(This article first appeared in Broad + Liberty)

For two hours, the residents vented their anger.

“I know we’ve got a tremendous increase that’s being proposed to our taxes. I know what it’s like to struggle to make ends meet and the county, the state, the federal government — everybody has to deal with that. The problem here is the county can at the stroke of a pen, just get more money. You can impose that on every citizen that’s here. Myself and every citizen that’s here can’t do that. We have to seek other means. In other words, we’ve got to tighten our belt and we’ve got to cut the fat.”

Pat Carnevale wasn’t alone. He was one of dozens of voices expressing dismay and frustration last December as Chester County was on the cusp of approving a thirteen percent real estate tax increase — three times larger than the previous four percent tax increase in 2020.

If Chester County had any grace, anything that shielded it from more wrath, perhaps it was only that weeks before, neighboring Delaware County had dropped a whopping 24 percent tax on its citizens. As bad as a thirteen percent tax increase would be, at least it wasn’t Delaware County.

Chester County’s three-person board of commissioners empathized with the frustrated crowd. But when the rhetoric, empathy, and public comment was over, the two Democrats voted ‘yes’ on the tax increase, and the lone Republican voted ‘no.’

Just before casting his ‘yes’ vote, Chairman Josh Maxwell (D) said inflation and other minor issues had nibbled at the edges of the budget, but citizens could rest assured knowing most of the thirteen percent increase was really due to two “big ticket” items: a county-wide refresh of the radios used by every law enforcement agency in the 759-square mile county, and a series of upgrades to the county prison.

The county last updated the radios in 2015, and with a ten-year lifespan, it was time to reinvest.

As for the prison, was there anyone in the county who had forgotten the saga of Danelo Cavalcante, a Brazilian national who escaped from the county prison in the fall of 2023, and remained on the loose for two weeks?

“I don’t want anyone here to think that this county is interested in expanding government tremendously or increasing annual spending in perpetuity,” Maxwell reassured the crowd that had just vented its anger at him. “Those are the two big ticket items that in addition to a little bit of inflation we absorbed this year.”

Despite Maxwell’s reasoning, a Broad + Liberty analysis of the last ten years of budgets for the county seriously undermines that rationale. The county disputes many parts of the analysis, which will be generously incorporated into the story.

The analysis shows for the millions of dollars devoted to prison upgrades, much of that up-front capital was provided by a bond sale — in other words, the county took on debt, and would be paying it off over the course of several years.

As for the radios, a sizable chunk of the money set aside for that category of spending in the budget was coming from federal and state grants.

The county’s prison spending is spread out over ten years which should have spared citizens from the need for a massive, one-year tax hike. And the county’s new law enforcement radios could have been financed to lessen the pain, but officials didn’t examine the possibility.

The Broad + Liberty analysis that follows below asserts the county’s tax increase was needed to cover years of growth in spending across numerous areas of county government, much of which was driven by salary increases and spending growth in the “human services” category.

Prison upgrades

At the December meeting, Commissioner Maxwell listed multiple improvements to the county prison, “about $6 million going towards security upgrades to that prison that hasn’t been touched in decades,” he told the angry crowd.

Those improvements included new security features like specialized fencing, and adding a K-9 unit. Furthermore, the county was investing in the core building by replacing the roof and upgrading features like the air conditioners and air handlers that provide fresh air to the interior. Increasing staff salaries was also a priority.

Before diving further into the prison spending, it’s important to understand a couple of features of large government budgets and how some of those features work in Chester County.

Large purchases or investments are generally called “capital expenditures” or “capital spending.” A good definition can be found at business-standard.com, which says, “Capital expenditure is the money spent by the government on the development of machinery, equipment, building, health facilities, education, etc. It also includes the expenditure incurred on acquiring fixed assets like land and investment by the government that gives profits” or dividends in the future.

Chester County splits its capital spending into two different funds: the Capital Improvement Fund which pays for capital expenditures by borrowing money by selling bonds, and the Capital Reserve Fund, which pays for large investments with cash.

The prison upgrades were largely placed under the Capital Improvement Fund, which, as just explained, means those purchases were financed with debt.

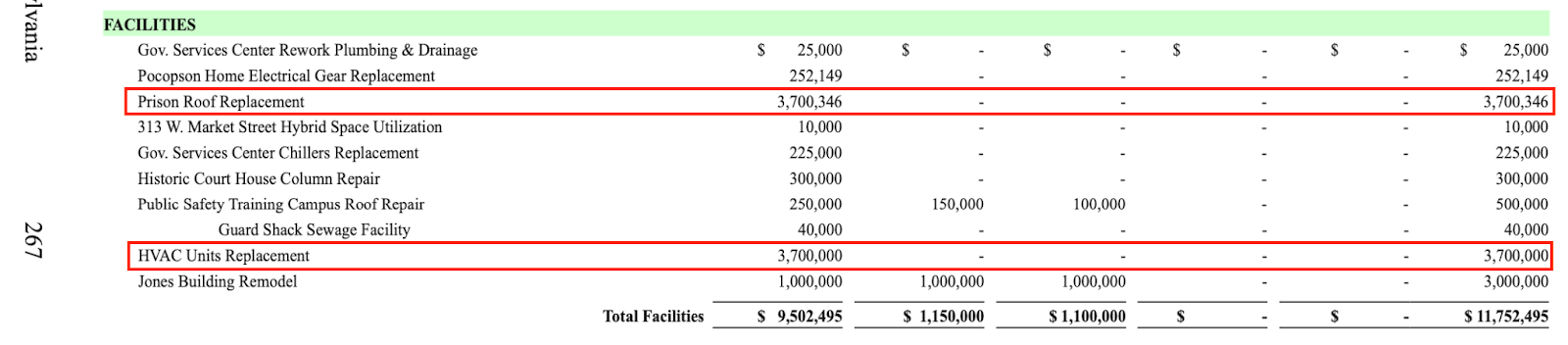

Page 267 of the 2025 final budget document provides a breakout of the Capital Improvement Fund, and shows $3.7 million for the prison roof replacement, and another $3.7 million for heating and air replacements. Together, the two projects total $7.4 million.

According to all of the budgets from 2016 to present, the county’s outlays for its borrowing — usually called “debt service” — was not set to be significantly greater in 2025 than in any of the previous four years. Taking all that context together, it’s correct to say the prison upgrades were expensive, but that the cost is to be spread over many years.

(Source: Chester County budget documents, 2016-2025)

With this in mind, Broad + Liberty asked why a steep increase in taxes was necessary if outlays for debt service for the prison upgrades weren’t significantly increased as well.

“The County drew down the Debt Service fund balance in 2024. The 2025 budget necessitated an increase in debt service millage to cover the budgeted [debt service] expenditures totaling $55.9 million in 2025,” said, Julie Bookheimer, the county’s chief financial officer.

The first part of the answer is incomplete without the context of how much the Debt Service fund balance should be, and where it stood at the beginning of the fiscal year. The second part of the answer merely repeats the question in the form of a statement.

When the county was asked this question again in a different way, the county replied: “While prison facility improvements are in the Capital Improvement Fund, there are more than $3 million in increased prison-related costs within the 2025 operating budget.”

In this response, the county acknowledges that most of the prison one-time improvements will be financed with bonds, and as such, the impact is spread out over many years, but that the prison line-item in the operating budget has gone up by $3 million, meaning that is new spending that will likely be recurring every year.

The county further itemized the $3 million by saying “$2.35 million [is] for medical treatment, and other items such as food and clothing supplies, repair and maintenance, training and staff development, utilities, and vehicles and general expenditures related to the addition of K9s.”

Still, that is only $3 million in “new” spending in the operating budget. The thirteen percent tax increase is set to raise an additional $26.8 million. There’s a long way to go.

Law Enforcement Radios

At the December meeting, Maxwell gave an explanation of payment for new law enforcement radios that would appeal to the fiscally conservative.

“These police radios last ten years, so we’re moving them from one side of the budget to another,” he began.

“Previously the county would take on debt for twenty years to pay for those types of work, but the radios only last ten years. So, next year you’re going to be paying for two radios for your tax bill, one that’s no longer working and one we just bought for our police officers. In eleven years, because we moved it over and now we’re paying it as you go and not taking on bonds for it — eleven years from now, we’ll only be paying for one radio. So we have to make a sacrifice today, but it’s not a choice that this board made ten years ago. But eleven years from now, we won’t be paying for things that we aren’t using anymore,” Maxwell concluded, subtly portraying his Republican predecessors as less responsible.

The undisputed cost of the radio purchase is $12 million dollars. One item left unmentioned by Maxwell, however, was that the county was splitting the purchase across a two-year period, about $6 million in 2025 and another $6 million the following year.

The purchases are listed in the budget’s “Capital Reserve Fund” which, as explained before, is a fund for capital expenditures that are not financed but are on a pay-as-you-go basis, like Maxwell said.

Maxwell’s speech about the radios could be seen as offering a false choice to residents, however. In it, he talks about financing the purchases for 20-year periods. Financing instruments, like bonds, can be issued for a variety of time periods.

Broad + Liberty directly asked why the county did not take on ten-year debt for a ten-year capital investment, or, why the county didn’t take out 20-year bonds and pay them off ahead of schedule. Either option would satisfy Maxwell’s desire to “only be paying for one radio” eleven years from now.

“At that time, the interest rates were higher than in previous years. Therefore, the cost to borrow was (and is) higher. Debt incurred over twenty years should be for assets that have an expected life of twenty or more years. This equipment has an estimated useful life of ten years or less. The County continues to manage debt in a responsible manner as attested to the Triple-A rating by all three rating agencies,” Brookheimer said.

When asked, the county said it did not do any analysis at all on financing the radios, regardless of whether over a ten-year period or otherwise. The county further said it did not shop for loan pricing from the Delaware Valley Regional Finance Authority. The authority is an agency in southeast Pennsylvania created by Philadelphia’s four collar counties to tackle problems just like this. The counties pool their money together into the DVRFA which then gives bond loans at an interest rate lower than the retail market. In essence, the four counties created their own credit union.

Finally, the Capital Reserve Fund — the capital expenditure account that does not borrow but makes investments on a pay-as-you-go basis — is substantially funded from outside sources in the 2025 budget. The county agreed that “the radios are 43.7 paid for by federal and state grants.” This, too, would seem to mitigate the impact to the taxpayer. When Maxwell and the county talk about the radios, they give the full price tag of $12 million to justify the price increase, but seldom mention that grants will pay a considerable portion.

General Growth

Setting aside the issues of the prison and radio improvements, the county has seen growth in the last five years, in population, the tax base, and in the overall size of the county government.

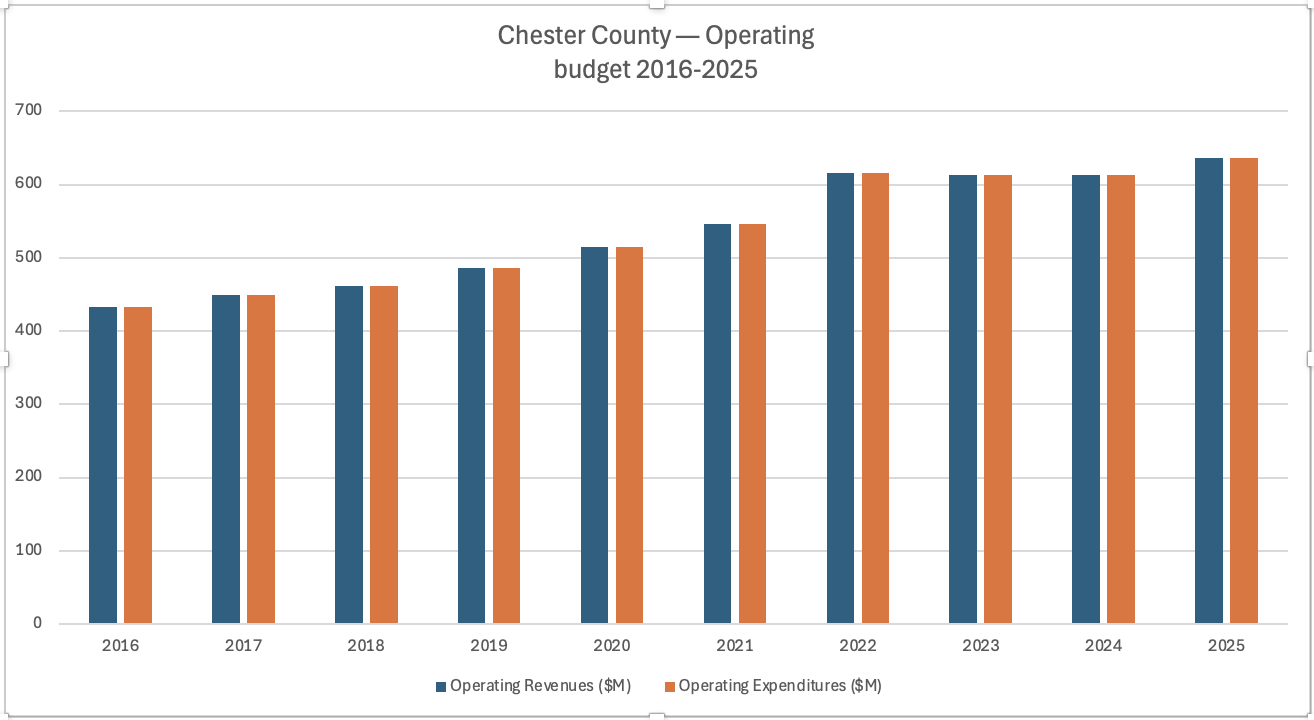

It is important to understand this next part of the analysis focuses exclusively on what’s called the “Operating Budget.” This is the part of the budget over which the commissioners have the most control on an annual or even day-to-day basis. This analysis excludes the “consolidated budget” which contains many items that are done in partnership with the state or federal governments, and which also remain mostly static in cost from year to year.

According to data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Chester County’s population grew from about 534,000 to 561,000 from 2020 to 2024 — a five percent increase.

The county budget has grown at least five times faster than the county’s population since Democrats took the majority on the county board of commissioners in 2020.

The county’s revenue from real estate taxes has grown from $169 million in 2020 to $212 million in the 2025 budget — a 25 percent increase. Not all of that is from tax increases. Some of that comes from new ratable: new residential or commercial developments whose taxes are incremental to the existing property tax base.

However, the Broad + Liberty analysis demonstrates that the incremental spending — and therefore growth in county government — does not stop at 25 percent. In addition to spending $43 million in additional real estate tax receipts, the 2025 budget uses $17 million in funding from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, or ARPA.

Furthermore, the 2025 budget spends $10 million from “appropriated fund balances.” In layman’s speak, this is cash already on hand in reserve funds. It is not regularly recurring revenue, like real estate taxes that are guaranteed to come in every year. Like any savings account, it is drawn down when money is needed to cover operating expenses.

Adding all these pieces together, in order to balance the 2025 budget, the county spent $43M in additional real estate tax revenue, generated primarily from a doubt digit tax increase, $17M in federal covid relief funds, and $10M in reserves, for a total increase in $70M.

By incorporating the ARPA and fund balances, the Broad + Liberty analysis concludes the county’s overall spending has gone from $169 million to $239 million — a 41 percent increase. To put in the plainest terms, since Democrats took a majority in Chester County, county government has grown 41 percent according to our analysis.

The county disputes this analysis, especially the idea that one-time funds are going to recurring expenses.

“Taxes were raised to cover ever-increasing expenditures as well as the large ticket items discussed. Revenues have not been growing at the same rate as expenditures over the last five years despite the County’s efforts to control costs,” Brookheimer said. “Those one-time funds were used primarily for one-time expenditures as explained in previous email responses. In other words, [the] vast majority of those expenditures will end as the one-time funds end.”

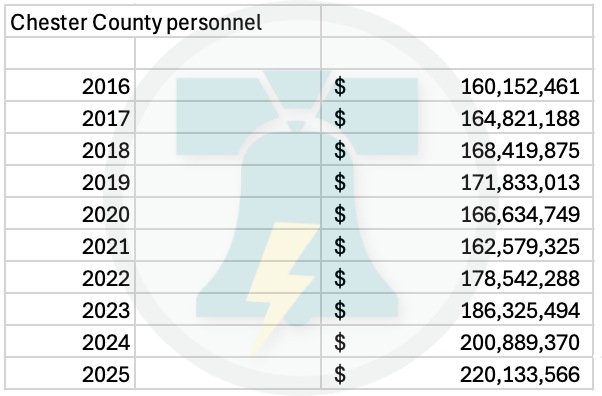

What’s indisputable is that many areas of recurring spending in the county budget have seen continual increases in the last five years. Personnel costs for the county have exploded since 2020.

The county noted that in 2023, it took over Community Transit, which added to the overall personnel costs. It should also be noted that Community Transit also came fully funded, so the county did not have to create additional revenue to pay for those employees.

However, an analysis of the county’s 2024 payroll obtained previously by a Right to Know Law request shows that Community Transit accounted for $3.9 million of payroll in 2024. Even when adjusting 2024 and 2025 payroll to exclude Community Transit, payroll is still up by roughly 21 percent when compared to 2022.

The county defended the increase in personnel spending.

“In 2022, many salaries were adjusted as a result of a salary study. The purpose of the salary study was to ensure that Chester County remains competitive with the surrounding counties so that we can maintain our workforce. Also, the cost of benefits increased by [fifteen percent] due to market demand – coming off COVID.”

The county gave two direct examples. “Correctional Officer – Base salary in 2021 – $41,939; Base salary in 2024 – $55,399. Regional Park Ranger – Base salary in 2021 – $39,472; Base salary in 2024 – $46,754,” Brookheimer said.

More changes in personnel spending may be in the offing.

“The County is currently performing a salary study with the plan to potentially implement in 2026. The County wants to continue to attract talented / qualified employees and remain somewhat competitive with surrounding counties and the private sector to continue the services expected to be provided by the County. At this time, the cost is not known since the study is not complete. However, it is not anticipated that the cost will be on the same level as the 2022 study since a study had not been done for twenty years prior to 2022,” Brookheimer said.

The Human Services category has also seen tremendous growth under the Democrats’ watch. The category’s 2020 budget was $234.3 million. By 2025, that figure had ballooned to $312.3 million — an increase of $78 million dollars, or 33 percent. (Some of that category growth could be from salary increases, and as such, could overlap with previous references to growth in personnel costs.)

SUMMARY

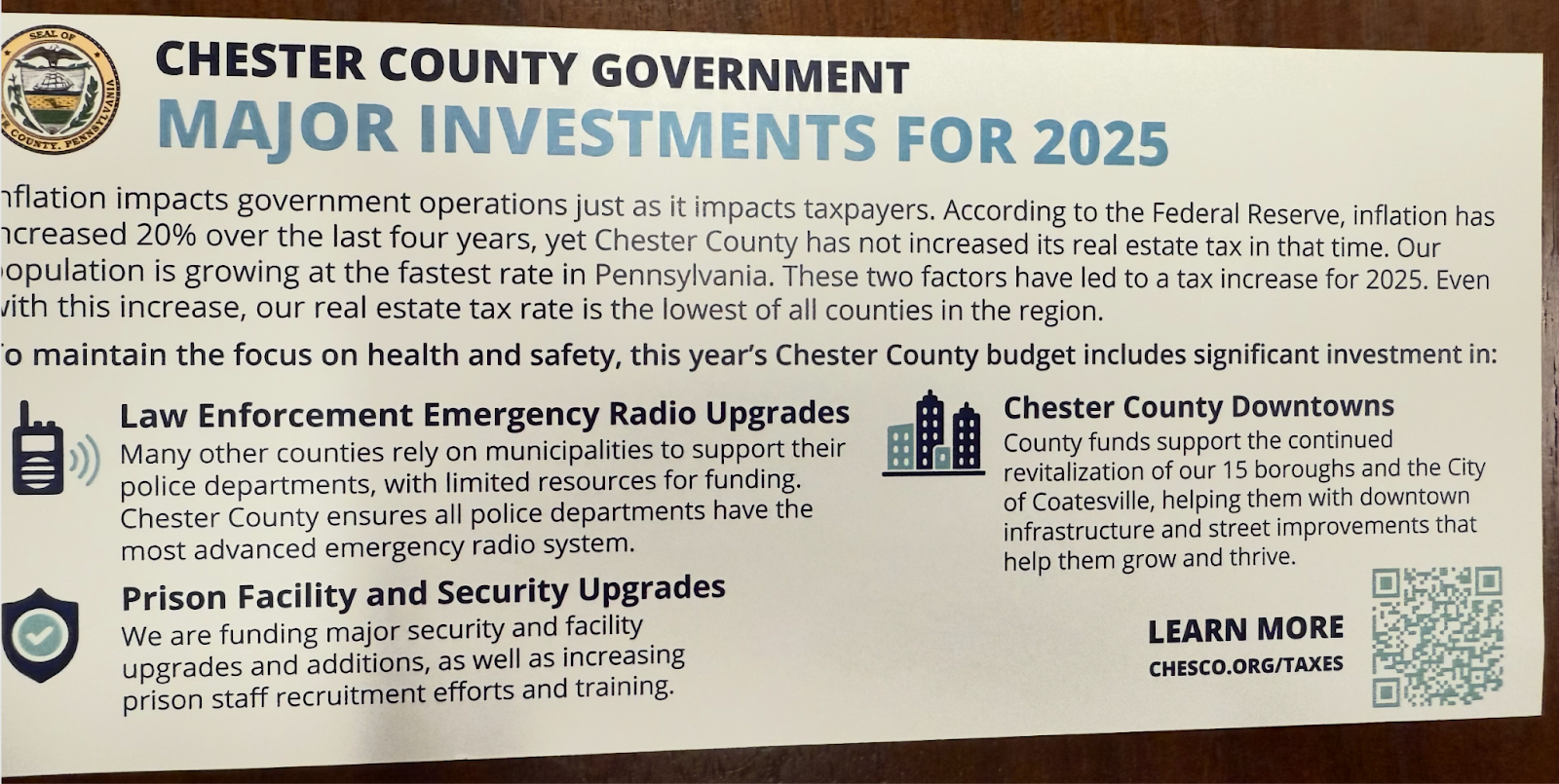

Like many other counties or municipal governments, Chester County also says inflation forced many of its budget increases. In an online “information sheet” the county pointed us to explaining the tax hike, the flyer led with the fact that the county was absorbing higher prices. Only after that did it tout the prison upgrades and radio refresh. The county sent similar mailers sent to citizens.

One significant element of the “big ticket” spending remains elusive: What will happen to that new revenue once the “big ticket” items are paid for? If the county raised taxes to pay $12 million in cash for new radios ($6 million in 2025, and $6 million in 2026), then what will the county do with that cash flow once the radios are paid off?

“At this point, we have not started fine tuning the 2026 and 2027 budgets to adequately determine our funding needs. However, with a County of our size, there are always projects surfacing that need immediate attention. One big ticket item paid for in the near future does not necessarily mean there are excess funds available in future years as other projects or needs surface. Inflation and rising costs continue to impact the County service and operational costs.”

If both “big ticket” items were paid for in up-front cash in the 2025 budget, they still wouldn’t add up to the total tax increase. The two “big ticket” items together totaled $18-19 million. The county’s tax increase is scheduled to bring in $26.8 million — a difference of about $8 million.

At a minimum, the county’s communications about the impact of the “big ticket” items — especially the first-year impact and how that would affect taxes and why that necessitated an immediate tax increase — seems to have been incomplete.

The county could have spread out the costs of the radios with debt that was scheduled to last the lifetime of the equipment — ten years — but did not choose even to shop those options. Additionally, state and federal grants are funding a sizable portion of the overall purchase, at least in the first year — a fact rarely, if ever, mentioned by Maxwell or other county officials.

Most of the costs of the prison upgrades are financed, which should lessen the need for an immediate infusion of new cash, but the county has rarely spoken about those projects as payments spread out over time.

The county’s overall growth, meanwhile, is undeniable. As explained above, Broad + Liberty’s assessment is that since 2020, county revenues have grown 41 percent. Although the county disputes our analysis, it concedes that the operating budget is up 29 percent over that same time — an incredible amount of growth that can’t be explained away by just inflation or incremental growth forced on the government by the Covid-19 crisis. A county budget that goes up 29 percent in five years would seem to directly contradict Maxwell’s assertion that the county wasn’t “expanding government tremendously or increasing annual spending in perpetuity.”

(For the sake of story length, Broad + Liberty obviously could not incorporate every response or answer to a question to which the county responded. In an effort to provide the county with as much voice as possible to its answers and comments, Broad + Liberty is publishing both sets of those email conversations available here: SET 1, SET 2. The questions are posed by Todd Shepherd; Chester County CFO Julie B. Bookheimer provided the answers. The 2019-2025 budgets are all available at this county website. Years prior to 2019 can be accessed here.)