(This article first appeared in Broad + Liberty.)

For the second December in a row, an official or employee associated with the Delaware County prison has publicly gone before county council to alert them to sinking morale and dangerous conditions within the prison.

The latest warning comes as the prison has witnessed ten deaths since the county’s own warden took over management of the George W. Hill Correctional Facility in 2022. Additionally, new data show the county is failing to lower recidivism rates — the singular measure by which the county said it should be judged regarding its management takeover.

(Note: While the official transfer of power from the private company to government management happened in April of 2022, the county’s new handpicked warden, Laura Williams, was installed in her position by February of that year, according to county documents.)

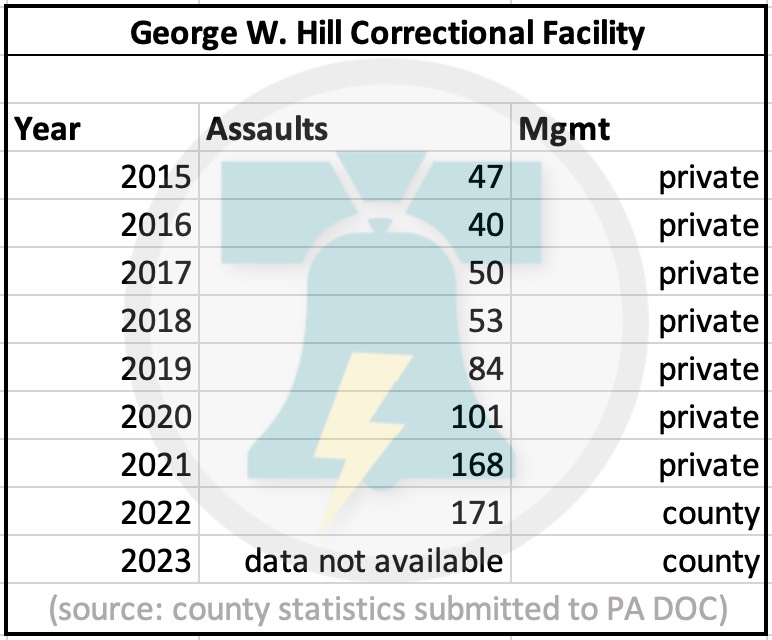

Other data like assaults and overtime pay also raise questions about whether overall conditions have continued to worsen since the county takeover as the prison’s union and some employees have claimed.

At the December meeting of council, Prison Employees Independent Union President Frank Kwaning implored the five members, all Democrats, to dig deeper into conditions at the prison.

“The [union] members are as frustrated as they could be. So through the members, I am told to let you know that the council should step in. Go to the facility. Talk to the members. The morale is at its lowest level. One may have thought that with this interim agreement that we have with the $3 raise that we have gotten — and we thank the council for agreeing with the union for the $3 raise — we were of the view that with the $3 raise, the morale was going to be up. But because of the treatment that has been meted out to the members, the morale is at its lowest, at best.”

Councilmember Richard Womack apologized.

“I’m sorry to hear that the morale is so low in the prison. I’m not sure why that is. It’s not our goal that the morale be down. And we would likely try and see if we could fix that in some kind of way.”

Councilmember Kevin Madden, who chairs the county’s Jail Oversight Board and who spearheaded the prison’s transition from private management to public, responded to Kwaning through the lens of the ongoing union negotiations.

“Mr. Kwaning, I recognize your position as head of the union. Given the fact there is an open negotiation over an agreement, I will, as always, refrain from engaging in a back-and-forth about such things. But I will certainly remind you and others that I am regularly at the facility and I am regularly interacting with the workforce. So, you know, any suggestion that council is not involved regularly with our facility would be inaccurate.”

In 2023, the prison saw five deaths, just as it had the previous year. One of those deaths was the “delayed homicide” of Mustaffa Jackson, which Broad + Liberty has reported on extensively. Of the four others, one was a suicide, one was a medical emergency for an inmate who was playing basketball, and two appeared to be overdose deaths at the prison’s intake department, meaning the persons may have taken the fatal dose sometime before entering the facility.

According to statistics dating back to 2015, there is no consecutive two-year period under the previous private management for which there were ten deaths. The highest two-year death total under the private management was seven, across the years 2018-19.

Minutes from the November meeting of the Jail Oversight Board also indicate that the county has made no progress in reducing recidivism, its key motivation for moving management from privately run to government.

Prior to the government’s management takeover, county spokeswoman Adrienne Marofsky said of the county’s ambitions, “There really is just one metric [to be judged by]: recidivism. Currently over 6 out of 10 inmates at GWH have been there before. We can do better. And doing better would mean a reduction in the prison population, and a reduction in the cost to the taxpayer.”

More than 21 months into the project, none of those goals are near fruition with the exception of reducing the overall population.

Minutes of the Jail Oversight Board from the last three years of private management, 2019 through 2021, show the GWHCF’s recidivism rate hovered at 60 percent — exactly as Marofsky had described.

But the recidivism rate in 2022, in which the county took over in April, held at 61 percent.

Meeting minutes from November 2023, show a slight upward tick to 63.8 percent.

Additionally, there has been no reduction in cost to the taxpayer so far.

When a consultant group in April 2021 presented several budget scenarios to the Jail Oversight Board as it prepared to transition, it predicted the county’s topmost yearly cost would be about $49 million. But that scenario included a mostly full prison.

The lowest cost scenario was $43 million, a cost which assumed a far lower average daily population.

However, even though county officials have reduced the prison population by 20 percent, the 2024 budget for the prison is $53 million. Shortly after the November elections, the county council raised taxes, with escalating prison costs contributing to that decision.

Assaults held steady in the first year of government management according to the annual prison data it submits to the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections. However, the 2022 assault numbers came amidst a drastically lower population.

Finally, overtime data from the county shows a steep increase across the past year.

By November of 2022, the county had spent roughly $3.9 million on overtime. By November 2023, that figure climbed to $6.4 million.

The numbers could be indicative of a workforce that is stretched thin and experiencing difficulties retaining staff.

Although Kwaning is the union president for the correctional workers, he is no longer employed at the prison. The new county management terminated his employment along with the union vice president, Ashley Gwaku, during the transition.

Kwaning, Gwaku, and the rest of the union allege the county’s decision to fire the top two leaders of the union was a strategic move to weaken the union. Warden Laura Williams said the pair were let go because of suspensions they had been given previously under private management.

According to an October report from the Inquirer, “Kwaning estimated that about 40 to 50 union employees were terminated by the county during the management transition before officials instituted an arbitration process that includes a member of the human resources department acting as a mediator.”

In December 2022, guards delivered a similar message of low morale and dangerous conditions to the council.

“We are … in fear of our safety on this job,” Albert Johnson, a security guard, said at the time. “As of yesterday — two inmates stabbed. There have been more deaths in this prison since the county has come on. We are fearful for our lives with cells that do not lock, from inmates that come out when they want. We get feces, we get urine thrown on us on a daily basis.”

The county did not respond to a request for comment by deadline.