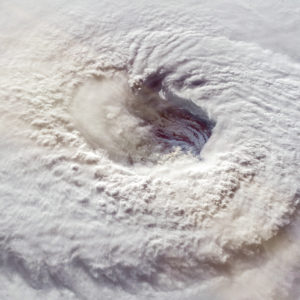

Philadelphia may not be New Orleans or the Florida coast, but it’s been hit by its fair share of hurricanes.

In October 1954, Hurricane Hazel brought 94 mph wind gusts to Philadelphia International Airport, the highest officially measured in the city. Hazel did more than $36 billion in damage and left 15 dead in the Philly region.

So when both the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and AccuWeather predict more hurricanes than usual in 2024 due to a La Nina weather pattern and warmer ocean temperatures, Delaware Valley residents should hold on to their hats.

NOAA predicts seven to 25 named storms with winds of 39 mph or higher. AccuWeather says there could be 20 to 25 named storms.

Alex DaSilva, lead hurricane expert for AccuWeather, said a high-pressure center over Bermuda usually steers hurricanes away from the mid-Atlantic region and out to sea.

“It’s very rare that you see a storm hooked back into the coast,” said DaSilva. “Obviously, it happened with Sandy.” Atlantic hurricanes are much more likely to strike Florida or the Carolinas.

But the Delaware Valley is often deluged from hurricanes that make landfall on the Gulf Coast and head north, no longer at hurricane strength but still dropping torrents of rain and spawning tornadoes, said DaSilva.

On July 8, Hurricane Beryl hit Texas as a Category 1. Then, its remnants moved toward the northeast.

Asked whether climate change is causing more hurricanes, DaSilva said meteorologists find more storms because of better technology.

“We’re going to see more storms than we did in the early 1900s,” he said. “Because we have satellites, we can find them in the middle of the ocean.” But researchers believe “there’s been more episodes of rapid intensification…We saw Beryl rapidly intensify.”

“So, in terms of the number of storms and the number of hurricanes, it’s still being debated whether there is a link between that and climate change. Some years are very active. Some are very inactive,” he said.

The deadliest hurricane in U.S. history hit Galveston, Texas. It killed 8,000 to 12,000 people, he said.

“It was in 1900, so the warnings obviously were not as good as they are today,” DaSilva said.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) helps with the impacts of hurricanes and other disasters. They drill throughout the year, a spokesperson said.

With the large number of hurricanes predicted, “it’s more important than ever to be prepared,” FEMA said. First, have multiple ways to receive alerts and warnings, including the FEMA mobile app. Know your hurricane risk and be prepared to evacuate by knowing your route.

Bryan Koon, president and CEO of IEM, a global consulting firm specializing in emergency management and disaster recovery, agrees. He strongly recommends buying flood insurance. Even if the storms don’t hit an area directly, they can “drop a prodigious amount of rain,” he said.

“Sit down with your insurance agent and review your policy,” he said. “Make sure it is what you need.”

“Flood insurance is expensive, but not having flood insurance can be way more expensive,” he said.

And history is not a guide. Hurricanes and flooding storms can hit your area. Instead, assess your house.

“When was it built? What were the building codes in place then? What happens if a storm comes through and stalls in your area and drops six, 12, or 18 inches of rain? What happens if you get sustained 100-mph winds? What if you have a tornado that shoots off one of those (hurricanes) and impacts your house?” Koon asked.

“Some simple things people can do today to improve the strength of their home,” he said. If you’re in a hurricane-prone area, “get hurricane shutters or impact-resistant windows.” Add hurricane clips to hold down your roof.

“If you’re remodeling, the prudent thing to do would be to spend some time online and look for simple ways to harden your house,” he said.

DaSilva said hurricanes are doing more damage these days because coastal areas are more densely inhabited.

“The population of South Florida has just exploded. So, I think the reason we’re seeing more damaging hurricanes essentially is–there have always been powerful hurricanes–just now, a lot of people are living on the coasts.”

Marion McFadden, the principal deputy assistant secretary for community planning and development with the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), said HUD also helps people after a hurricane or other disasters.

While FEMA and the Red Cross respond first, HUD aids residents living in housing it financed, finding new homes for them and stabilizing and repairing damaged properties.

“We take the lead for FEMA on what’s called the housing recovery and support function,” said McFadden. They work with the state, local, territory or tribal government to assess recovery needs.

But because Congress must approve HUD funding, it can take months or even years for its disaster funds to be dispersed, she said. And there are income limits to qualify. They also ensure they’re not duplicating money already provided by a homeowner’s insurance policy.

“We focus a lot on prevention and mitigation,” she said.

Please follow DVJournal on social media: X@DVJournal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJournal