When it comes to COVID testing, Pennsylvania is next to last among nearby states, a new Delaware Valley Journal analysis found.

Pennsylvania in many ways is located at an American crossroads: It’s a northeastern state that reaches into the Great Lakes region, embraces part of Appalachia, and nearly touches the border of the old Confederacy. And so Delaware Valley Journal analyzed 10 months of data compiled by The COVID Tracking project from 17 states across these regions looking as far north as Maine, south as North Carolina, and west to Indiana.

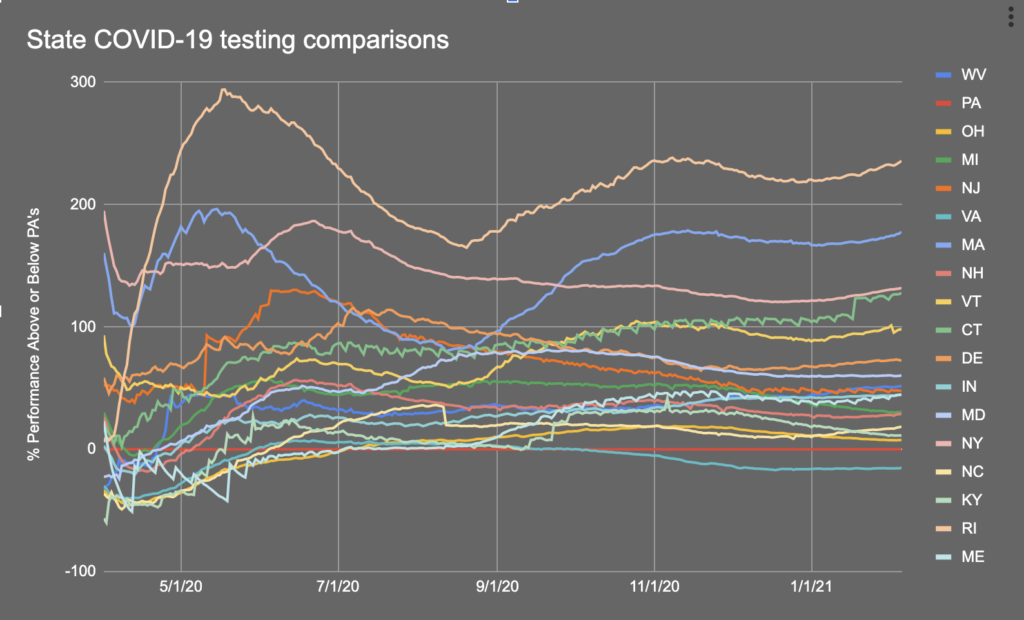

The result: Pennsylvania’s cumulative testing numbers are worse than every other state except Virginia.

Using per-capita adjusted numbers, some states like Rhode Island and New York have essentially doubled Pennsylvania’s performance testing their populations, and they’ve done so consistently over the course of several months. New Jersey has tested its citizens at a 50 percent faster clip than the Keystone State for nearly the length of the pandemic.

Many health experts are concerned that testing capacities still are not where they need to be nationwide to help prevent more outbreaks of the virus. Those worries come at a time when vaccine messaging has begun to absorb most of the communications energy and effort. And those worries are tied to increasing reports that new strains of the virus are gaining momentum.

The above graph displays how other states compared to Pennsylvania’s COVID-19 testing, which is shown as an unvarying red line across the X-axis. For example, Connecticut, shown in dull green, started off April on nearly the same footing as Pennsylvania, but by February was consistently doubling Pennsylvania’s efforts.

The DVJ analysis closely tracks data published by Johns Hopkins University. But whereas the Johns Hopkins data only show a daily snapshot, the DVJ analysis goes back to the beginning of April, and concludes with data available up to Feb. 5.

Pennsylvania PIRG, a public health advocacy organization, recently issued letter grades on testing capacity. It gave the commonwealth an F, while New Jersey scored an A+.

Matthew Wellington is the public health campaigns director for Pennsylvania PIRG and says the most important factor that could move the needle would be federal dollars.

“We need the federal government to give states like Pennsylvania more federal support, and that means more money for ramping up testing infrastructure, more coordination, across the board,” Wellington told Delaware Valley Journal. “And that, I think, is recommendation number one.”

It’s a common refrain, but not one backed by the data — at least when comparing one state to another. The other states in the region have received a similar proportion of federal help as Pennsylvania, and yet they’ve been able to use the same funding to consistently outperform the Keystone State.

On that point, Wellington agreed some issues don’t come down to money or labs, but instead are dependent on communication and execution of strategy, pointing to instructional websites as an example.

“New Jersey’s website is incredibly clear who should be getting a test and how you should get one. It literally says testing is available to anyone in New Jersey. It’s all right there, it’s simple information, it’s accessible. Pennsylvania’s website is not.

“If you look at Pennsylvania’s website, it’s broken down into four different tiers with all kinds of information in there. This should be as simple as possible. When you’re communicating with the public, you want people to understand that COVID testing is not some scarce resource that we’re still holding on to only for absolute emergencies. People should be able to go and get tested regularly because that’s what it’s going to take to really rein in this virus.”

In their defense, a Department of Health spokeswoman argued the data compiled by The COVID Tracking project — the same source data Delaware Valley Journal used for this analysis — may not be the ideal measuring stick.

“As you are looking at the COVID Tracking Project, it is important to note that the numbers they are showcasing here seems to not include the antigen tests, which Pennsylvania has received over 1.4 million tests for since May 2020,” DOH spokeswoman Maggi Barton told DVJ.

The testing tracker provided by Johns Hopkins University specifically advises against using antibody or serology tests when gauging a state’s total testing performance.

“When states report testing numbers for COVID-19 infection, they should not include serology or antibody tests,” the Johns Hopkins website says. “Antibody tests are not used to diagnose active COVID-19 infection and they do not provide insights into the number of cases of COVID-19 diagnosed or whether viral testing is sufficient to find infections that are occurring within each state. States that include serology tests within their overall COVID-19 testing numbers are misrepresenting their testing capacity and the extent to which they are working to identify COVID-19 infections within their communities.”

The DOH points to a number of accomplishments it says show a robust response.

“Through our advanced testing strategy, we set a goal of testing at least 2 percent of the population each month and surpassed that goal each time. In fact, we are now at roughly 37 percent of the state’s population,” Barton said.

Because the Department offered a lengthy response of its work on testing, DVJ is publishing that portion of the response, in full:

The Department of Health’s State Laboratory testing capacity has increased dramatically from being able to conduct up to four diagnostic tests per day in February to approximately 1,200 tests per day in July. As of January 2021, the state laboratory has tested over 155,000 specimens in total for COVID-19.

- The Pennsylvania Department of Health and the Pennsylvania Department of Community Economic and Development (DCED) partnered with Eurofins to assist with testing specimens from skilled nursing facilities statewide at no cost to facilities. Providing this support enabled all long-term care facilities to complete their universal testing.

- The Pennsylvania Department of Health and Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency (PEMA) partnered with CVS Health to offer COVID-19 testing services to skilled nursing facilities statewide, free of charge. Again, providing this support enabled all long-term care facilities to complete their universal testing.

- The department partnered with Latino Connection, a marketing and communications agency to bring COVID-19 testing to more communities. Known as CATE, Community-Accessible Testing & Education, the unit is equipped to conduct COVID-19 testing on-site through a mobile RV vehicle while also educating the public on how to stay safe and healthy. The mobile response unit’s tagline is “Sharing knowledge to erase fear,” which it did through widespread community healthcare and health education offered with no insurance required. CATE toured minority, Spanish-speaking, and underserved communities throughout Pennsylvania in fall 2020. It tested over 4,000 people through the Latino Connection events. Latino Connection also has another mobile testing unit, Cora, which is short for Corazón, the Spanish translation of heart. Cora also traveled the commonwealth to bring COVID-19 testing into more underserved communities in summer 2020.

- The Pennsylvania Department of Health worked with Quest Diagnostics and Walmart to provide drive-thru testing sites for residents living in areas with limited access. It tested almost 5,000 people through its Walmart locations.

- The Wolf Administration expanded its partnership with AMI to increase testing opportunities across the state in the 61 counties where the department has jurisdiction after completing its first round of testing clinics. It tested over 57,000 people through the AMI testing sites since September 25, 2020.

Even as so much focus has shifted to how the many COVID-19 vaccines may be able to offer the beginning of a return to some kind of normal, Wellington says aggressive testing will still be an important part of the overall toolkit to reach that goal.

“How much testing is the state doing versus how much testing does a state have to do to suppress the virus? That’s what we look at,” Wellington said. “And when you compare the amount of testing that Pennsylvania is doing to how much it needs to do to suppress the virus, it’s still well below that level.”