(This article first appeared in Broad + Liberty)

Editor’s note: The following story has explicit descriptions of suicide and suicide attempts that may be disturbing for some readers. For anyone who is struggling with suicidal thoughts or ideations, call 988. If it is an emergency, call 911.

For any family, a suicide is a tragedy not only of the death itself, but a tragedy of unanswerable questions that gnaw and corrode.

When that suicide happens in prison, the number of those destructive questions only multiplies.

This is the life now of Janet Owens of Elverson Borough, as she seeks what answers she can gather to the death of her son, Andrew Little, who hanged himself in a prison cell at Delaware County’s George W. Hill Correctional Facility on the first Saturday in June of 2022.

“They called me on Monday and I asked [the chaplain] some questions and she said, ‘Well, I don’t know. I’ll have to get back to you.’ I asked her, ‘Was he on a mental health unit?’ ‘Oh, I don’t know.’ ‘Was he receiving treatment?’ ‘I don’t know.’”

Andrew Wesley Little was born in September of 1987. With Andrew being her second son, Janet remembers him as a much more peaceful baby than her first.

“When he turned fourteen, fifteen, when he went through puberty, that’s when his mental illness kicked in and he took off and went out [to California] and lived on the streets,” Owens said.

Eventually, Owens was able to help get Andrew enrolled in the forestry program at Penn State, Mont Alto, but Andrew’s illness came to dominate again.

Court records show Andrew had numerous contacts with various police departments in Chester, Delaware, and Philadelphia. The dockets show mental illness factored into several of those cases, such as a judge requesting a mental evaluation.

Owen’s frustrations are many, as anyone might imagine. But in particular, she feels as though many medical privacy laws, like the 1996 federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA, acted as a constant barrier between her and her sick son.

Understandably, a law like HIPAA assumes that it is meant for individual, rational actors. But Owens feels like that’s where the HIPAA and other laws like it are incomplete, and incompatible with mental illness.

“The patient has an inability to recognize their own illness. And that’s why these people think, ‘I don’t need medication.’ And part of their paranoia is they’re [thinking] ‘They’re trying to poison me. They want to give me this medication.’ and that’s why they can’t be medicated or they won’t be medicated because they don’t believe there’s anything wrong with them.”

Owens pointed out that her son’s resistance isn’t just an anecdote, it’s a diagnosis — anosognosia, when “someone is unaware of their own mental health condition or that they can’t perceive their condition accurately,” a webpage from the National Alliance on Mental Illness says.

Retired, with abundant time to just think about her departed son, she wonders how else privacy laws put a wall between her and her son.

For example, Owens says her son was in Chester County months before he was transferred to Delaware County. While there, she says he attempted suicide twice. Owens wonders if a suicide attempt is privileged medical information, and if it is, would Chester County have been prohibited from relaying this safety information to Delaware County?

She says her numerous calls over months and years to jails, prisons, hospitals, all were turned away leaving her with no way to even begin to try and help.

There are other, more straightforward questions as well.

Broad + Liberty showed Owens documents obtained from Delaware County via Pennsylvania’s Right to Know Law.

In an email from April 15, 2022, a sergeant at the GWHCF alerts several other staff members that “On unit 10, we have multiples [sic] doors issues, ranging from broken locks to doors not being able to open or only open with keys,” (emphasis added). The email went on to say that many of those same cells in the unit were frequently subjected to sewage backups.

“Every time a toilet and sink are flushed, a backup of water and sometime [sic] feces into cells and day rooms,” the sergeant wrote.

The timing of the email is important because when it was written, the government had only taken over the management of the prison from a private operator earlier that month. The email represents one of the first alerts that the new management was struggling to deal with broken locks or inoperable doors, a problem that persists to this day.

On May 4, 2022, a work order shows a repair technician worked on cell A210 to replace a wire harness on the door lock, a door lock that is meant to be operated from a remote control room.

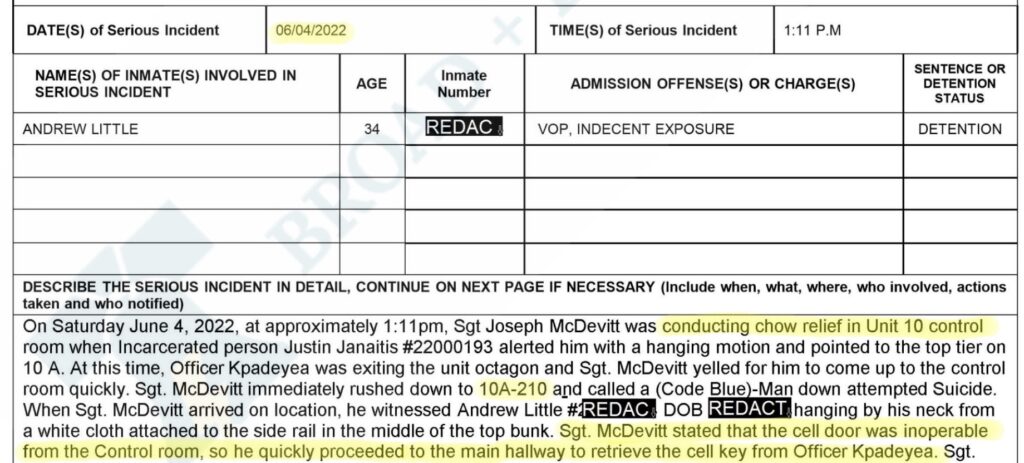

One month later in cell A210, Andrew Little hung himself apparently using sheets in the cell. But an incident report shows the door locks were still an obstacle for the officer who was rushing to help.

“Sgt. McDevitt stated that the cell door was inoperable from the Control room, so he quickly proceeded to the main hallway to retrieve the cell key from Officer Kpadeya.”

The documents stunned Owens.

“I was appalled to know that first, some of the letter from the maintenance man was saying that sewage has been seeping into these places. So is it sewage and backup that was making these [lock] systems not work? And then, if somebody should be watched regularly, what are they doing in a unit that locks and they can’t get to the locks in time? My son could still be alive, maybe.”

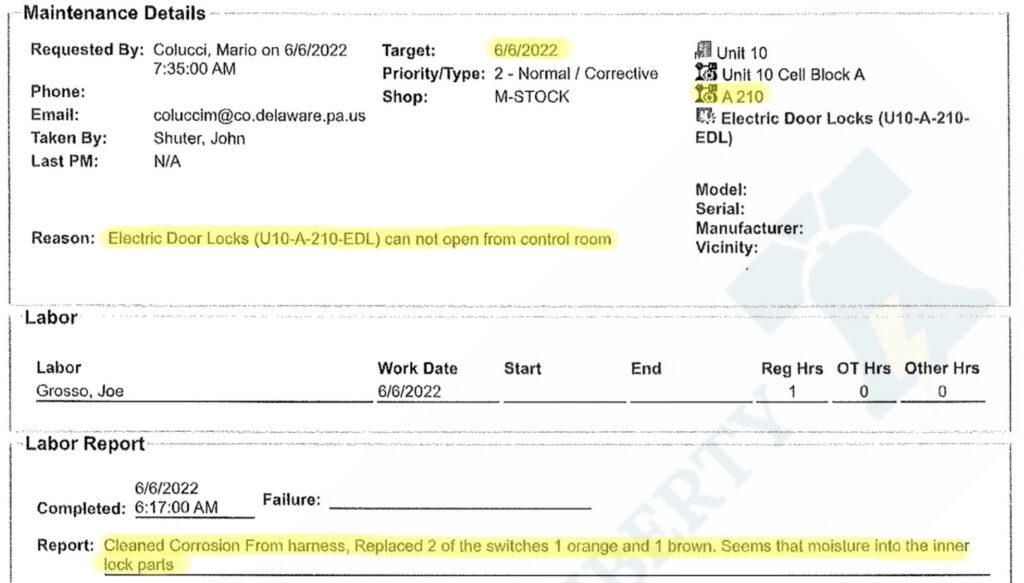

Two days after Little’s death, another work order shows the lock being fixed.

Owens’s theory about moisture is given credence when the technician noted, “Seems that moisture into the inner lock parts…” The rest of the report is obscured for some unknown reason.

Two sources with intimate knowledge of the prison say the run from Little’s cell to the control room and back for the physical keys would have taken at least two minutes, possibly as long as four minutes. Those sources have requested anonymity out of fear of career retaliation.

“He [Sgt. McDevitt] would’ve had to first run downstairs from the top tier (because that cell is on the second level), get buzzed through the 10A block door, secure that door, get buzzed out of the octagon door that connects all four blocks (A, B, C and D), get the cage door buzzed (there is a cage door that secured the control room) and finally get into the control room (which was probably already open because the officer knew he was coming). After retrieving the key you run through the same steps to get back on the unit to the cell,” one source explained.

The second source said other details in the incident report are telling. The report begins by noting that the officer who first became aware of the situation “was conducting chow relief on Unit 10[.]”

“The fact that the Sgt. is ‘conducting chow relief on Unit 10 control room’ is a very clear indicator that the unit was short staffed,” the second source said. “Essentially, the Sergeant had to step in as the Control Room Officer to allow another officer to take a lunch break. The report only mentions one other officer being present at the time of the incident. The information suggests that there was one Control Room Officer and one Block Officer left responsible for a unit that is supposed to have the highest level of security. If the unit were fully staffed it would consist of six total officers.”

The first source confirmed the concern about staffing levels, saying, “At the time of the incident only one officer was assigned to that block.”

The county declined to comment on several questions posed by Broad + Liberty, some of which were not specific to Little’s death.

Owens said she has already been working with local attorneys on a wrongful death lawsuit, prior to seeing the documents provided by Broad + Liberty. While no suit has been filed yet, should it be successful, she hopes to use any monetary awards to work on mental health issues.

“He [Andrew] shouldn’t have been in prison. He should have been in a mental health institute. And because there’s nowhere to go, that’s where he was. And if that’s what they’re going to do, then they need to protect these people, these kids, these children, these young men that should be getting care outside, but they don’t have anymore. And they closed them down. They closed down Brandywine. It was the last one here. He was in Belmont. He was in Brandywine. I can’t even tell you how many places he was.”

The incident makes clear Andrew was in Delaware County’s custody because of a parole violation related to an indecent exposure charge. None of the court dockets available on Pennsylvania’s Unified Judicial System website for Delaware County show charges for indecent exposure. But Owens says her son shouldn’t be thought of as a sexual offender, rather that he was mentally ill and had lost all sense of right and wrong. Supporting that idea is the fact that all of the dockets that are available from Delaware and Chester counties are for nonsexual offenses like disorderly conduct, trespassing, shoplifting, or simple assault.

Owens is estranged from her former husband, and Broad + Liberty was not able to find contact information for Little’s father.

Broad + Liberty has been able to get some answers for Owens. Her son was being housed in the mental health wing according to prison sources who spoke with Broad + Liberty. However, our inquiries did not get any kind of answer as to whether Little and other mentally ill patients were being checked on regularly.

As for whether HIPAA could have acted as a barrier between Little’s time in Chester County versus Delaware, Chester County spokeswoman Rebecca Brain responded to a hypothetical question about inmate privacy that essentially mirrored Little’s situation.

Brain first explained that the county contracts with Primecare for its delivery of medical care for the county’s correctional facility.

“If that inmate is then transferred to another correctional facility that also contracts with Primecare as its medical provider, that information is shared across Primecare’s medical record platform. If the correctional facility does not use Primecare as their medical provider, then Primecare, when aware of a transfer, drafts and sends a document with the patient/transporting authority which includes information regarding the inmate’s suicidal ideology and other basic medical information,” Brain explained.

“According to Primecare, this process falls under continuity of care, where no authorizations are required for the sharing of information between facilities. I would recommend reaching out to Primecare, as they are contracted as the medical provider for a number of prisons and could provide you with more information,” she said.

While this answers some questions, it raises others, such as whether one prison would be able to alert another about known suicide risks even if there were no direct transfer of the inmate, as is used in the hypothetical.

With reform in mind, Owens says she has been following changes in California led by Democrat Gov. Gavin Newsom.

“Governor Gavin Newsom’s Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment (CARE) Court initiative would grant more authority to a civil court judge to mandate treatment,” a 2022 report from a CBS affiliate in San Francisco said. “Disability rights groups say that’s a violation of civil liberty. But some family members of the severely mentally ill say it may be the only way for them to survive.”

Delaware County’s prison had been privately managed for nearly 30 years until 2022. Although the formal transition to government management did not take place until April 2022, the county’s hand-picked warden, Laura Williams, started in February.

In the 23 months since then, the GWHCF has witnessed eleven deaths, four of them suicides.