For another point of view see “Counterpoint: What Would Founders Think of Dobbs Decision? Not Much”

When the U.S. Constitution was ratified June 21, 1788, the two men most responsible for its success were Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, who, along with John Jay, wrote “The Federalist Papers.”

Four years later, they had markedly different approaches to interpreting the document they helped create.

Hamilton, perhaps because he wanted a national bank that wasn’t mentioned in the Constitution along with an active central government, came to interpret the Constitution as being open-ended: if something isn’t prohibited by the document, it is allowed — or as he and his Federalist friends might have put it, implied.

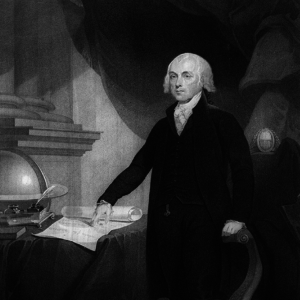

By contrast, the Father of the Constitution, James Madison, along with friends like Thomas Jefferson, viewed the Constitution as a limiting document: if something is not expressly stated in the Constitution, it is prohibited.

More than two centuries later, the debate between Hamilton and Madison continues to define the two opposing schools of constitutional interpretation. As of June 24, 2022, when the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision was published and Roe v. Wade was overturned, it’s clear Madison won.

One of those schools, and the one that prevailed in the Dobbs decision, is referred to as textualism or, as it is sometimes called, originalism. Madison would have argued for textualism/originalism by describing what we usually do when we look at words and try to figure out their meaning. The textualist/originalist approach first asks judges to apply the text — do what the words say. But it recognizes words can be unclear when applied to varying circumstances. In that event, the originalism part of the approach says to look beyond the words but only to ask what was intended by those who chose — and those who ratified — those words. They can tell you what they meant.

The second school of constitutional interpretation, the Hamilton method, goes beyond limiting rights to what was said and what was intended. This approach, which could be called the Humpty Dumpty school of constitutional interpretation, was best expressed by Humpty himself. You will recall Alice asked him in “Alice in Wonderland” “whether you can make words mean so many different things.” Humpty’s response was that words were not his master. Instead, he said that when he uses a word “it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.”

Now it was conceded by Justice Harry Blackmun in his majority opinion in Roe v. Wade that there were no constitutional words expressly conveying a right to abortion or even any suggestion of an original intent to convey such a right. But, the words were not going to be his master. Instead, he agreed with Humpty Dumpty that it was permissible to shift meanings and invent a constitutional right to an abortion. The lack of an expressed instructional prohibition on abortions was claimed in Roe to permit the finding of a constitutional right to abortion.

It was the Humpty Dumpty logic of Roe v. Wade that led the majority in Dobbs to decide that the question of abortion in our country had a great fall and could not be put together again. Instead, the Dobbs court, recognizing the lack of a constitutional basis for the Roe decision, returned the issue of abortion to the state for legislative resolution.

The Dobbs majority said legislators have to put this together. James Madison would have approved.

Please follow DVJournal on social media: Twitter@DVJournal or Facebook.com/DelawareValleyJournal