If you are of a certain age, you’ll remember when you couldn’t turn on your TV without being bombarded by helpful advice during commercials. Mr. Whipple warned against squeezing the Charmin, Miss Chiquita hustled bananas with a merengue flair Carmen Miranda would have envied, and Mrs. Olson saved more troubled marriages than Dr. Phil simply by telling housewives to switch coffee brands.

Folks like Geraldine the Plumber, the Tidy Bowl Man, and the poor, woebegone Maytag Repairman. People we knew and trusted, like close family friends.

Except, they weren’t friends. They weren’t even real. They were fictional characters created specifically to make us buy their products. And they were good at it, too. So much so that the 1960s and 70s were a Golden Age for commercials featuring made-up pitchmen and women.

They owed their success to a forgotten forebearer. To understand why she was so successful, you must first understand the problem this advertising pioneer addressed.

In 1900, when you needed to get somewhere, you took a train. It was both affordable and the fastest way to get there.

But riding the rails had a huge headache. The steam engines that powered passenger trains burned tons of coal. Their smokestacks spewed a steady stream of thick, black clouds every mile of the way. Much of it was sucked inside the cars. When passengers arrived at their destination, they were often covered in dark soot. It was even worse in summer when the only relief from stifling heat was open windows, making a bad situation even worse.

Then, the folks at the Lackawanna Railroad had an idea. (Though it was officially the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad, it went by its middle name.)

Without delving into too much science, the soot problem was at its worst when engines burned bituminous coal. Tar-like bitumen is similar to asphalt, and boy, does it put out clouds of smoke when burned.

So, the Lackawanna switched to cleaner-burning anthracite coal. Although that didn’t eliminate the soot problem completely, it significantly reduced it.

Now, railroad executives faced a new challenge: how to let the rail-riding public know about the improvement. And the genius of Earnest Elmo Calkins came to their rescue.

Called the “Dean of Advertising Men” and “arguably the single most important figure” in his profession in the early 20th century, he dreamed up fictional commercial characters. Left deaf by a childhood case of measles, he became the editor of his college newspaper. (And he only graduated by the skin of his teeth; when professors wanted to expel him for failing geology, school trustees stepped in and made sure he got his sheepskin.)

In the early 1890s, he entered an ad contest to promote Bissell carpet cleaners as Christmas gifts. His entry was selected from 1,433 entries, earning him the $50 prize (about $2,000 today) and launching him on a new career path.

He and a partner started their own business in 1902, and the advertising industry was forever changed. That was when the Lackawanna turned to him for help.

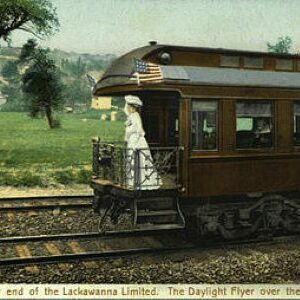

Calkins’ answer was the creation of Phoebe Snow. She was an attractive young socialite who (for some never-explained reason) always traveled between the Big Apple and Buffalo, N.Y., and always on the Lackawanna RR. And she always wore glistening white dresses and hats, too, emphasizing how the cleaner-burning coal kept passengers’ clothes clean. The point was driven home in short poems (in the rhyming meter used in the nursery rhyme, “The House That Jack Built”).

“Says Pheobe Snow

about to go

upon a trip to Buffalo,

‘My gown stays white

from noon till night

upon the Road of Anthracite.’”

(The Road of Anthracite was the Lackawanna’s slogan.)

Phoebe was an instant hit and soon was recognized around the country. Model Marion Gorsuch was frequently photographed portraying the character.

For nearly 20 years, Phoebe was the social arbiter of rail travel. Until World War I ended her career when Uncle Sam banned using the superior coal for passenger trains. Pheobe said so long in a farewell ad.

“Miss Pheobe’s trip

without a slip

is almost o’er.

Her trunk and grip,

Are right and tight

without a slight.

Goodbye, old Road of Anthracite!”

But Americans hadn’t heard the last of her.

In 1949, the Lackawanna launched a streamlined passenger train named the “Phoebe Snow.” It ran the almost-400 mail trip from Hoben, N.J., to (where else?) Buffalo in eight hours until service ended in 1966.

Yet even then, the name refused to die. If it sounds familiar to you, here’s why.

In the late 1960s, a rising young singer was looking for a new stage name. Phoebe Ann Laub lacked pizzaz. She recalled the famous passenger train and so became the final incarnation of Pheobe Snow, best remembered for her 1974 hit song, “Poetry Man.”

Though, unlike her namesake, she didn’t wear all white at her concerts.

Please follow DVJournal on social media: X@DVJournal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJournal