A common question is repeated these days from Alaska to Maine: What will we do with the leftover turkey? It’s as much a part of the holiday tradition as the dressing and pumpkin pie.

There are always the usual options. Turkey casserole, turkey hash, turkey noodle soup, turkey tetrazzini, and, of course, that old, reliable standby, a cold turkey sandwich.

A company had the same problem on its hands in 1953, only on a scale infinitely larger than your refrigerator. And what it did with all that leftover bird created an American classic. But let’s start a little before that.

The frozen food business was on a roll throughout the middle of the 20th century. Clarence Birdseye discovered how to flash-freeze fish in 1929, creating a new industry. By 1945, Maxson Food Systems sold complete frozen meals to the military and commercial airlines. In 1949, the first frozen dinners appeared in the Pittsburgh area, packaged in paperboard containers. They expanded to much of the East Coast three years later.

In 1950, Nebraska-based C.A. Swanson began selling oven-ready pot pies and turkeys. Business was brisk. Then, in 1953, someone in the company goofed. Badly. The supply of frozen turkeys it had produced far exceeded the demand. Swanson was stuck with 260 tons of it in 10 refrigerated railroad cars. And get this: The cooling system worked only when those cars were moving, meaning Swanson had to keep the cars traveling to keep the turkey from going bad. A solution was needed, and it was needed ASAP.

Necessity, they say, is the mother of invention. The answer came from a company salesman.

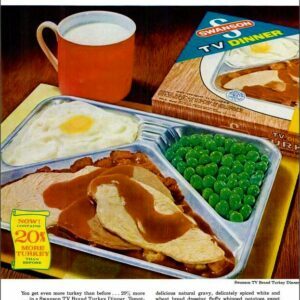

Gerry Thomas had tried frozen dinners on airline flights the year before and was impressed by them. He immediately rolled into action, ordering aluminum trays similar to those used on airplanes (and based on trays the military had used in World War II). He filled them with sliced frozen turkey, cornbread dressing with gravy, and peas.

The concept was astonishingly simple. Housewives popped them into the oven, waited 25 minutes, and then — presto! — dinner was served. All for 98 cents each. (Though that wasn’t the bargain it sounds like today. It was pricey in 1953. That 98 cents is about $11.40 today.)

We don’t know who came up with “TV dinners.” There’s a widely believed misconception that the new product was intended to be eaten while watching television. Not true. The new medium was all the rage in 1953, so Swanson piggybacked it by slapping “TV” on the box.

(It’s a tried-and-true marketing gimmick. Consider the Charleston Chew candy bar. Many folks mistakenly presume it originated in Charleston, S.C. In fact, when a Massachusetts candymaker began producing it in the 1920s, the Charleston dance craze was in full swing. Hence the sweet treat’s name.)

Back to the TV dinner. Swanson rolled out 5,000 of its new frozen meals. Company executives held their breath. Would American consumers like it? They didn’t have to wait long for the answer.

The TV dinner was an instant hit. The first 5,000 meals sold out almost immediately. It turned out that busy moms were willing to pay for the convenience of quickly and easily feeding their hungry young Baby Boomer kids.

That original turkey overrun in ’53 turned out to have been a very lucrative mistake. Another round of TV dinners was immediately ordered. It, too, sold exceptionally well. By 1954, 10 million units had been bought. Business was so good Swanson gave up its profitable butter and margarine line to focus on the new product. The company expanded to 20 plants with a combined workforce of 4,000 to keep pace with the demand.

The original TV dinners are still around, though microwave food has greatly diminished its market share. It’s estimated that 127.9 million of them were consumed in 2020; it’s projected to jump to 130.5 million next year.

Not bad for a product that all started with 260 tons of leftover turkey. It makes that half a bird still lingering in your fridge look puny in comparison, doesn’t it?