Even as more and more people receive the COVID-19 vaccine, some remain afraid to leave their homes. This condition is quickly earning the nickname “Pandemic PTSD.” But is that a correct assumption?

Dr. Thea Gallagher from Penn Medicine sat down with Delaware Valley Journal to discuss it.

Last year government shutdowns in reaction to COVID-19 thrust Americans into a sheltered, homebound life. When it first broke out, there was a lot of fear of the unknown and speculation about the long-term impact of the virus, although many Americans believed it wasn’t real or that it would disappear after a few months.

Unfortunately, when the entire world collectively locked down, COVID fears expanded. The global COVID-19 death toll has risen to more than 3 million. And that knowledge has taken an emotional toll on people around the world. Although vaccines are becoming readily accessible to almost everyone in America, there’s still a level of anxiety for many people when it comes to leaving their homes.

Studies have shown that people have a varying degree of PTSD symptoms in different parts of the globe. While it’s true that heightened cases of anxiety and depression have increased due to the pandemic, statistically there isn’t enough data yet to confirm pandemic-related PTSD. However, the few studies that have been published show that those with high exposure to the virus are more likely to develop PTSD or other anxiety-related disorders, especially individuals who watched family members suffer from the virus.

A study of nurses in China revealed that about 17 percent experienced some form of PTSD symptoms. In another study of 7,000 China citizens, 35.1 percent of them reported some form of anxiety symptoms, while others experienced depression and poor sleep quality.

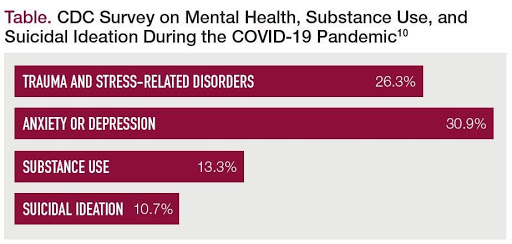

In a US web-based survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control, it was shown that 26 percent of patients had trauma or stress-related disorders — such as PTSD — related to the pandemic. However, 31 percent reported having feelings of anxiety or depression. Another 13 percent used substances to cope with the pandemic. And an additional 11 percent considered suicide due to the stress of the situation.

Coining the term “pandemic PTSD” for this condition might be a little premature, based on what Gallagher said.

“For something to be classified as PTSD, there needs to be a trauma,” Gallagher said. While there certainly are people who will develop PTSD from this pandemic, that isn’t going to be the case for everyone. Gallagher mentioned a very real chance for those who have suffered the loss of a loved one or the doctors and nurses working in intensive care units which have seen so much death due to the virus to develop PTSD.

However, rather than traditional PTSD, a lot of psychologists are talking about re-entry anxiety.

“You’re afraid to go back into the world,” Gallagher said. “We have to identify what people are afraid of.” Are they afraid of COVID? Gallagher thinks a lot of people who had clinical or subclinical social anxiety disorder have become more isolated and believes it’s important to identify what people actually fear.

As we slipped deeper into the pandemic across the world, the restrictions, such as mask-wearing and social distancing, easily made a person feel less human. Going so long without having those physical connections to other people can make re-entering society difficult.

“For a lot of people, they’ve been so out of practice that another huge change feels really overwhelming,” Gallagher said.

It’s essential that people who have suffered from depression and anxiety before the pandemic seek help from an exposure therapist if they are still afraid to leave their homes.

“We know that people’s mental health has been hit pretty hard,” Gallagher said. “You know, depression and anxiety, we know it’s increased, so [Gallagher] wouldn’t be surprised if we’re going to see that it’s pretty difficult for some people to re-emerge into normal life. It’s hit everyone differently, and some are more severe than others.”

However, with the rollout of the vaccines, there is hope.

“The data on vaccines and the deaths as a result of vaccinations is really promising,” Gallagher said, indicating that the goal is herd immunity. “We haven’t been thriving. We’ve been surviving. We can’t go on vacation. We can’t go out to dinner. We can’t go see our friends. We can’t do normal things that make us human, and over time that takes a toll.”

When asked what sort of treatment she would recommend for people still afraid to leave their homes — even with mass vaccinations, Gallagher said, “If you haven’t [physically] seen anyone for an entire year, you probably need a therapist to help you get to that point.”

If you have a loved one struggling with the anxiety of leaving their homes, the best thing you can do is create a safe space, be there for them and ask anxiety sufferers what you can do to help, she added.

If you’re someone suffering from re-entry anxiety, Gallagher suggested, “If you’re not at a severe level, try to push yourself.” It’s all about getting ourselves back to a sense of normal, even if it is a modified version of what it used to be.

“At some point, you have to start doing, and that can be the really difficult part. Medication can maybe help you get to that part to start the doing, but at some point, you’re going to have to do the doing,” she said.