Face it: Bureaucrats, those unelected holders of colorless government jobs, are among the least popular Americans. They rate at the bottom of the list alongside lawyers, used car salesmen, and the guy who keeps calling about your car’s extended warranty.

Yet we all owe a huge debt to one such federal drone who, when a crisis came, acted calmly, cooly, and saved the greatest documents in our history. This is his story.

Secretary of State James Monroe stood on a Maryland bluff one Saturday morning in August 1814. Through shimmering heat, he watched America’s nightmare come to life as British warships sailed up the Patuxent River and unloaded hundreds of despised Redcoats. The following Monday he sent an urgent message to President James Madison: “…the enemy are in full march on Washington.”

Monroe dashed off a second dispatch to State Department clerk Stephen Pleasanton instructing him to take “the best care of the books and papers in the office.”

Pleasanton knew exactly what his boss meant. The State Department held the country’s most precious documents. The original U.S. Constitution, George Washington’s personal letters, journals of the young Congress, and much more.

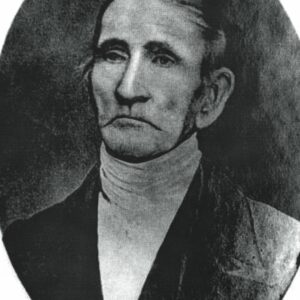

Pleasanton was 38 at the time, a native of Delaware, slow and methodical and plodding – the ideal government bureaucrat. Yet when faced with the challenge of a lifetime he was up to the task.

Panic was all around him. The feared British troops had initially approached Washington, then disappeared. Now they were suddenly back and heading straight for the capital.

Pleasanton bought all the linen he could lay his hands on, rounded up every government employee in sight, and ordered them to start sewing sacks.

Just then Secretary of War John Armstrong strolled in. (The State Department was housed in the War Department building back then.) Seeing what was going on, he harshly jumped Pleasanton’s case, accusing him of spreading a false alarm and making the city’s mayhem even worse.

Bureaucrats are experts in ignoring what other people say. Pleasanton put that skill to good use by continuing with his task, replying that prudence demanded the precious papers be evacuated. Armstrong stomped off in a huff.

Pleasanton rounded up 22 carts and filled them. Incredibly, as he was preparing to leave the office, he noticed the original Declaration of Independence hanging on the wall. The last thing he did before fleeing was to remove it from its frame, roll it up, and put it in a cart with all the other valuables.

Then it was a long, slow trudge to safety in Leesburg, Virginia some 50 miles away. Once there, the most important of the papers were locked inside the safe of Rev. John Littlejohn, Leesburg’s internal revenue agent. Pleasanton staggered to a local inn and dropped into a bed utterly exhausted. Only then, with his mission accomplished, did he allow himself to sleep.

He awoke to disturbing news the next morning. A massive blaze had lit the eastern sky in the direction of Washington the night before. All too soon, the worst was confirmed. The White House, the Capitol, and even the War Department building that Pleasanton had just evacuated were now smoldering ruins. He had saved our nation’s priceless heritage in the nick of time. Although much of the capital was gone, thanks to Pleasanton’s quick actions the young nation’s founding documents still existed.

Then it was back to the bureaucratic salt mines. In 1820, Pleasanton was appointed head of the government’s Lighthouse Establishment. For decades, he pushed paperwork regulating the beacons that guided international trade safely into America’s ports and harbors.

Stephen Pleasanton died at age 78 in 1855. He rests today in Washington’s old Congressional Cemetery where the modest bleached headstone atop his grave says nothing about his remarkable heroism in 1814.

Please follow DVJournal on social media: Twitter@DVJournal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJournal