(This article first appeared in Broad + Liberty)

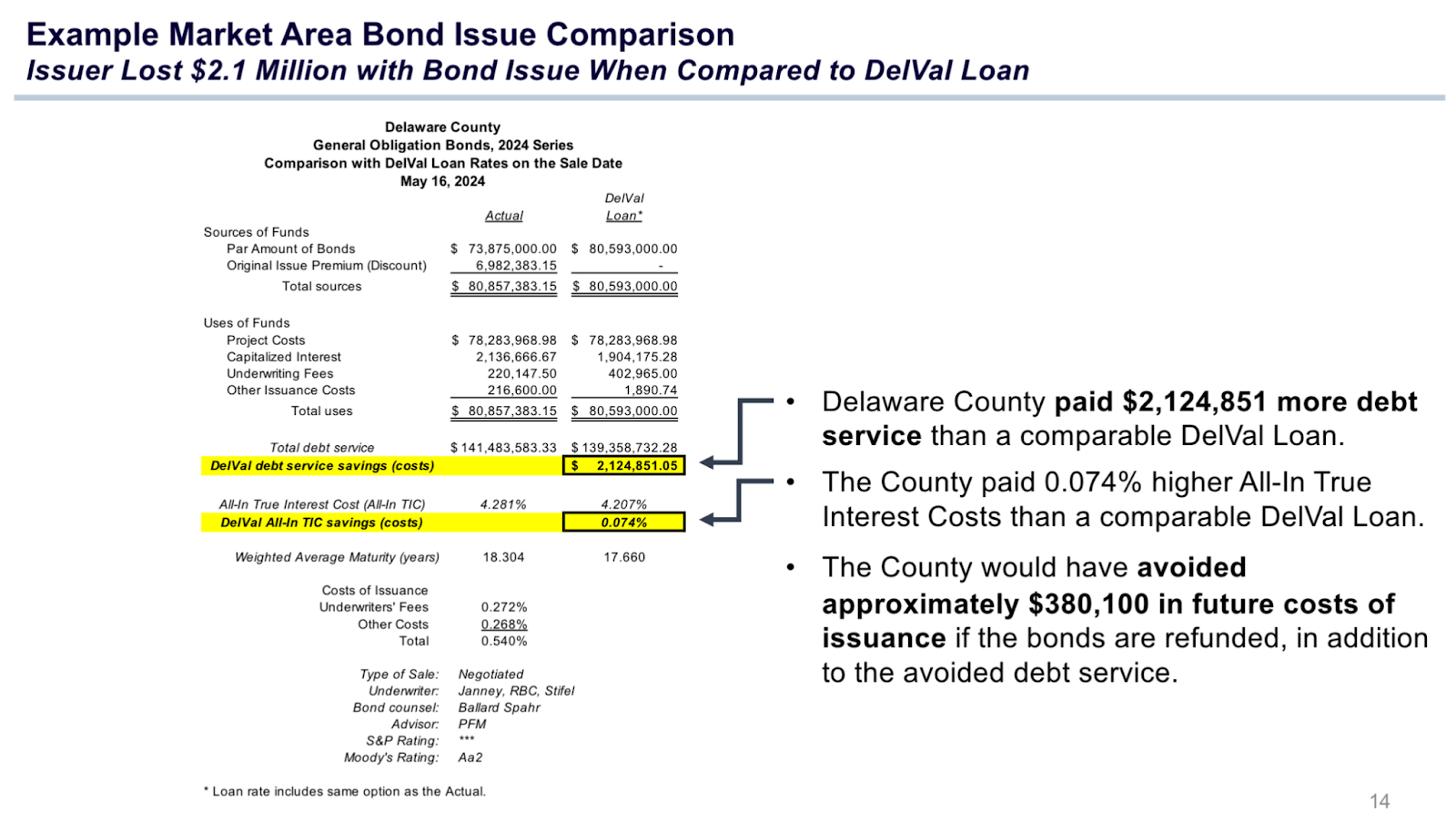

Delaware County could have saved $2.1 million dollars when it issued bonds this summer but chose not to, preferring instead to go with private entities as opposed to a regional government-associated entity set up for the sole purpose of saving governments money on loans.

That’s according to a loan analysis document from the June meeting of the Delaware Valley Regional Finance Authority, or DVRFA.

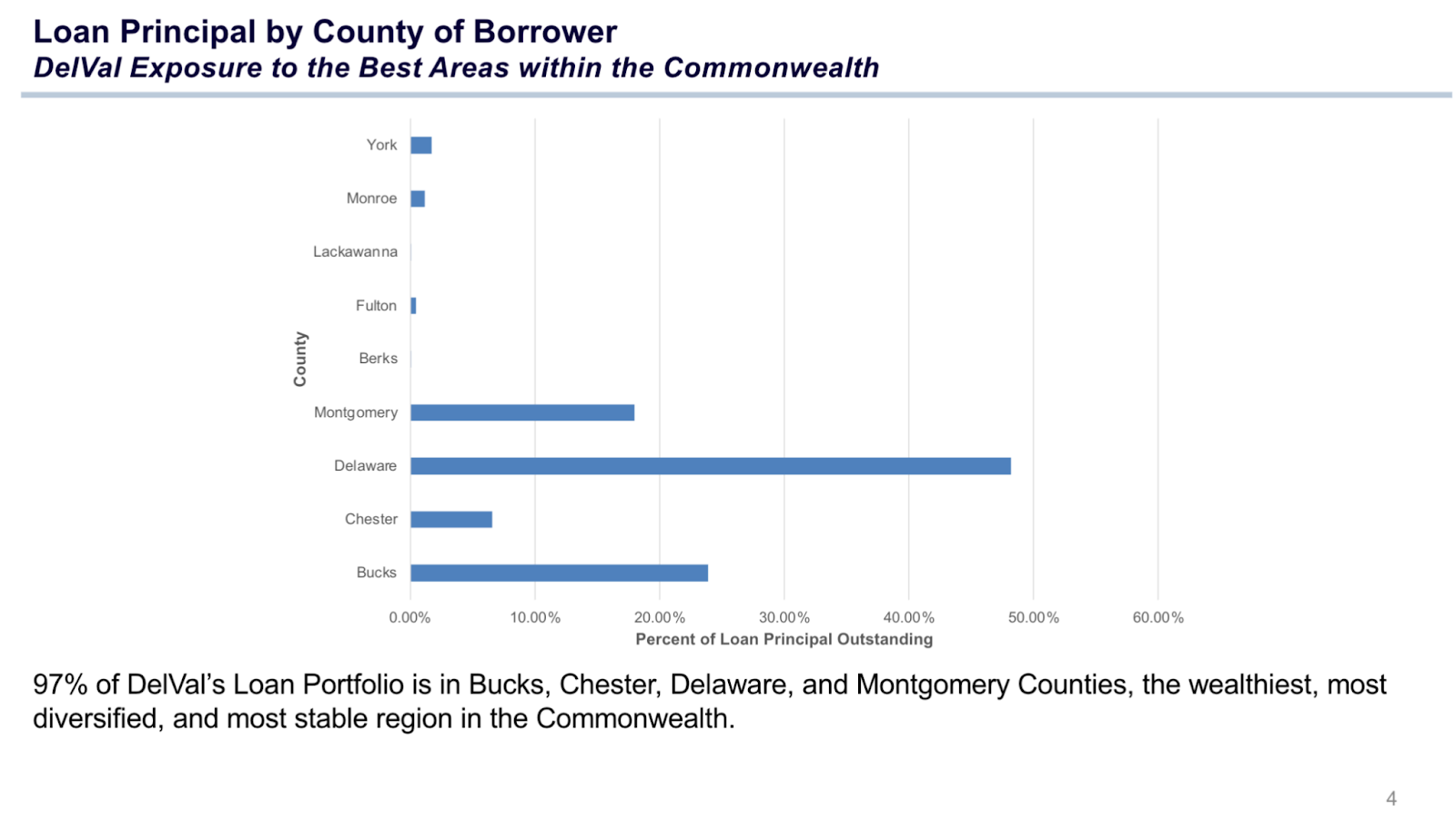

The DVRFA was created by Philadelphia’s four suburban counties in 1985 with the specific aim of providing low-cost loans, like bond issuances, for any kind of government in that geographic area, whether it be school district, municipality, or county. In essence, the DVRFA decided to pool money from the counties and lend from it to local governments directly, issuing its own debt to save costs.

When Delaware County decided this year to issue bonds through private lenders, it could have borrowed from the DVRFA but decided to take a more costly route, the DVRFA analysis concludes. After accounting for all items associated with the bond offering like capitalized interest, underwriting fees, and “other issuance costs,” Delaware County “paid $2,124,851 more debt service than a comparable [DVRFA] Loan,” the analysis concludes.

The otherwise sleepy and staid world of bond issuances takes a totally new life at present, as Delaware County has recently acknowledged it is struggling with a significant structural deficit, has an alarmingly low “rainy day fund,” and as a consequence is likely to approve a 23.8 percent tax increase on citizens for 2025.

The county is standing by its decision, but did not necessarily dispute the DVRFA’s analysis either.

“We are committed to being responsible stewards of taxpayer dollars, and financial markets are extremely complicated,” a county spokesperson told Broad + Liberty. “We consulted with leading experts in public finance and municipal bonds and determined, with their advice, that seeking funding on the open market was the most prudent course of action.”

The county has shown, however, an affinity for the DVRFA. According to the same June document, Delaware County is the government with the largest amount of outstanding loans with the DVRFA.

Delaware County’s representative on the DVRFA board is David Landau, who, as secretary, signed the minutes of the June document at issue in this report. Broad + Liberty also reached out to Landau to see if he could give deeper insight into the choice, but that request for comment was not returned.

The analysis also notes that law firm Ballard Spahr acted as the “bond counsel.”

Ballard Spahr has political ties to the current council. According to Councilwoman Christine Reuther’s LinkedIn resume, she worked for the firm for about five years ending in 1993. In a more recent show of those close connections, however, Ballard held a fundraiser for Reuther in 2019, according to a page from Reuther’s campaign website. Although the advertisement for the fundraiser on the website has since been taken down, it was saved through the Internet Archive, a nonprofit that archives billions of webpages daily to create a historical archive.

The firm’s political committee gave $2,000 to Council Chair Monica Taylor’s re-election in 2023.

As Broad + Liberty reported in July, the county’s spending on outside, third-party counsel has skyrocketed since Democrats took control of the council after the 2019 elections. In that last year of Republican control, spending on third-party attorneys or law firms was about $400,000. In 2023, that figure had ballooned to $4.5 million — the highest spending of any of the collar counties.

Ballard Spahr has been the biggest recipient of that new spending. In 2023, it billed the county $582,780.

The county did not provide a response for a question seeking the amount of Ballard’s fees for its work as bond counsel.

When Broad + Liberty does an analysis of third-party attorney spending, it begins by filing a Right to Know Law request seeking documents showing any spending that fits that description. It’s not clear, however, if fees from acting as bond counsel would be included in those kinds of documents because the payment is folded into the overall cost of the bonds, much like a real estate agent or title company is paid out of closing costs and not from the buyer’s personal checking account.

While there’s no explicit evidence of any kind of quid pro quo between Ballard Spahr and the council, Democrats previously assailed Republicans for exactly these kinds of relationships.

“I’ve come to conclude a big part of the problem is that Delco citizens pay a corruption tax,” said Democratic former councilman Brian Zidek, in 2019. He pointed out what he thought was “instance after instance of no-bid contracts being granted to Republican Party insiders.”

In 2019, the Philadelphia Tribune reported on the Democrats running for council pledging to restore transparency, “with Schaeffer and fellow Democratic candidates Monica Taylor and Christine Reuther calling for an end to ‘sweetheart deals’ and patronage.”

“[Delaware County] was always a place where you had to know a guy to get something done,” Reuther said at the time. “We’re running to change that.”

Council is expected to vote Wednesday night on the proposed 2025 budget which includes the 23 percent tax increase. Enough council members have already signaled their intention to vote for the budget to reasonably expect that it will pass.

(Editor’s Note: Delaware County Council did pass the 2025 budget Wednesday evening, raising taxes 23 percent.)