“I panicked. I had two little children at a Montessori school less than a mile away,” Greenspon recalled. She called a reporter and tracked down a photographer. (This was in the days before cell phones with cameras.)

Greenspon hurried to the school to direct coverage. Main Line Sunday was a part of the Main Line Times and the editor of the MLT happened to be on vacation just then. So Greenspon was in charge. In all her 35 years of news coverage, the retired editor said that day remains “seared in my brain” and stands out as an example of how journalists bear witness to history.

The horrific accident took the lives of seven people, including U.S. Sen. John Heinz III and those aboard the Piper Aerostar, the helicopter crew, and two first-grade girls who were on the playground when the fiery debris rained down from the sky.

“In the field in back of the school parts of the plane and helicopter were still smoldering” when Greenspon arrived. Bodies lay covered in sheets. Police, firefighters, and EMTs were on the scene as well as news crews from everywhere, she said.

Her heart went out to the parents who converged on the school to get their children. Greenspon spotted a woman still draped in a beauty shop smock running up to find her child. She pointed her out to the photographer, Anne Neborak, who got a shot of the tearful reunion, later winning first prize in a state journalism contest. In fact, all their coverage won awards, as did other media who reported on the horrific accident. But Neborak, who suffered from asthma, soon needed treatment herself from the fumes of the burning jet fuel and had to leave, Greenspon noted.

“It was chaos there,” she said. “You couldn’t get your head around it. There are no adequate words to describe the horror, to know these little girls lost their lives at lunchtime recess.”

Later, she learned the small plane carrying Heinz was headed to Philadelphia International Airport and having problems with its landing gear. The pilot radioed for help and a nearby Sun Company helicopter was enlisted to look and see if the gear had descended. The chopper flew beneath the plane and turbulence from its rotors caused the plane to dip; the two craft collided in midair bursting into flames before hurling to the ground in a fireball just outside the school. The helicopter’s blades landed in a driveway across the street. If it had been 15 minutes later some 400 children would have been on that playground for lunch recess.

“The day was filled with heroes,” said Greenspon. “So many people did so much.”

One of them was Tho Oldham, a mother who had lunch duty. A Vietnamese emigre, Oldham heard the roar of the low-flying helicopter and knew it did not sound right. She remembered helicopters dropping bombs from her childhood in Vietnam and immediately shepherded scores of children away from the playground seconds before the crash.

“I was looking up in the sky and saw the helicopter and the plane,” Oldham said in Main Line Sunday. “I had a really bad feeling something was going to happen. I blew my whistle and pushed the kids away from the school and toward the back fence. I told them to run as far as they could. I knew the helicopter was going to come down. The helicopter came down so fast, it came down like a rocket. I thought I was back in Vietnam.”

Custodian John Fowler and Ivy Weeks, a teacher, managed to grab seven-year-old David Rutenberg who ran to the school with his clothes on fire and put the flames out. Rutenberg suffered burns over 68 percent of his body.

The school building itself, made of Pennsylvania fieldstone as so many older Main Line buildings, did not catch fire. Firefighters from nearby companies quickly doused the debris, Greenspon remembers.

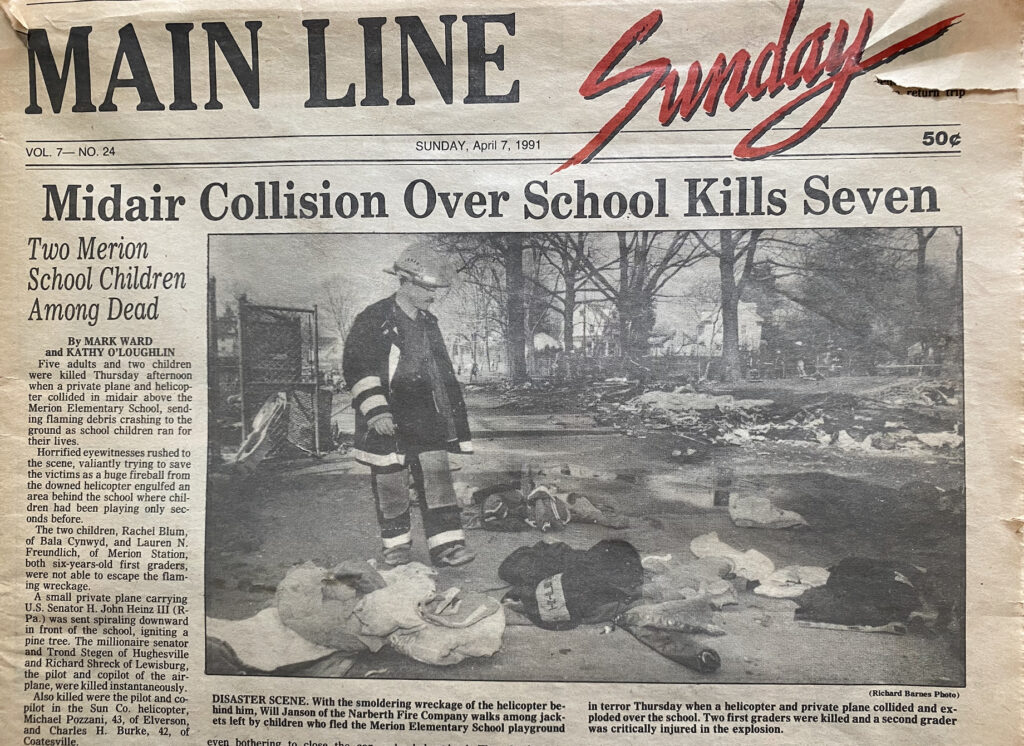

Later that day, she sent reporter Kathy O’Loughlin back with another photographer, Richard Barnes, and with the cooperation of local officials, they were able to capture stories and photos in the aftermath, walking the deserted hallways of the elementary school. A striking photo of a firefighter looking at the empty playground strewn with children’s backpacks and clothing resulted, which also won an award, she said.

Greenspon and her staff worked late into the night to get the paper done. Those were the days before much of the newspaper process was computerized, so photos had to be developed, contact sheets studied and pages laid out by hand.

“We were really small potatoes compared to the national news crews,” she said.

For a number of years, the Lower Merion School District held memorials at Merion Elementary. Trees were planted to honor the young girls who died, Lauren Freundlich and Rachel Blum.

However, this year, which marks the 30th anniversary of the disaster, no memorial was held because of COVID-19 concerns, a spokeswoman for the school district said.

But Greenspon is among those who can never forget that terrible collision. Now a resident of a Jersey shore town, Greenspon said the sound of helicopters still brings trepidation.

“Over the years, whenever I heard a helicopter over my house, I’d come out and look up and see what they’re doing,” Greenspon said. “I realize at any time it could crash down on a populated area. It’s unnerving. I don’t think most people think twice about it.”